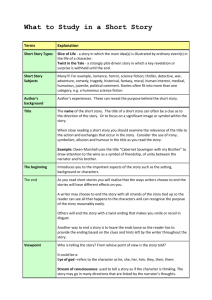

Style Manual

advertisement