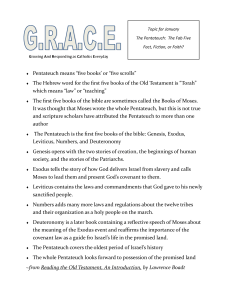

The Meaning of the Pentateuch

advertisement