Assessment - Ohio Speech-Language

advertisement

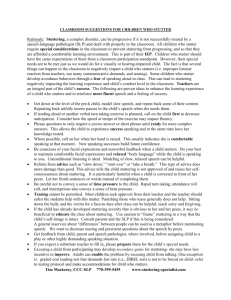

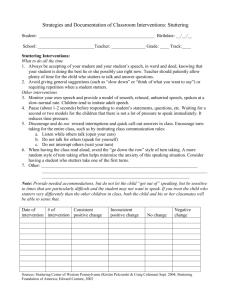

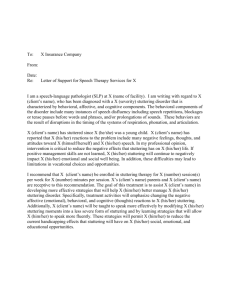

2/4/14 Disclosure Update in Fluency: • I receive no financial or non-­‐financial gain by discussing any products or programs in this workshop. What Clinicians Need to Know Lonnie G. Harris, Ph.D., CCC-­‐SLP Lonnie.Harris@ebshealthcare.com 2 Topics Covered Topics Covered Assessment Treatment • General Assessment Guidelines • Contextual vs. Noncontextual Speech • The Fluency Protocol • General Treatment Guidelines • The Fluency Matrix • Treatment Techniques • The Teacher/Parent Interview • Fluency Shaping • The Fluency Assessment Summary • Reducing Shame and Avoidance • Stuttering Modification • Generalization • Educational Relevance 3 • Determining if Progress is Being Made 4 Assessment General Guidelines Assessment: 1. Obtain a speech sample that is as representative as possible of the child’s speech in everyday use. General Guidelines 2. Obtain a sample of the child’s speech under circumstances that are constant from one child to the next. 5 6 2/4/14 Assessment Assessment 3. Generate, from obtained speech samples and incidental observations, quantitative and qualitative descriptions of the child’s fluent and disfluent speech behaviors that can be related to vocal tract physiology. 5. Obtain information about a child’s early social, physical, behavioral, and speech development, including information about variables that might be related to the origin of the disorder or its course of development, and apply this information to treatment planning. General Guidelines 4. Obtain information about variables that affect the child’s fluency level and apply this to treatment planning. General Guidelines 7 8 Assessment Assessment 6. Obtain information about variables that might influence clinical outcome and/or the prognosis for treatment and apply this to treatment planning. 8. Generate descriptions of the results of assessment that are communicable to other professionals and lay persons. General Guidelines General Guidelines 7. Obtain information about other communicative problems or disorders that may or may not be related to fluency. 9 10 Assessment Protocol – Type of disfluency Assessment: The Fluency Protocol 11 Interjections Hesitations Whole-­‐word reps Co-­‐existing struggle Part-­‐word reps Prolongations I-­‐uh-­‐want to go. I want-­‐want-­‐want to go. I want to g-­‐g-­‐g-­‐go. I want to gggggo. 12 2/4/14 Assessment Assessment Protocol – Size of speech unit affected Sentence Phrase Word Syllable Sound Protocol – Frequency of repetitions I want to go – I want to go. I want – I want-­‐ I want to go. < 2% 2% to 5% > 5% I want-­‐want-­‐want to go. I want to g-­‐g-­‐g-­‐go. I want to gggggo. Repetition count includes all types, from sentence reps to sound repetitions. We are calculating the percentage of repetitions in overall speech 13 Assessment Assessment Protocol – Frequency of prolongations < 1% 1% or greater 14 Protocol – Frequency of overall disfluencies Because prolongations are NOT heard in typically-­‐ developing children, they are considered abnormal if produced in more than 1% of speech. < 5% 5% to 10% > 10% We are calculating all types of disfluencies in overall speech 15 Assessment Assessment Protocol – Typical reiterations per repetition < 2 2 – 5 > 5 16 Protocol – Average duration of prolongations I -­‐ I want to go. < 1 second 1 second I – I – I – I to go. I – I – I – I – I – I – I want to go. 17 I wwwant to go. I wwwwwwwwwwant to go. Again, prolongations are NOT heard in typically-­‐developing children. 18 2/4/14 Assessment Assessment Protocol – Audible effort None observed Hard glottal attacks Vocal tension Disrupted airflow Pitch rise Other abnormalities Protocol – Rhythm/tempo/speed Because audible effort is NOT noted in typically-­‐developing children, it is considered abnormal if observed at all. Slow / normal Evenly Paced Fast Irregular 19 Assessment Protocol – Audible learned behaviors ta-­‐ta-­‐table tuh-­‐tuh-­‐table Schwa replacements are NOT heard in typically-­‐developing children. 20 Assessment Protocol – Schwa replacement Not observed Observed Don’t confuse a rapid rate with cluttering, which has a completely different diagnostic protocol. 21 Not observed Circumlocations Avoidance tactics Starters Assessment Assessment Not observed Facial grimacing Head movements Body involvement Score of 14-­‐20 Score of 21 or greater Protocol – Visual evidence Audible behaviors are NOT heard in typically-­‐developing children. 22 Protocol – Score interpretation Visual behaviors are NOT heard in typically-­‐developing children. 23 24 2/4/14 Assessment Fluency Matrix Assessment: • Frequency of dysfluencies The Fluency Matrix • Type(s) of dysfluencies • Phonatory arrests & sustained articulatory postures • Speech sound prolongations 25 • Schwa replacement 26 Assessment Fluency Matrix Assessment: • Physical concomitants The Teacher/Parent Interview • Awareness and emotional reactions • Avoidance behaviors and peer reactions • Adverse effect on educational performance • Fluency rating 28 27 Assessment Teacher/Parent Interview Assessment: • Interpret results from each interview. The Fluency Assessment Summary • Score Teacher Interview on the Fluency Matrix under “Adverse Effect.” • Parent Interview results only get entered on the Fluency Matrix if the child is a preschooler and there is no teacher to document adverse effect. 29 30 2/4/14 Assessment Fluency Assessment Summary Educational Relevance • Behavioral components • These components comprise observed stuttered behaviors • Physical concomitants are included in this section. • Affective components • Student’s awareness to his/her stuttering • Student’s reaction to his/her stuttering • Cognitive components • Avoidance behaviors • Peer reactions to student’s stuttering 32 31 Educational Relevance • Educationally Relevant is a phrase that comes from IDEA 1997 and has been interpreted in many different ways, most of which do not accurately reflect the intent of the law. • The term means that goals must address areas of importance in the academic setting. This does not mean, however, that goals must focus solely on academic issues. Treatment: Contextual vs. Noncontextual Speech 33 34 Treatent Contextual vs. Noncontextual Speech General Treatment Guidelines Contextual Naming objects Short Phrase response Telling a story about a picture Rela;ng informa;on Answering ques;ons Giving instruc;ons 35 Noncontextual 36 2/4/14 Treatment Guidelines Treatment Guidelines 1. Reduce the frequency of stuttered behaviors without increasing the use of other behaviors that are not part of normal speech production. Fluency Shaping 2. Reduce the severity, duration, and abnormality of stuttering behaviors until they are (or resemble) normal speech discontinuities. Stuttering Modification § § § § § § § Reduced speech rate (if rate is an issue) Easy onset of voicing (“easy speech”) Reduced articulatory pressure (light contacts) Continuous phonation Slightly stretching first sound Confidential voice GILCU/ELU § Cancellation (post-­‐block modification) § Pull-­‐out (within-­‐block modification) § Preparatory set (pre-­‐block modification) 37 38 Treatment Guidelines Treatment Guidelines 3. Reduce use of defensive behaviors. 6. Increase the frequency of social activity and speaking. 4. Remove or reduce processes that create, exacerbate, or maintain stuttering behaviors. 7. Reduce attitudes, beliefs, and thought processes that interfere with fluent speech productions or that hinder the achievement of other treatment goals. 5. Help the person who stutters make treatment decisions about how to handle speech and social situations in everyday living. 39 40 Treatment Guidelines Treatment Guidelines 8. Reduce emotional reactions to specific stimuli when these have a negative impact on stuttering behavior or on attempts to modify stuttering behavior. 9. Seek helpful combinations and sequences of treatments, including referral, for problems other than stuttering that may accompany the fluency disorder, such as cluttering, learning disability, language or phonological disorder, voice disorder, psychoemotional disturbance. 41 42 2/4/14 Treatment Guidelines 10. Provide information and guidance to clients, families, and other significant persons about the nature of stuttering, normal fluency, and the course of treatment and prognosis for recovery. Therapy Techniques 43 44 Therapy Techniques Fluency Shaping • There are numerous techniques to help people speak more fluently, such as easy starts, light contact, continuous phonation, altered pausing and phrasing, etc. We can simplify this by recognizing that all these techniques are actually based on changing one of just TWO fundamental parameters of speech. • Timing changes are included in techniques such as (slow) prolonged speech, slight breathiness, pausing, phrasing, and continuous phonation. • The sheer number of techniques is a source of confusion for people who stutter and their SLPs. • How do we know if we’re using the right technique? • Tension changes are included in techniques such as light contact and easy starts. 45 46 Fluency Shaping Fluency Shaping • Why timing and tension? • All techniques to enhance fluency involve changes to the speaker’s regular speech pattern. • Because these are two aspects of speech production that are disrupted during moments of stuttering. • The speaker’s regular speech pattern is disrupted by involuntary feelings of loss of control and associated reactions that we call the surface behavior of stuttering. • Speech techniques involve replacing disrupted timing and tension with modified timing and tension. • Compare to driving • Compare to ice skating • Techniques do not fix the problem – they compensate for it. 47 48 2/4/14 Fluency Shaping Stuttering Modification • All techniques to enhance fluency involve changes to the speaker’s regular speech pattern. • Recognizing that there is no cure for stuttering, we must come to terms with the fact that our clients will continue to stutter (in some fashion). • Speech techniques can help prevent moments of loss of control or reduce the severity of the reaction, but they require effort each and every time they are used. • Of course, we will definitely help our clients learn strategies that reduce the frequency of stuttering. • The more the speaker wants to modify speech, the more effort he needs to exert. • Still, some stuttering will remain. 49 Stuttering Modification 50 Stuttering Modification What form will that remaining stuttering take? What am I doing when I stutter? • People who stutter are aware, at some level, of the various speech and non-­‐speech behaviors they exhibit during moments of stuttering. • Will it be tense or disruptive to communication? • Can the speaker learn to stutter in a way that is less tense and less disruptive to communication? • Step 1 in therapy is to help speakers learn more about stuttering. 51 Stuttering Modification 52 Stuttering Modification Learning About Stuttering Many ways to learn about stuttering The goal here for speakers to be able to produce instances of stuttering (fake or real) and describe what they do with their speech mechanism during stuttered (and fluent) speech. • Reading about stuttering and the experiences of others who stutter. • Talking to other people who stutter (self-­‐ help groups) and observing their stuttering. 53 54 2/4/14 Stuttering Modification Stuttering Modification Learning About Stuttering Learning About Stuttering What people “do” during stuttering What people “do” during stuttering • Increase tension in their speech muscles • Move their arms or legs • Increase physical tension in muscles elsewhere in the body • Tense up in anticipation of producing certain sounds or words • Hold their breath • Pretend to forget what they are saying • Expel all the air in their lungs • Blink their eyes, turn their heads 55 • Cough, clear their throat, look away, to postpone speaking until they are ready • Avoid talking altogether Stuttering Modification Stuttering Modification • As speakers begin to understand more about what they do during moments of stuttering, they become ready to try to change what they are doing. • To make it easier, speakers can try to “hold on” to a moment of stuttering (“freeze”), then gradually try to increase or, ultimately, decrease the tension in their muscles. Changing Stuttering Changing Stuttering • Initially, this will be very difficult. • Remember that these speech patterns have been built up for over a long period of time and are often “entrenched.” 56 • The goal here is to learn to stutter more easily. 57 58 Stuttering Modification Stuttering Modification • Exercises that help speakers learn to “stutter more easily”: • Exercises that help speakers learn to “stutter more easily”: Changing Stuttering Changing Stuttering • Increasing, then decreasing physical tension in various parts of the body, ultimately including the speech mechanism • This “negative practice” exercise forms the building blocks for Van Riper’s cancellation technique. • Pseudostuttering using a high degree of physical tension, followed by a lower degree of physical tension • Using “easy” pseudostuttering during speech to reduce the build-­‐up of physical tension that might otherwise lead to more sense moments of stuttering. 59 60 2/4/14 Reducing Shame & Avoidance Reducing Shame & Avoidance • Where does all that tension come from? In other words, why do people do the things they do when they stutter? • People who stutter feel an involuntary loss of control at various times when they are speaking. • Part of the answer comes from understanding the “loss of control” feeling that the speaker experiences when stuttering. • As they try to regain control, they exhibit speech and non-­‐speech behaviors. • Physical tension and struggle are actually normal reactions to the loss of control. • Compare to skating & driving 61 62 Reducing Shame & Avoidance Reducing Shame & Avoidance • The increased tension does not always solve the problem – in fact, it rarely does – but it gives the skater, the driver, the speaker the sense the he is doing something to regain control. • The foundation for learning to tolerate the feeling of loss of control is desensitization. • Another source of stuttering is embarrassment. Stuttering is embarrassing! • Stuttering sounds different, looks different, draws attention to itself, makes a person stand out. • What if the person could learn to tolerate the feeling of loss of control? • This embarrassment can lead to shame – the feeling of being “defective” or “broken.” • Skaters, Drivers, Speakers 63 64 Reducing Shame & Avoidance Reducing Shame & Avoidance • Desensitization through Pseudostuttering • In addition to tensing their muscles, people who stutter may try to HIDE their stuttering. • By pseudostuttering openly, speakers can explore their feelings about stuttering and gradually learn to tolerate stuttering. • Choosing words carefully or using “circumlocutions” to pick only words they think they can say fluently • As shame diminishes, they can proceed to more “real world” situations and continue to reduce fear. • Avoiding sounds, syllables, situations, or people • This helps them practice tension reduction strategies and, again, supports stuttering more easily. • Pretending to be sick, distracted, confused 65 66 2/4/14 Reducing Shame & Avoidance Reducing Shame & Avoidance • In addition to tensing their muscles, people who stutter may try to HIDE their stuttering. • Accepting stuttering is not easy… • You cannot simply tell a person that “it’s okay to stutter” and expect him to believe it. • Taking jobs that do not require talking, driving to a store rather than calling to see if a product is in, not asking for directions, etc. • Adolescents and adults have a lifetime of belief systems and coping patterns built around stuttering. • Avoidance is a normal, understandable reaction, but it makes it very difficult for people who stutter to communicate effectively. • They must go through a process of learning to tolerate their stuttering – and learning to tolerate other people’s reactions to stuttering. 67 68 Reducing Shame & Avoidance Reducing Shame & Avoidance • This process is called desensitization. • You cannot simply “drop” people into a stressful situation and expect them to sink or swim! • Desensitization is the process of gradually exposing clients to the thing they are afraid of. • We can help by gently guiding speakers toward experiences that reduce rather than increase fear. • People with a fear of spiders need to be gradually exposed to spiders to build up a resistance to fear. • People with a fear of heights need to be gradually exposed to tall buildings. 69 70 Reducing Shame & Avoidance Generalization • Remember that desensitization involves a gradual exposure to the things that the speaker is afraid of. • “Skills” in this context refers not only to speech fluency techniques, but also methods for accepting stuttering and strategies for reducing negative reactions. • Gradual desensitization with spiders and tall buildings. • Everything that is learned in the therapy setting has to be transferred to real world settings. • Same for stuttering. The only way to overcome fear of stuttering is by stuttering. • Avoidance works against the speaker. It does not help! “Stuttering is not a disability unless you choose not to talk.” 71 72 2/4/14 Generalization Generalization • We facilitate generalization by organizing therapy around hierarchies that can help the speaker move from easier situations to harder situations – including (particularly) situations outside the therapy room. • We do not expect the speaker to actually use the techniques in all of those situations all of the time. Our goal is to make sure that he is able to use the techniques in all situations he faces on a typical day when he wants to. • As the speaker moves along his hierarchies, he finds that he can use skills in more and more situations. 73 Generalization Generalization • Reflect on the fact that speakers do not actually face that many different situations in a typical day. • It is not unreasonable to think that a person could enter 30 to 40 situations to practice using a technique, such as easy starts or easy stuttering, during the course of therapy. The speaker is already in those situations anyway! • It seems like a lot, but count them up! We tend to do the same things day after day, so each new situation we focus on brings us closer to the goal of easier communication in all situations. 75 76 Generalization Generalization • Be sure to put the speaking situations in order. Just having a chronological or categorized list of situations is not enough, however. We also have to organize those lists in terms of difficulty, so we can put them on a hierarchy from easier to more difficult situations. Only the speaker can tell you which situations are easier for him and which are harder. • Help the student start with the easiest situations first. Then, as he achieves success with those situations, he can gradually begin to climb the ladder and move toward harder situations. 74 Success leads to success! 77 78 2/4/14 Determining Progress Determining if Progress is Being Made • Progress can be described in many different ways. • Frequency of stuttering • Reduction of physical tension • Shorter duration of stuttering events 79 80 Generalization • Progress Paradox • May show an increase in stuttering frequency. • Child will simultaneously be affected less by stuttering. • Stuttering frequency will ultimately decrease. 81 82 Fluency Assessment and Treatment Lonnie G. Harris, Ph.D., CCC-­‐SLP Clinical Competencies for Fluency Assessment & Treatment CLINICAL COMPETENCIES FOR FLUENCY ASSESSMENT 1. Must be able to differentiate between a child’s normally disfluent speech, language-­‐based disfluency, the speech of a child at risk for stuttering, and the speech of a child who has already begun to stutter. 2. Must be able to distinguish cluttered from stuttered from stuttered speech and understand the potential relationship between the two disorders. 3. Must be able to relate the findings of language, articulation, voice, and hearing tests to the development of stuttering. 4. Must be able to obtain a thorough case history from an adult client or family member of a child client. 5. Must be able to obtain a useful speech sample and evaluate it for stuttering severity. 6. Must be familiar with the available diagnostic tests for stuttering that serve to objectify aspects of the communication pattern (SSI-­‐4, TOCS, ACES, OASES, CALMS). 7. Must be able to identify environmental variables that may be related to the onset, development, and maintenance of stuttering and to fluctuations in the severity of stuttering (e.g., time pressure, emotional reactions, interruptions, nonverbal behavior, demand speech). 8. Must be able to identify disfluencies by type (prolongations, repetitions, etc.) and describe qualitatively the fluency of a person’s speech. 9. Must be able to construct a treatment program, based on the results of comprehensive testing and past treatment history. 10. Must be able to administer predetermined programs in a diagnostic way so that decisions with regard to branching and repeating of parts of the program reflect the unique needs of each client’s disorder. 11. Must be able to explain clearly to clients or their families/ significant others what treatment options are available (e.g., speech treatment, DAF, self-­‐help groups, in-­‐the-­‐ear devices) CLINICAL COMPETENCIES FOR FLUENCY TREATMENT 1. Must be familiar with the appropriate goals of treatment and the processes for achieving them and engage these processes, choosing techniques that are best for the client, and administer them with an attitude that balances the goal for normal speech with a tolerance for abnormal speech. 2. Must be flexible in choosing and changing the level of difficulty of tasks. 3. Must be able to teach clients to produce vocal tract behaviors that result in normal sounding speech. 4. Must have sufficient counseling skills to interact with clients of all ages and develop a reasonable set of expectations for the client. 5. Must have a thorough understanding of, and know how to put into practice, the principles of conditioning and learning. 6. Must understand the relations between stuttering and other related disorders of fluency (cluttering, neurogenic and psychogenic stuttering, as well as disorders of language, articulation, etc.) and identify sequences and combinations of treatment options that are helpful to the client. 7. Must understand the dimensions of normal fluency and the relation of normal fluency to speech situations and is able to work toward normal speech, with an awareness of the compromises among effort, fluency, and natural-­‐sounding communication. 8. Must understand that some stuttering behaviors may be reactions to other stuttering behaviors and knows how to plan treatment to account for this. 9. Must be able to evaluate available treatment programs with regard to treatment application for a wide variety of clients. 10. Must be able to decide, based on progress, motivational level, and cost in time and money, when it is appropriate to terminate treatment. 11. Must be aware of the continuous nature of fluency and be able to identify subtle changes in speech or other behaviors related to treatment change and explain their importance to the client. 12. Must be able to explain stuttering and treatment for stuttering to lay persons, such as daycare workers, teachers, babysitters, grandparents, and others who may influence the child’s life. 13. Must know how to develop a plan for assessing objectively the efficacy of treatment in an ongoing manner. Fluency Assessment and Treatment Lonnie G. Harris, Ph.D., CCC-­‐SLP Continuous Phonation Sequence in Fluency Therapy All the steps below are imitation. Normal prosody must be maintained at all times. If words or sentences are fluent, but there was a break in phonation, it is not considered correct. Criterion for progressing from one step to the next is a minimum of 20 consecutive correct responses. [Note that phrases do not need to be grammatically complete until you begin the Sentence level]. 1 monosyllabic word bear; walk, cup, sleep 1 bisyllabic word mother, eating, Mary, broccoli 2 words I want, dog is, horse runs, green plant 3 words I want a, dog is big, horse runs fast, green plant is 4 words I ride my bike, My sister has two, My dad fixed dinner 5 words Mom was walking with me, four dogs were eating fast 1 sentence The cow is big. I play soccer after school. Turn down the TV. 2 sentences I did my homework already. I’m going outside. What’s for dinner? I want pizza. Dad’s shirt is blue. He got it for Christmas. For older children: 3 sentences Our TV is broken. I guess I’ll go outside. Let’s play ball. The table is big. I’ll do my homework there. Will you help me? I hate making my bed. Mom makes me do it. My room is clean now. Next, proceed with picture description, which is not in imitation. Child should look at a picture and say a sentence (or two or three) about it. Now the child is adding the linguistic element to what he has previously done because he now is formulating sentences himself. He should be encouraged to used declarative sentences and ask questions. Pausing to breathe after two sentences is appropriate. 1 sentence 2 sentences 3 sentences 4 sentences Student:(______________________________________(DOB:(________________(C.A.:(__________( ( SLP:(_________________________________________(Grade/Program:(______(Date:(___________( ( ( FLUENCY(ASSESSMENT(SUMMARY( ( 1. BEHAVIORAL(COMPONENTS( ( a.(( Frequency(of(dysfluencies:(_______/per(100(syllables(produced(in(conversational(context( ( b.( (Type(s)(of(dysfluencies(observed:( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( c.( (Schwa(replacement(for(intended(vowel(observed:(((!(No(((!((Yes( ( d.( Physical(concomitants((secondary(characteristics/struggle(behaviors)(observed:( ( ( !( None(perceived( ! Only(noticeable(to(the(trained(observer( ( ( Description(of(behavior(s):(__________________________________________________________( ( ( _________________________________________________________________________________( !((Whole(multisyllabic(word(repetitions( !((Whole(monosyllabic(word(repetitions( !( PartTword(syllable(repetitions( ! PartTword(speech(sound(repetitions( ( ! Silent(or(audible(prolongations( ! Phonatory(arrests(or(sustained(articulatory(postures((blocks)( ( If(present,(average(duration(of(_____(seconds.( !( Noticeable(to(the(casual(observer( !( Distracting(or(obvious(to(the(listener( ( 2.( AFFECTIVE(COMPONENTS( a. Student(awareness(and(emotional(reaction(to(dysfluencies:( ( ( ( ( ( b. Student’s(emotional(reaction(to(dysfluencies:( ( !((Not(concerned( !((Negative(emotions(frequently(observed/reported( ( ( ( !((Not(aware( !((Often(aware( !((Mildly(frustrated( !((Occasionally(aware( !((Always(aware( !((Negative(emotions(often(observed/reported( 3.( COGNITIVE(COMPONENTS( ( a.(( Verbal(or(situational(avoidance(behaviors:( ( ( ( ( ( b.(( Peer(reactions(to(dysfluencies:( ( ( ( ( !((None(observed(or(reported( !((Occasionally(observed/reported( !((Appear(unaware( !((Some(teasing(noted/reported( !((Frequently(observed/reported( !((Consistently(observed/reported( !((Frequent(teasing(noted/reported( !( Considerable(teasing(requires(strong(adult( intervention( Fluency Assessment and Treatment Lonnie G. Harris, Ph.D., CCC-­‐SLP Fluency Assessments Assessments of Speech Behaviors Assessment of Stuttering Behaviors Tanner Academic Communication Associates (www.acadcom.com) This assessment tool can be used to collect information about a child's speech fluency at school and at home. The instrument is made up of the Parental Diagnostic Questionnaire and the Classroom Fluency Checklist. The Parental Diagnostic Questionnaire is completed by the child's parents and includes 20 questions relating to behaviors commonly observed in children who stutter. Means and standard deviations were obtained for each item. The Classroom Fluency Checklist is a reproducible form that can be completed by the classroom teacher. Stuttering Prediction Instrument for Young Children (SPI) Riley Pro-­‐Ed (www.proedinc.com) Designed for children ages 3 to 8. Assesses a child's history, reactions, part-­‐word repetitions, prolongations, and frequency of stuttered words to assist in measuring severity and predicting chronicity. Stuttering Severity Instrument (SSI-­‐4) Riley Pro-­‐Ed (www.proedinc.com) A norm-­‐referenced assessment that measures stuttering severity in both children and adults in the four areas of speech behavior: (1) frequency, (2) duration, (3) physical concomitants, (4) naturalness of the individual’s speech. Percentiles are in reverse order to other norm-­‐referenced tests. Test of Childhood Stuttering (TOCS) Gillam, Logan, & Pearson Pro-­‐Ed (www.proedinc.com) Provides clinicians and researchers with a sound method for assessing speech fluency skills and stuttering-­‐related behaviors in children 4-­‐12. Its main purposes are to (1) identify children who stutter, (2) determine the severity of a child’s stuttering, and (3) document changes in a child’s fluency functioning over time. It can also be used as a tool in research on childhood stuttering. Attitude Scales Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES) Yaruss & Quesal Pearson (www.pearsonassessments.com) The OASES is designed for ages 7-­‐18 and it uniquely measures the impact of stuttering on a person’s life—unlike most other stuttering instruments. This brief, yet comprehensive self-­‐report, is built on a solid theoretical foundation to help you assess the impact of stuttering in multiple life situations. It is to be used as an evidence-­‐based tool to support effective intervention. Cognitive, Affective, Linguistic, Motor, and Social Assessment Model (CALMS) Healey, Trautman, & Susca Available free online at http://cehs.unl.edu/fluency/pdfs/calmsrate.pdf. This rating scale is designed to evaluate cognitive, affective, linguistic, motor, and social components that are related to stuttering. It is recommended that clinicians base their clinical judgment on deriving a score for each item using scores and/or data from scales, tests, as well as documented evidence about the child being evaluated. Take the scores for each rated item and divide by the total number of items scored within each component to obtain an average score for each component. The average component scores become the data points for plotting the CALMS profile. Assessment of the Child’s Experience of Stuttering (ACES) Yaruss, Coleman, & Quesal Available free online at http://arslpedconsultant.com/documents/Handouts%20ABCs%20of%20Stuttering/ACES%20Draft%209-­‐27-­‐06.pdf The form is to be completed by the student and it includes four sets of questions that ask about his/her speech. A-­‐19 Scale for Children Who Stutter Andre & Guitar Available free online at http://arslpedconsultant.com/documents/Handouts%20ABCs%20of%20Stuttering/A-­‐19%20Scale.pdf The form is to be completed by the student and it includes four sets of questions that ask about his/her speech. Student: ______________________________________ DOB: ________________ C.A.: __________ SLP: _________________________________________ Grade/Program: ______ Date: ___________ Frequency of Disfluencies Type(s) of Disfluencies Phonatory Arrests/ Sustained Artic. Postures (blocks) Speech Sound Prolongations Schwa Replacement Physical Concomitants FLUENCY RATING SCALE Non-­‐Disabling Severe 3 4 3-­‐8% stuttered syllables in conversation (based on minimum of 300 syllable sample). 2 Mostly whole monosyllabic word repetitions. Repetitions are rapid, tense & irregularly paced. Pitch rise may be present. > 15% stuttered syllables in conversation (based on minimum of 300 syllable sample). 6 Frequent part-­‐word speech sound repetitions. Frequent prolongations and broken words. Repetitions are rapid, tense and irregularly paced. Pitch rise may be present. Long, tense blocks, some with noticeable tremors. 0 None observed or less than .5 seconds duration 4 0.5 to 2.0 seconds in Duration 8-­‐15% stuttered syllables in conversation (based on minimum of 300 syllable sample). 4 Mostly part-­‐word syllable repetitions. Occasional speech sound repetitions. Prolongations and broken words noted. Repetitions are rapid, tense & irregularly paced. Pitch rise may be present. Phonatory arrests / sustained articulatory postures are noted. 6 2.1 to 3.0 seconds in duration 0 None observed or less than 1.5 seconds duration 0 Not perceived 0 Not perceived 4 1.6 to 3.0 seconds in Duration 6 3.1 to 4.0 seconds in Duration 8 4.1 or more seconds in duration 0 Not perceived 2 Only noticeable to trained observer. 2 Student is occasionally aware and mildly frustrated by dysfluencies. 0 Not perceived 4 Noticeable to casual observer. 4 Student is often aware of dysfluencies. Negative emotions are often observed/reported. 4 Verbal or situational avoidance frequently observed or reported. Frequent teasing noted or reported. 6 Perceived 6 Distracting or obvious to the listener. 6 Student is always aware of dysfluencies. Negative emotions are frequently obs./reported. 6 Verbal or situational avoidance consistently observed or reported. Considerable teasing requiring strong adult intervention. 8 Seriously limits performance in the educational setting. 0 Student is neither aware of, nor concerned about, dysfluencies. Avoidance Behaviors and Peer Reactions 0 No verbal or situational avoidance observed or reported. Peers appear unaware of dysfluencies. Adverse Effect on Educational Performance 0 No interference with performance in the educational setting. Moderate 2 Awareness and Emotional Reactions Total Score Rating Scale Mild 0 < 3% stuttered syllables in conversation (based on minimum of 300 syllable sample). 0 Mostly whole multisyllabic word repetitions. Occasional whole-­‐word interjections and phrase/ sentence revisions. 0 – 16 0 – Non-­‐Disabling 2 Verbal or situational avoidance occasionally observed or reported. Peers are aware of dysfluencies; some teasing noted reported. 4 Minimally impacts performance in the educational setting. 17 – 27 1 – Mild 6 Moderately interferes with performance in the educational setting. 28 – 40 2 – Moderate 8 3.1 or more seconds in duration 41 – 58 3 – Severe Student: ______________________________________ DOB: ________________ C.A.: __________ Respondent: __________________________________ Grade/Program: ______ Date: ___________ TEACHER/PARENT INTERVIEW: FLUENCY Sometimes Never Always 1 2 3 4 5 1. Does the student verbalize appropriately? 2. Does the student verbalize effortlessly? 3. When verbalizing, are the student’s facial and body movements appropriate? 4. Does this student readily participate in class discussions or activities that require speaking in front of groups? 5. Do YOU accept the student’s pattern as adequate? 6. Do PEERS accept the student’s pattern as adequate? 7. Do you understand the student’s verbal intent without difficulty? 8. Does the student readily participate in conversation with peers? Please explain below. 9. Does the student’s speech allow for participation/progress in the general curriculum? Please explain below. Explanations to questions #8 and #9: __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ Do you have any other observations related to the communication skills of the student? ________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________ Respondent’s Signature ________________________ Relationship to Student _________ Date Name: _________________________________________ Age: ___________ Date: ___________________ Protocol for Differentiating the Incipient Stutterer from the Normally Disfluent Child Auditory Behaviors TYPE OF DISFLUENCY 1 Probably Normal 2 Interjections Questionable Hesitations Whole-word reps Coexisting struggle 3 Probably Abnormal Part-word reps Prolongations SIZE OF SPEECH UNIT AFFECTED 1 Probably Normal 2 Sentence/phrase Questionable Word 3 Probably Abnormal Syllable/sound FREQUENCY OF DISFLUENCIES § Frequency of Repetitions 1 Probably Normal 2 < 2% § 2% to 5% Probably Normal 3 < 1% § Probably Abnormal 3 Probably Abnormal >5% Probably Abnormal 1% or greater Frequency of Overall Disfluencies 1 3 Frequency of Prolongations 1 Questionable Probably Normal 2 < 5% Questionable 5% to 10% >10% DURATION OF DISFLUENCIES § Typical Number of Reiterations per Part-­‐Word Repetition = __________ 1 Probably Normal 2 <2 Questionable 2 to 5 § Average Duration of Prolongations = __________ 1 Probably Normal 3 < 1 second Probably Abnormal 1 or more seconds 3 Probably Abnormal >5 AUDIBLE EFFORT (mark all that apply) 1 Probably Normal 3 Lack of the following: Probably Abnormal Presence of the following: o Hard glottal attacks o Disrupted airflow o Vocal tension o Pitch rise o Others: ____________________________________________________________________ RHYTHM / TEMPO / SPEED OF DISFLUENCIES 1 Probably Normal 3 Slow / Normal Evenly paced Probably Abnormal Fast Irregular SCHWA REPLACEMENT 1 Probably Normal 3 Replacement not observed Probably Abnormal Replacement observed AUDIBLE LEARNED BEHAVIORS (mark all that apply) 1 Probably Normal 3 Lack of the following: Probably Abnormal Presence of the following: o Circumlocutions o Avoidance tactics (postponers) o Starters Visual Evidence FACIAL GRIMACES & ARTICULATION POSTURING 1 Probably Normal 3 Not Observed Probably Abnormal Observed HEAD MOVEMENTS 1 Probably Normal 3 Not Observed Probably Abnormal Observed BODY INVOLVEMENT 1 Probably Normal 3 Not Observed Probably Abnormal Observed Protocol Score & Interpretation Total Score: ______________ 14 42 | 15 20 25 3 0 3 5 4 0 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Probably Normal Probably Abnormal (21 or more points) Fluency Assessment and Treatment Lonnie G. Harris, Ph.D., CCC-­‐SLP Structured Activities in Fluency Therapy Games stimulate interest in therapy -­‐ Games have a standard form and series of responses, providing greater ease of comparison within the clinical course for a child (as well as across children) to help define areas of strength and weakness. Create a realistic distraction that can provide practice in attending to the production of speech changes in the real world outside the clinic. Games serve as home therapy transfer activities – Playing games is an important part of childhood and games used in therapy can serve as home therapy transfer activities. Many children who stutter may be limiting their participation in games (and thus limiting their interaction with other children) because of the speech challenges that the games present. When these children understand that they can be more fluent while playing game, they will have an easier time overcoming fears and anxieties. Types of Games There are a number of games that you can use in fluency therapy: Memory-­‐Matching Games – Memory-­‐matching games can address language complexity at the word level and carrier phrase level. Memory-­‐matching games typically involve matching pairs of cards or chips that are shuffled and placed face down on the table. The most common game is Concentration. Players draw one card and then try to find its match. Speech activities can involve announcing the content of the cards in one or more words (“flower; bee”) or using a carrier phrase (“I found a flower; I found a bee.”). Fluency activities could include stretches or slow and easy bounces on the words (“flo-­‐flo-­‐flower; bbbbbbee”) or on specified components of the carrier phrase “IIIIII found a fffffflower”). You can use variations of commercially-­‐available games, such as Go Fish, I Spy, Battleship. Blocks – Games using blocks can address language complexity at the word level, the carrier phrase level, and the conversational level. Building blocks can be used together with drill activities as rewards. For example, a child can be awarded a building block for each successful production of a target activity (easy onset, stretches, slow bounces, pullouts, etc.). They can be used in request activities, using carrier phrases (such as IIIII want a yyyyyyellow block”) or they can be used in free-­‐from play, with you and the child interacting and conversing as you both build a house or other structure. You can allow a talkative child to converse or you can elicit speech by asking leading questions (“How do you think we make this part of the garage higher?”). Role-­‐Playing Games – Many very young children (ages 2-­‐4) respond best to play with toys rather than games involving verbal stimuli. If you are working with the preschool population, you will find this group to be a challenge. Your challenge is to turn nonverbal play into a stimulating speech-­‐language activity without intruding on the child’s creativity. If the child is used to playing in silence, the first step is you to begin actively vocalizing in the ways that reinforce or mirror his play, without being intrusive. Such verbalizations should reflect the level of cooperative play the child is accustomed to engaging in. If he desires or is used to parallel play, you can matter-­‐0f-­‐factly make statements about what you are doing and what the child is doing. After a while, this may stimulate the child to begin mirroring his own activities with verbalizations. The goal is to encourage cooperative play, which is age-­‐ appropriate for most children who are beginning to stutter. Of course the ultimate goal is to encourage open speaking, open stuttering, and open modification of stuttering behaviors. Here is an example of how a role-­‐playing game can be used… Your client is Billy, who loves playing a game involving a plastic flying dinosaur (the child’s stuttering) and a Batman action figure (Billy as the self-­‐therapist). During the game, Billy (in the role of Batman) first uses “hard” speech (fluent speech with hard onsets of phonation) and imitations of “pushing” behavior, which would cause the dinosaur (controlled by you) to take off and start destroying a block city. If Batman continues to address the dinosaur using hard speech, the destructive activities would simply increase. However, if Batman used a gentle speaking style using “easy” speech (stretches and slow bounces), the dinosaur would calm down and eventually go to sleep. With the dinosaur close at hand, you can monitor Billy’s productions during the remainder of the therapy session. If is speech begins to get hard and rushed, the dinosaur might come back to life, requiring a return of Batman and his easy speech to save the day. Card Games – Card Games used in therapy can address language at the word level and carrier phrase level. Some SLPs say that all they need to conduct a stuttering therapy session is a deck of UNO cards. Though this might be an exaggeration, much can be done with a simple card game. The main difference in playing a card game for stuttering therapy is that all moves and activities are announced openly in speech, using a fluency or modification techniques. For example, in UNO, rather than just playing a card, each player uses a carrier phrase to announce: “IIIIII have a green sssssssssiiiix.” Iiiiiii have to dra-­‐dra-­‐dra-­‐draw.” “I pppppass”, and so on. The pace of the game is such that dozens of repetitions o f these techniques and others can be accumulated in a very short time. The limitation of card games like UNO is that, with their limited word set and language complexity, they may quickly become too easy for children to benefit; however, they can still be used as warm-­‐ ups or to practice newly introduced techniques.” Board Games – Board games can be used in therapy to address language at the word level and carrier phrase level, reading, and complex utterance. Board games come in a large range of type and complexity, from word-­‐level games to games involving carrier phrases, complex reading skills, and conversation. They offer the advantage of engaging both clinician and child in a cooperative activity where speech can be unstructured and modifications can be modeled by the clinician and performed by the child. Which Game to Use? A hierarchical approach should be used when selecting games for use in therapy. Early in the intervention process, it is important to use very simple games with which the child can achieve success in increasing fluency without continual reminders from you. The definition of “simple” will vary from child to child, but most memory games, UNO, and games that can be played with rote responses involving numbers, letters, or colors ( such as Battleship) will qualify. If excessive cueing is required, this may be an indication that the game is too complex for the child to manage while simultaneously working on fluency-­‐shaping or stuttering modification techniques. The focus should always be on speech activities rather than the games that are coincidently used to provide the speech stimulus. In Battleship, for example, each player may simply announce the location of the square he wants to hit, using an easy prolongation, stretch, or pseudo-­‐stutter. Alternatively, a simple phrase as, “I hit E six” or “I shoot C nine” can be used with easy prolongation on “I” and the number. Similar use can be make of memory games, in which the child turns over two tiles at a time, seeking a match. He can either identify the object on the tile (“antelope”) or be encouraged to use a short carrier phrase (“IIIIII found an aaaaaaantelope). Once the child has mastered easy games and his therapy moves on to longer carrier phrases and sentences, more complex types of games (discussed earlier) can be used. Expressive language and reading speech modalities can be explored by selecting question-­‐response games: • • • Mystery Garden or Guess Who, in which players try to identify a tile or card helped by the opponent. Twenty Questions or Pay Day, which use cards that must be read aloud. A good intermediate game is Outburst Junior, which uses both of these modalities and uses short questions and one-­‐ or two-­‐word answers. Fluency Assessment and Treatment Lonnie G. Harris, Ph.D., CCC-­‐SLP Tips for Teachers -­‐ FAQ What should I do when a child stutters in my class? The most important thing to do when a child is stuttering is to be a good communicator yourself. • Keep eye contact and give the child enough time to finish speaking. • Try not to fill in words or sentences. • Let the child know by your manner and actions that you are listening to what she says—not how she says it. • Model wait time — taking two seconds before you answer a child’s question — and insert more pauses into your own speech to help reduce speech pressure. These suggestions will benefit all of the children in your class. Do not make remarks like “slow down,” “take a deep breath,” “relax,” or “think about what youʼre going to say, then say it.” We often say these things to children because slowing down, relaxing, or thinking about what we are going to say helps us when we feel like weʼre having a problem tripping over our words. Stuttering, though, is a different kind of speaking problem; and this kind of advice is simply not helpful to the child who stutters. Should I remind the child to use his stuttering therapy techniques in class? Unless the child or an SLP specifically asks you to help remind the child, it may be best not to. In therapy, children who stutter learn several different techniques, sometimes called speech tools, to manage their stuttering. However, learning to use these speech tools in different situations (e.g., the classroom vs. the therapy room) takes considerable time and practice. Many young children who stutter do not have the maturity to monitor their speech in all situations. Therefore, it may be unrealistic to expect the child to use her tools in your classroom. What should I do when the child is having a difficult speaking day? It’s always best to check with the child about what he would like you to do on days when talking is more difficult. Children who stutter vary greatly in how they want their teachers and peers to respond when they are having an especially difficult time talking. One child may prefer that his teacher treat him in the same way as the teacher would any other day, by spontaneously calling on him or asking him to read aloud. On the other hand, another child may want his teacher to temporarily reduce her expectations for his verbal participation, by calling on him only if his hand is raised or allowing him to take a pass during activities such as round-­‐robin reading. What should I do when the child who stutters interrupts another child? Handle interruptions the same way that you would for a child who doesn’t stutter. Children who stutter sometimes interrupt others because itʼs easier to get speech going while others are talking. Were not sure exactly why itʼs easier to talk over others, but it may be because less attention is called to the child at the beginning of her turn when stuttering is most likely to occur. Even though it may be easier to get her speech going by interrupting a peer, it’s important for the child who stutters to learn the rules for good communication just like all the other children in your class. How can I make oral reports easier for the stuttering child? There are many things you can do to help make oral reports a positive experience for the child who stutters. Together, you and the child can develop a plan, considering factors such as: • Order—whether he wants to be one of the first to present, in the middle, or one of the last to present • Practice opportunities—ways he can practice that will help him feel more comfortable, such as at home, with you, with a friend, or at a speech therapy session • Audience size—whether to give the oral report in private, in a small group, or in front of the entire class • Other issues—whether he should be timed, or whether grading criteria should be modified because of the stuttering Should I talk to the entire class about stuttering? You will need to discuss this idea with the child and in consultation with the child’s SLP. Some children wonʼt mind if you talk to their peers about stuttering. Others, however, will feel that stuttering is a private matter and should not be discussed openly with the other children in class. Sometimes, a child who stutters will make a classroom presentation about stuttering. This presentation allows the child to teach her peers facts about stuttering, give them names of famous people who stutter, offer suggestions about how she would like her peers to react when she is stuttering, and even teach the others different ways to stutter. One of the benefits we’ve observed from having a child who stutters make a classroom presentation about stuttering is a reduction in teasing. If other children understand more about the problem, they are less likely to ridicule or tease the child who stutters. This is not an appropriate activity for all children who stutter, as some may not be ready yet to deal with stuttering in such an open way. Giving a presentation about stuttering is one component of stuttering therapy, typically done in conjunction with a classroom visit by the SLP. If you have questions about whether the child in your class is ready to give such a presentation, consult the SLP. If a child in your class is going to make a presentation about stuttering, the Stuttering Foundation has a Classroom Presentation Packet (#0130) with brochures, information, and posters you and the child can use. How should I handle teasing? Deal with teasing of the child who stutters just as you would with any other child who is being teased. Unfortunately, teasing is an experience common to many children. As mentioned earlier, classroom presentations can be a powerful way to reduce teasing if the child who stutters is ready to make such a presentation. At other times, teasing will be stopped only with your intervention. Many school districts now have written policies for handling teasing in the classroom, and school counselors or social workers are excellent sources of information. A book with humorous and practical suggestions for teasing is Bullies Are a Pain in the Brain, by T. Romain of Free Spirit Publishing. Here are some other suggestions: • Listen to the child and provide support right away. Don’t dismiss teasing with a remark such as “Everybody does it.” • Discuss problem solving and coping strategies for teasing and bullying with the child and choose several that suit him or her. These problem solving and coping strategies may also be a part of speech therapy. • Educate others. The more others know about stuttering, the less likely they will be to tease. • Talk with the class about teasing and bullying in general. The child who stutters is probably not the only one being bullied or teased. • Talk with parents, the speech pathologist, and other teachers so that you are all on the same page. What types of things can I say to encourage the child who stutters to talk in my class? The best way to encourage a child who stutters to talk in your class is to let him know through your words and actions that what he says is important, not the way he says it. Other ways you can encourage the child: • Praise him for sharing his ideas • Tell him that stuttering does not bother you • Give him opportunities to talk, such as calling on him to give an answer or asking him for his opinion • Let him know it’s OK to stutter