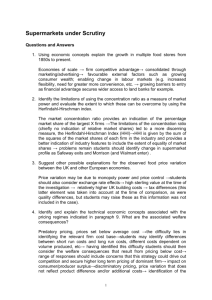

competition inquiries into the groceries market

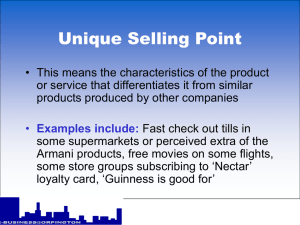

advertisement