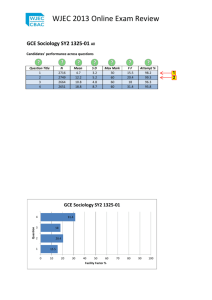

the study - Utah Criminal Justice Center

advertisement