Effective Approaches to Leadership Development

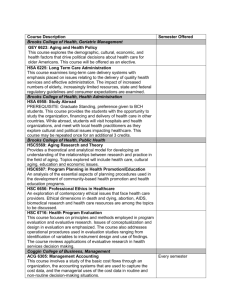

advertisement