Objects Suspended in Light - Thomas

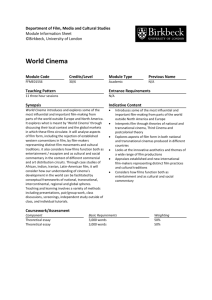

advertisement