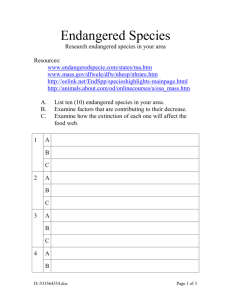

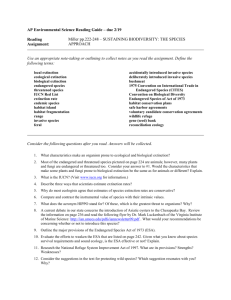

The Endangered Species Act: A Primer

advertisement