Psychic Distance and FDI Location Choice: Empirical Examination

advertisement

Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

www.apmr.management.ncku.edu.tw

Psychic Distance and FDI Location Choice:

Empirical Examination of Taiwanese Firms in China

Chin-Lung Kuo*, Wen-Chang Fang

Department of Business Administration, National Taipei University, Taiwan

Accepted 18 June 2008

Abstract

Around the world, China fever has replaced China fear. Multi-national enterprises (MNEs)

are doing more than just talking about foreign direct investment (FDI) in China. Differences

in local thing in their broadest senses, including policy barriers at the borders, nature and

geography, and economic differences, contribute to its distinctiveness. Thus, this study

reviews, discusses and re-conceptualizes the psychic distance concept through the CAGE

distance framework and empirically assesses its validity for three economic regions within

China each of which have unique characteristics. The investigation concluded that psychic,

administrative, and geographic distances were negatively related to location choice, owing to

smaller perceived uncertainty. Thus, numerous Taiwanese have invested in China after

considering the complex political situation across the straits. Even if the theoretical psychic

distance (using cultural distance as a proxy variable) cannot consistently explain the

phenomenon of the location choice in a large country, this investigation identifies the CAGE

framework as potentially useful. Moreover, this study uses a cross-sectional survey of 258

Taiwanese firms investing in China across industries and received result to support the

hypothesis. Additionally, the influence of psychic distance on location choice reduces with

increasing experience of top management.

Keywords: Psychic distance, location choice, CAGE framework

1. Introduction

Recently, numerous MNEs have been talking about China Fever. Moreover, the influence

of China is only going to strengthen as their economy and purchasing power grows. It is

uncertain just how much direct-investment money has flooded into China. However, for

MNEs from Europe or America, China represents a totally different market which may

require special approaches to business operations. Thus some European and American MNEs

have invested in China directly, while others have done so indirectly, for example by

cooperating with Hong Kong partners. Let’s give this phenomena an explanation: China

Fever attracts MNEs, but then China Fear keep then away.

In almost all theories, scholars assume that people are rational, but “fear” is irrational.

Logically, rational decision makers should analyze opportunities and treats, in addition to

internal resources and capabilities, to determine whether to invest, and particularly for

selecting location and entry mode. There is no need for fear. In fact, according to our

_____________________________

*

Corresponding author. E-mail: marble.kuo@gmail.com

85

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

observation, selection decisions in foreign markets are beyond rationality, and are influenced

by psychological factors which influence top management decision behavior, including home

country bias and representative bias.

Foreign firm selection of its location in a host country is critical to its success. Therefore,

location choice is a key decision in determining international expansion. Additionally,

scholars of economic geography provide alternative perspectives. Such scholars assert that

firm clustering (proximity) at a unique location will generate positive externalities that attract

the firm to a specific location (Nachum, 2000). Furthermore, Porter (1998) proposed the

diamond model as a means of determining this local advantage. As Porter put it, ‘local thing’

is an important factor to compete globally, and industrial clusters provide the best evidence of

that concept. If host country location does indeed still matters, then so too does the distance

between the home and the host. Restated, local thing matters local advantages.

Regardless of the location chosen, the uncertainty of foreign market (O’Grady and Lane,

1996), the factors that prevent or disturb the flow of information(Vahlne and Wiedersheim-Paul,

1973), and factors preventing or disturbing firm’s learning about and understanding of a

foreign environment(Nordstrom and Vahlne, 1994) cause the risky sense. In these circumstances,

China is difficult to understand, difficult to learn about and is characterized by restricted

information flows. So, what cause these western firms feel risky in entrancing China? We can

say, extremely different culture, such as Confucianism, Tao and Buddhism, from the western

MNEs’ think ways and this makes the feel of unknown or uncertainty. Meanwhile, language

distortion and local information “decoding” requires experienced mangers. If so, will

experienced executives fear less? Moreover, the nature of their interaction is also interesting.

This study focuses on these two issues.

Traditionally, international business scholars have stressed the unique factor endowments

of individual locations, and the concept of distance in international business can be traced all

the way back to Adam Smith. Beckerman (1956) later empirically assessed location

sensitivity for international business transactions. Dunning proposed his OIL paradigm which

stresses location advantage. In short, monitoring trade and investment among different

locations can determine the sensitivity of distance in the internationalization process.

Psychic distance is the specific term used by international business researchers to express

the perceived distance of a specific location and represent the ease or difficulty of conducting

global business operations, such as, Child et al.(2002), Clark and Pugh (2000), Evans and

Mavondo (2002), Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975), Nordström and Vahlne (1994),

Sousa and Bradley (2005) argued that psychic distance significantly impacts the firm

international marketing strategy, particularly the degree of marketing program adaptation.

Meanwhile, numerous researchers have challenged the psychic distance. The most

controversial in external distance presently is the dimensional approach. Hofesteds’ psychic

distance referred to “cultural distance”. Moreover, Evans and Mavodo (2002) defined psychic

distance as the composition of cultural and business distance. Welch and Luostarinen (1988)

applied a three dimensional approach to conceptualize and examine business distance.

Ghemawat (2001) encompassed geographic, cultural, economic and administrative

dimensions in redefining psychic distance. The most noteworthy of these dimensions was the

dimension of administration, there are not obviously highlight before. I believe the distance

between the people of Taiwan and China is the result of different administrative systems. The

framework, proposed by Ghemawat(2001), maybe possesses specific and additional

explanatory power for foreign direct investment (FDI) studies of Taiwanese firms in China.

This study addresses the role played by psychic distance in location choice by top

management. This study reviews, discusses, and re-conceptualizes the concept of psychic

distance utilizing the CAGE distance framework, and then empirically assesses its validity in

three economic regions of China that presents with different characteristics. This study

86

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

contends that distance remains an important concept; thus, this study aims to obtain a clearer

understanding of the potential importance of distance for design and management of firms.

More specifically, this study focuses on how different distances— cultural, administrative,

geographic, and economic — can affect the process of the determination of psychic distance

by top-management. This model was proposed by Ghemawat (2001).

The discussion concludes that the psychic distance and administrative and geographic

distance were negatively related to location choice owing to smaller perceived uncertainty

across the strait. Thus, many Taiwanese firms invested in China following considering the

complex political situation across the straits. This study also proposes that even if the

theoretical psychic distance (using cultural distance as a proxy variable) cannot explain the

phenomenon of location choice in a large country, the CAGE framework may be useful for

compiling an explanation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the

research model, presents theoretical justifications, and develops hypotheses. What follows are

the details of operationalization of the construct, the survey instrument, and the data collection.

This section is followed by data analysis, discussion of the results, as well as a summary of

the limitations of this study, and concluding remarks.

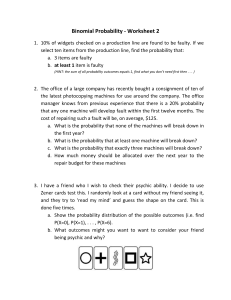

Psychic Distance

Cultural Dist.

Admin. Dist.

Geographic Dist.

Economic Dist.

Location

Choice

Top management

Background

Figure 1. Conceptual framework

2. Research model

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of psychic distance and location choice. The Table 1

summarizes the definitions of various model constructs

Table 1. Definitions and constructs in the model

Construct

Psychic

distance

Definition

The extent to which top-management perceives the degree to which

a set of factors prevents or disturbs information flow between firms

and foreign markets.

Cultural

distance

Administrative

distance

Differences in religious beliefs, races, social norms, and languages.

Geographic

distance

Economic

distance

Location

choice

Differences in a set of factors, including absence of colonial ties,

absence of shared monetary or political association, political

hostility, government policies, and institutional weakness.

Differences in a set of factors, including physical distance, lack of

common borders, lack of sea or river access, weakness of

transportation, and communication links and climate.

Differences in consumer incomes and the cost and quality of

infrastructures and natural, financial, and human resources.

Firm decision to either invest or not invest in a particular location

for specialized activities.

87

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

2.1 Location choice—the FDI attraction

Managers of MNEs are increasingly able to segment their activities and seek the optimal

location for specialized activities. This ability to separate and relocate stages of production

has driven a manufacturing boom in China and a service industry boom (for example, call

centers) in India.

Scholars in international business have argued that location decisions are influenced

primarily by agglomeration economies and location advantages. Other factors, such as public

incentives (namely, tax, tariffs) and other forms of barriers, are represent complementary

factors. Classical FDI theorists argue that money flows away from areas with abundant capital,

which offer a low rate of return, and flows towards capital poor areas, which offer a high rate.

Firms also adjust their locations to move away from locations with high inefficiency and thus

low performance, and towards those with good efficiency and high performance. The socalled OLI paradigm proposed by Dunning summarizes Ownership advantages, Locationspecific advantages and Internalization as three drivers of firm internationalization.

Consequently, the location choice should be further classified based on three motivations for

FDI.

FDI is rational or efficiency-seeking when firms can benefit from the common governance

of geographically dispersed activities in the presence of economies of scale and scope.

Conceptually, location can affect costs in several ways. Locations differ in terms of the

prevailing costs of labor, management, scientific personnel, raw materials, energy, and other

changing factors. Location can also affect firm infrastructure cost owing to differences in

local infrastructure availability. Climate, cultural norms, and tastes also differ with location.

Finally, location frequently impacts logistical costs. Location thus should be considered a

separate cost driver (Porter, 1990).

When firms invest abroad to gain access to resources unavailable in their home country,

their investment is termed resource- or asset-seeking FDI. The resources involved may

include natural resources, raw materials, or low-cost inputs such as labor.

Market-seeking FDI is performed to sustain existing markets or exploit new markets. This

type of investment is designed to better serve a local market via local production, market size

and market growth of the host economy, which are the main factors encouraging marketseeking FDI. Impediments to serving the market, such as tariffs and transport costs, also

encourage such FDI.

Many studies have demonstrated that FDI is disproportionately concentrated in states with

agglomeration economies. The so-called industrial clusters are receiving more attention from

certain scholars, such as Nohria (1991), McEvily and Zaheer (1999), and Porter (2003).

Location seems more important, and the enduring competitive advantage in a global economy

is increasingly important in local terms. World-class mutual-fund companies in Boston,

textile-related companies in North Carolina and South Carolina, high-performance auto

companies in southern Germany, and fashion shoe companies in northern Italy, are examples

of such enduring competitive advantage (Porter, 1998).

Previous empirical studies examining firm location choice include Coughlin et al. (1991)

and Levinson (1996). Coughlin et al. (1991) examined how the characteristics of individual

states influence the location choices of foreign firms investing in manufacturing facilities in

the United States. Using data from 1981-1983, they found that states with higher per capita

incomes and more intensive manufacturing activity attracted relatively more FDI.

In short, regardless of the reasons for market-seeking, resources-seeking, efficiency

seeking, or externality of agglomeration economies, location choice should closely fit the

motives of FDI. This investigation focuses on the perceived location-specific advantages at

88

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

the intra-country level as determinants of location choice to explain the geographical

distribution of FDI inflows across intra-country in China. Large market size, proximity to

home market, low-cost labor and favorable tax treatment in the host country are all considered

to be the same at the intra-country level.

2.2 Psychic distance

The concept of distance in international business has been identified as a key explanatory

factor (Johanson and Vahlne,1977; Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975; Nordstrom and

Vahlne,1994; Vahlne and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1977) . In 1956, Beckerman first used the term

“psychic distance” to highlight the need for a broader definition of distance in international

business research. The concept of psychic distance implies that companies perform best in

foreign markets that closely resemble their domestic market. (Johanson and WiedersheimPaul, 1975; Nordstrom and Vahlne,1994). Since the 1970s most scholars have taken this

concept to represent] the psychological distance between the home country and the trading or

investing country or countries .

Technology has reduced the costs associated with distance, and developments in

transportation technology and distance-spanning information and communication technology,

including e-mail and video conferencing, have led numerous researchers and practitioners to

believe that the traditional distance sensitive internationalization process no longer makes

sense in a rapidly globalizing world. Much has been made recently of the “death of distance”

(Cairncross, 1997); restated, the current belief is that “distance does not matter”.

Although, there no doubt exists the diminishing of distance, the truth is that distance is

still distances, still there ,never changes, and just need some modification. Since

Hofstede(1983) presented the construct of culture distance and scale, many scholars have

commonly used cultural distance as a proxy for psychic distance. Using this review of the

psychic distance construct, Evans and Movando (2002) proposed defining psychic distance as

the distance between the home market and a foreign market, determined by perceptions of

both cultural and business differences, while business distance is created by legal, political,

economy, business practice and language differences. Luostarinen (1980) defined economic

and geographic distance as business distance. This study avoided using economic and

geographic distance as proxies for business distance because most of those costs and risks

result from business barriers created by distance. Distance describes not just geographic

separation, although that is also important. Distance also has cultural, administrative, political,

and economic dimensions that can make foreign markets considerably more or less attractive

(Ghemawat, 2001). Additionally, intra-country studies rely heavily on the administrative,

geographic, and economic factors of local system. Thus, the concept of psychic distance must

be renewed. Ghemawat (2001) incorporated geographic, cultural, economic and

administrative dimensions in redefining psychic distance, renaming the concept the CAGE

distance framework. However, the literature to date has not examined the effect of psychic

distance on location choice using the redefined concept of the CAGE framework.

89

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

Table 2. Definitions of psychic distance

Professor

Definitions

Vahlne and Wiedersheim-Paul The authors defined psychic distance in terms of

factors that prevent or disturb the flow of information

(1973)

between suppliers and customers.

Lee (1998) and Swift’s (1999) definitions of cultural

Lee (1998) and Swift (1999)

distance are often treated as synonymous with

psychic distance. Cultural distance is defined as

“. . .the perceptions of international marketers

regarding the socio-cultural between the home and

target countries in terms of language, business

practices, legal and political systems and marketing

infrastructure” ( p. 9).

The authors stated that “cultural differences among

Kogut and Singh, (1988)

countries influence managerial perceptions regarding

the costs and uncertainty of alternative modes of

entry” [pp. 413-414].

Kogut and Singh (1988) estimated national cultural

distance as a composite index based on the deviation

from each of Hofstede’s (1980) national culture

scales: Power distance, uncertainty- avoidance,

masculinity/femininity, and individualism.

Nordstrom and Vahlne (p.42) subsequently redefined

Nordstrom and Vahlne (1994,)

psychic distance as “factors preventing or disturbing

firm learning about and understanding of a foreign

environment”.

O’Grady and Lane (p.330) defined psychic distance

O’Grady and Lane (1996, )

as “. . .a firm’s degree of uncertainty about a foreign

market resulting from cultural differences and other

business difficulties that present barriers to learning

about the market and operating there.”

Argues that “. . .(P)sychic distance is a consequence

Swift (1999)

of a number of inter-related factors, of which,

perception is a major determinant.” (p. 182)

Proposed defining psychic distance as “the distance

Evans and Mavondo (2002)

between the home market and a foreign market,

resulting from the perception of both cultural and

business differences.” ( p.517 ). This definition helps

to clarify inconsistencies in the previous research by

specifically incorporating the elements of perception

and distance and by referring to both cultural and

business differences.

2.3 CAGE framework

Location advantages describe immobile factor endowments and inputs that are unique to

specific locations, including infrastructure, institution and other productive resources. By

exclusively emphasizing potential sales, the costs and risks of doing business in a new market

can be ignored. Most of those costs and risks result from barriers created by distance.

Distance describes not simply geographic separation, although that is also important, but also

has cultural, administrative, political, and economic dimensions that can significantly

90

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

influence the attractiveness of foreign markets (Ghemawat, 2001). Each of these distance

dimensions encompasses many different factors, some of which are readily apparent while

others are quite subtle.

Intra-country differences go beyond simply being cultural, and differences in

infrastructure and input factors are vital for this kind of studies. (Gong, 1995; Wei et al., 1999;

Head et al., 1995; Head and Ries, 1996; Shaver, 1998). Following this logic, it can be argued

that (psychic) CAGE distance affects firm choice of location in four broad ways: (a) by

understanding the cultural distance based in the area; (b) by scaling administrative aspects

between governments, which underpin political constraints; (c) by measuring the geographic

distance, which created physical limitations for the cluster; and (d) by examining the

economic difference.

Ghemawat (2001) argued that the distance between two countries can manifest itself along

four basic dimensions: Cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic. Distance types

influence different businesses differently. For example, geographic distance affects the costs

of transportation and communications, and thus is particularly important to companies dealing

in heavy or bulk products or whose operations require high coordination among highly

dispersed people or activities. The cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic (CAGE)

distance frameworks help managers identify and assess the impact of distance on various

industries. Thus distance still matters.

Psychic distance influences market selection decisions during the internationalization

process, since companies are likely to select countries generating low psychic distance as the

companies begin their internationalization process. Firms appear to start by exporting to

neighboring/culturally close markets, before entering more physically distant ones (Bilkey

and Tesar, 1977). Therefore, based on the arguments supporting attractiveness of a location

with a psychic distance concept, it is hypothesized that:

H1: A positive association exists between reducing psychic distance and location

attractiveness.

2.3.1 Cultural distance

National cultural attributes determine how individuals interact with one another and with

companies and institutions. Differences in religious beliefs, race, social norms, and languages

can all create distance between two countries. Since Hofstede (1983) argued the construct of

culture distance and its scale, many scholars have used culture distance as a proxy of psychic

distance. Using this review of the psychic distance construct, Evans and Movando (2002)

proposed that psychic distance should be defined as the distance between the home market

and a foreign market, determined by the perception of both cultural and business differences.

Certain cultural attributes, such as language, are easily perceived and understood, while

others are much more subtle. Social norms, the deeply rooted system of unspoken principles

that guide individuals in their everyday choices and interactions, are often nearly invisible,

even to those who abide by them.

Most frequently, cultural attributes create distance by influencing consumer choices

between substitute products owing to their preferences for specific features. Religions, color

tastes, and sizes are all examples. Sometimes products can touch an even deeper nerve,

triggering associations that relate to consumer identity as a community member.

Constructs, such as cultural distance, are rooted in the construct of Hofstede (1980).

Hofstede argued that the national level of culture comprises four cultural dimensions:

Individualism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, and masculinity. Moreover, in his later

research, Hofstede proposed the fifth dimension- long-term orientation. Most psychic distance

studies are based on the cultural dimensions of Hofstede (1983; 1991; 2001).

91

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

Therefore, based on the arguments supporting the construction of cultural distance based

on language, social norms and religions, this study hypothesizes that:

H1a: A positive association exists between cultural distance and location attractiveness.

2.3.2 Administrative distance or political distance

Historical and political associations shared by countries, preferential trading

arrangements, a common currency, and political union greatly affect trade among the

associations. The integration of the European Union is probably the most notable example of

a deliberate effort to diminish administrative and political distance among trading partners.

(Ghemawat, 2001)

Countries can also create administrative and political distance through unilateral

measures designed to protect domestic industries or natural resources or to ensure national

security. Individual government policies create the most common barriers to cross-border

competition, and include: tariffs, trade quotas, restrictions on foreign direct investment, and

preferences for domestic competitors in the form of subsidies and favoritism in regulation and

procurement.

Finally, weak institutional infrastructure of a target country can serve to dampen crossborder economic activity. Companies typically are reluctant to do business in countries with

corruption or social conflict problems. Eriksson et al. (1997) and Shrader et al. (2000) argued

that institutional differences increase the risk of international expansion.

Indeed, some studies suggest that conditions such as these depress trade and investment

far more than any explicit administrative policies or restrictions. However, countries with a

strong institutional infrastructure, for example a properly functioning legal system, are much

more attractive to outsiders.

More recently, researchers have argued in favor of the importance of considering

institutional distance between countries (Kostova, 1999; Kostova and Roth, 2002; Kostova

and Zaheer, 1999; Xu and Shenkar, 2002). Institutional distance is defined as the difference in

regulatory, cognitive, and normative aspects between the home and host countries (Kostova,

1999). Subramanian and Lawrence (1999) found that national locations remained distinctive.

Policy barriers at the borders, local cultural differences, and natural and geographical features

contribute to distinctiveness. This range of difference, together with incumbent ability to

maintain an advantage relative to outsiders (Buckley et al., 2002) and the first entrant benefits

enjoyed by local firms reinforced the differentiation of national economies. Thus hypothesis

H1b is presented below:

H1b: Attractiveness of the location increases with reducing administrative distance.

2.3.3 Geographic distance

Generally, the difficulty of conducting business in a country increases with geographic

distance from that country. However, geographic distance is not simply a matter of physical

distance. Other attributes that must be considered include the physical size of the country in

question, average within-country distances to borders, access to waterways and the ocean, and

topography. Man-made geographic attributes also must be considered, particularly

transportation and communications infrastructure.

Geographic attributes clearly influence transportation costs. Products with low value-toweight or bulk ratios, such as steel and cement, incur especially high costs with increasing

geographic distance. Likewise, the costs of transporting fragile or perishable products across

large distances are significant.

Besides physical products, intangible goods and services are also affected by geographic

distance. The level of information infrastructure, measured by telephone traffic and the

number of branches of multinational banks, explains much of the impact of physical distance

92

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

on cross-border equity flows. Major disparities in supply chains and distribution channels

represent a significant barrier to business. A recent study concluded that margins on

distribution within the United States— the costs of domestic transportation, wholesaling, and

retailing—on average act as a larger barrier to imports into the United States than

international transportation costs and tariffs combined.

In short, it is important to consider both information networks and transportation

infrastructures when assessing geographic influences on cross-border economic activity.

Similar to the arguments regarding differences in culture, administration, the above arguments

lead to the following hypothesis H1c:

H1c: A positive association exists between close geographic distance and location

attractiveness.

2.3.4 Economic distance

Economic distance indicates the difference between the economic conditions of the

individual foreign markets. Consumer wealth or income is the key economic attribute that

creates distance between countries, and exerts a significant effect on levels of trade and choice

of trading partners. Research suggests that rich countries, engage in more cross-border

economic activities relative to their economic size than do their poorer cousins. Most of these

activities involve other rich countries, as the positive correlation between per capita GDP and

trade flows obviously implies. However, poor countries also trade more with rich countries

than with other poor ones.

Of course, these patterns mask variations in the effects of economic disparities and in the

cost and quality of financial, human, and other resources. Evidence supporting the importance

of differences in economic conditions between the home market and host market can be found

in the literature on marketing and strategy. For example, in an export context Armine and

Cavusgil (1986) found that economic differences between markets positively influence the

degree of customization of marketing program elements. Moreover, Roth (1995) also found

that socioeconomic conditions in foreign markets influence the degree to pursuit of a common

brand image.

Observation of the importance of the economic differences between markets also exists in

companies that rely on economies of similarity to replicate their existing business models to

exploit their existing competitive advantages, and those companies whose competitive

advantage comes from economic arbitrage—the exploitation of cost and price differentials

from markets. Jain (1989) found that the economic similarity of market can reflect common

incomes and lifestyles. For example, similarities in income can influence strategies for

launching new products, setting price as well as marketing communication strategies

(Baalbaki and Malhirtra, 1992).

Whether they expand abroad for purposes of replication or arbitrage, we expect that, the

possibility of FDI should reduce with increasing economic differences between two markets.

Thus this study develops the following hypothesis:

H1d: A positive association exists between closer economic distance and (attractiveness

of location OR location attractiveness).

2.4 Top management background

Mangers from top management teams can impact firm strategic direction (Hambrick and

Finkelstein, 1995; Hambrick et al., 2005) and owing to their background (such as attributes

and experiences). Herrmann, and Datta (2005) argued that more internationally diversified

firms are likely to have top managers characterized with higher educational levels (Wiersema

and Bantel, 1992), shorter organizational tenures (Hambrick and Finkelstein, 1995; Datta and

Guthrie, 1994), younger executives (Datta and Rajagopalan, 1998), and more international

93

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

experience (Sambharya, 1996). Top executives with a “strong” background that is,

international experience) possess a better idea of how to operate in different nations (or areas),

as well as a “global mindset” that gives them more confidence in foreign environments and a

better ability to handle global competition (Tung and Miller,1990; Melin, 1992; Kedia and

Mukherji, 1999).

Besides, many empirical studies on executive demographic characteristics and strategic

choice have been based on the upper echelon theory devised by Hambrick and Mason (1984).

Psychological factors and location choice have rarely been studied directly in studies of top

management. The background characteristics and experiences of managers shape their

cognitive perspective and knowledge bases, reflecting their underlying psychological

orientation (Kiesler and Sproull, 1982).

In theory, psychic distance is a combination of national, organizational and individual

level factors. Moreover, experience mainly exerts an influence at the individual level, and

thus experience can be a powerful determinant of psychic distance. As operations come to

encompass more distant countries and international experience grows, psychic distance is

predicted to reduce (Gripsrud, 1990; Benito and Gripsrud, 1992; Johason and Vahlne, 1977).

Knowledge of foreign markets is important in overcoming the “psychic distance” of doing

business overseas (Melin, 1992). Sambharya (1996) also argued that international experience

among top management is associated with reduced uncertainty regarding international

operations. This involvement in increasingly distant markets requires considerable learning

efforts, which increase with growing psychic distance to the target market.

Differences in the cognitive perspectives of managers influence all aspects of the strategic

decision-making process. Location choice is definitely a crucial strategic choice in

internationalization. Thus, this study expected to find a moderator effect on the relationship

between psychic distance and location selection decision for three reasons: First,

contemporary multinational enterprises (MNEs) frequently yield the most complex

managerial decision-making environment (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1992; Sanders and Carpenter,

1998). This global complexity is likely to make mangers with international assignment

experience invaluable for many MNCs (Daily et al., 2000; Gregersen et al., 1998; Maruca,

1994). Second, mangers of MNEs are more aware of cultural differences today than they were

20 years ago. Owing to their education and increased knowledge obtained from the media and

communication technologies, modern mangers may be more comfortable than their

predecessors with diversifying into countries with dissimilar cultures (Tihanyi et al., 2005).

Third, Brouthers and Brouthers (2003) argued that US MNE managers are more risk averse in

making their entry mode decisions than their counterparts in other developed countries. This

implies that managerial characteristics create the difference. Manager background thus

matters (Carpenter et al., 2000).

From the above, it can be concluded that the impact on the relationship between psychic

distance and location choices reduces with managerial experience. Furthermore, due to

changing individual experience, particularly foreign experience, psychic distance has

gradually reduced. From this perspective, hypothesis 2 can also be proposed:

H2: The influence of psychic distance affect on location attractiveness reduces with top

management background in FDI.

3. Research design

Hofstede’s national culture distance scale was obtained for each country for the period

from 1968 to 1972. Given the sociological and political changes during these three decades it

is inconceivable for the scores to have remained stable, whilst Ghemawat(2001) argued

distance still matter and the factors beyond culture.

94

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

Moreover, the cultural component of psychic distance generally utilizes national

boundaries, when there are the substantial regional or industry cultural variations (namely,

retail). ‘True distance’ for a particular location (namely, industrial cluster) must take into

account the perceptions, understanding, and experience of firm management team.

China is a large and diverse enough country to have subnational-level differences, and has

enjoyed high, sustained growth rates for the past two decades. China has average annual

economic growth of around 10 percent since 1978. Meanwhile, in the coastal regions the

average growth rate has been about 12 percent. The growth of China is widely believed to be

at least partly due to heavy foreign direct investment (FDI). In fact, among developing

countries, China is now the largest recipient of FDI in the world. Given the important role of

FDI in China’s growth, it is critical to examine further the characteristics of FDI in China.

This study uses the example of FDI in China by Taiwanese firms to demonstrate the CAGE

model because of the close links between Taiwan and China. Specifically, it is believed that

Taiwanese have a good understanding of regional differences within China (including,

language, social norms, beliefs, government systems, and so on). Thus the Taiwanese

example is helpful in distinguishing cultural, administrative, geographic and economic

differences a the subnational-level. This study focused on subnational-level location choice

because of its increasing quantitative and competitive performance for business strategies.

3.1 Data collection

To test the seven hypotheses proposed in this study, the approach of collecting firm-level

data and then performing empirical analysis using factor analysis and logistic regression was

applied. The data was gathered using mail surveys and personal interviews.

From the List of Taiwanese Companies in China (Digitimes,2004), issued by the Chinese

National Federation of Industries, 1,200 industrial manufacturing firms were selected as

targets for mailing a survey. These firms were selected on the basis of size ($20-200 million

in sales), and ownership (wholly owned). Questionnaires were mailed directly to top

management (Chairman, CEO, President, Vice President; cf. Michel and Hambrick, 1992).

A total of 286 of 1200 (23.9%) questionnaires were returned, of which 18 were eliminated

owing to incomplete questionnaires and data problems. The effective sample size thus was

258, representing a final response rate of 21.5% (258/1200).

3.2 Measures

Based on a review of the previous academic and psychology literature, this study designed

measures for the constructs being studied. Certain measures were adapted from previous

research, whereas other measures were developed especially for this investigation. The initial

questionnaire was based upon a pre-test of 50 top management personnel from international

businesses in Taiwan.

3.3 Independent variables

Psychic Distance. Psychic distance is generally measured by measuring cultural distance

based on Hofstede's (1983, 2001) definitions and descriptions of the five dimensions. This

study used new measures, inspired by Pankaj Ghemawat (2001) for cultural attributes,

administrative attributes (e.g. legal and political environments), geographic differences, and

economic environment. Since no scale for CAGE distance framework was available in the

literature, an attempt was made to generate items that tapped the domain of each construct

recommended by Churchill (1979). Accordingly, a battery of 17 items was developed and

categorized into four types. Notably, during the development of the research instrument,

questions on colonial ties, monetary or political association and social norms were avoided

due to the reality of the cross-strait situation and to avoid emotional responses for defending a

95

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

political stand. This investigation also found cost and quality of information and knowledge

was not a good determinant for distinguishing economic distance, and thus these two items

were deleted too. Respondents were asked to indicate the degree to which the foreign market

was similar to or different from the home market using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from (1)

identical to (6) totally different.

A composite index of cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic distance was

designed and served as the basis for the psychic distance construct. This index was based on

Kogut and Singh's (1988) formula for cultural distance. The index is represented algebraically

as:

n

{

}

CDj = ∑ (Iij −1)2 /Vi /n

I−1

where CD j , AD j , GD j or ED j are the cultural , administrative, geographic, or economic

differences of the j th foreign market from the home market; I ij denotes the index of the i th

cultural , administrative, geographic, or economic dimensions and the j th market, 1

represents the home market and Vi is the variance of the index of the i th dimension(Kogut

and Singh's ,1988). These two indices were then averaged to provide a composite index of

psychic distance, which was calculated for both close and distant markets.

3.4 Moderating Variable

Top management background. Three items were applied for the measurement: foreign

experience, local operation experience (business practice), and sufficiency of information.

These three items were measured using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly

disagree to (6) strongly agree.

3.5 Control variables

This study also included two control variables (age and company size) that might affect

the hypothesized relationships. International business scholars have identified age and firm

size as important control variables (Burgel and Murray, 2000; Zahra et al., 2000; Shrader et

al., 2000)

Tenure. Older top management are likely to have more network relationships, providing

more exposure to strategic decisions and greater ability to accumulate resources. Age of

management is a positive force to internationalization (Burgel and Murray, 2000). Tenure was

used as a proxy for actual age.

Firm size. Larger firms enjoy access to more resources]. Since the coordination of home

base and foreign sub-unit can be highly demanding and require a critical mass of employees

and managers, larger firms should be better equipped to handle this contingency, and thus

have provided significant funding for other studies of internationalization. (Bloodgood et

al.,1996; Steensma et al., 2000). Firm size is typically operationalized either through number

of employees or total sales. Since the two aspects must be scaled carefully, this study use the

firm size recognized by the respondent] as the control for company size.

3.6 Dependent variables

Location choice. This work selected 30 locations (cities in China) for respondents to

choose from. Respondents were asked to identify the most favorable location for measuring

their psychic distance and they were also asked to mark the locations where their firm had

already invested (multiple). The measurement for Location choice is a dichotomous variable

96

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

used to indicate whether the firm has been investing in the location. The hypothetical factors

were related] using the following logistic model:

P (Yi = 1) =

1

1 + exp(−α − X i β )

The dependent variable is:

1 , if a firm had been investing in the location

Those firms that had

Yi = ⎧⎨

⎩0 , otherwise

invested in the location were assigned the code 1, while other firms were assigned the code 0.

4. Analysis and results

The analysis begins by calculating descriptive statistics for the summed scales. Person

correlations between each summed scale also were calculated and are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

CAGE

CD

AD

GD

ED

TM_B

LI

FE

LWE

Tenure

SIZE

Mean

3.758

3.625

3.399

3.605

4.403

4.390

2.564

2.398

2.361

5.089

1.472

S.D.

0.670

1.006

1.005

1.050

0.796

0.916

0.570

0.630

0.684

1.388

0.500

CAGE

--

0.732**

0.646**

0.737**

0.653**

-0.050

-0.115

0.035

0.005

-0.126*

-0.006

--

0.284**

0.425**

0.281**

0.040

-0.011

0.034

0.078

-0.111

0.073

--

0.205**

0.284**

-0.035

-0.110

0.097

-0.030

-0.009

-0.037

--

0.366**

-0.119

-0.138*

-0.040

-0.057

-0.137*

-0.034

ED

-0.020

-0.052

0.005

0.030

-0.091

-0.020

TM_B

--

0.681**

0.698**

0.746**

0.204**

0.189*

--

0.346**

0.438**

0.079

0.197*

--

0.432**

0.160**

0.130*

--

0.156*

0.126*

--

0.090

CA

AD

GD

Li

FE

LWE

Tenure

SIZE

--

Notes: p < 0.05 , ** p < 0.01

CAGE = CAGE distance ; CD = Cultural distance; AD = administrative distance; GD = geographic distance;

ED = economic distance; TM_B = top management background; LI = local information; FE = foreign perience;

LWE = local working experience;SIZE = firm size

4.1 Reliabilities and validation

The scale reliability met the recommendation of Nunally (1978) since the Cronbach

exceeded 0.7 for all of the constructs except administrative distance. Discriminant validity

addresses the degree to which measures of different variables are unique (Bagozzi, 1982).

This is achieved when correlations between any two latent variables are found to be

significantly different from unity, i. e. significantly less than 1.00 (Bagozzi, 1982; Segars and

Grover, 1998). Correlations among CD, AD, GD and ED are listed in Table 3. The confidence

intervals of the correlations show that the values were significantly less than unity (1.00), thus

confirming discriminant validity.

97

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

4.2 Factor analysis

Table 4 lists factor analysis for psychic distance. The four factors that were loaded

corresponded to cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic distances. Although not

perfect, this result is almost identical to the concept of Ghemawat (KMO = 0.851; Bartlett’s

Test of Sphericity =1255.053, p < 0.000).

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were performed, and all items were

significantly loaded onto the hypothesized constructs. All survey measures were based on a

six-point scale, and both semantic differential and agree-disagree scales were used.

Table 4. Factor analysis of psychic distance

factor1

Language

Religions

Political hostility

Government policies

Common border

Sea or river access

Transportation and communication

Climate

Consumer income

Cost and quality of natural resources

Cost and quality of financial resources

Cost and quality of human resources

Cost and quality of infrastructure

Eigen value

Accumulated explained variation

Accumulated explained variation (%)

factor2

.115

.283

7.108E-02 .114

.321

.246

.657E-02

.158

.793

.160

.132

.831

.234

.640

3.883E-02 .682

.283

.730

.103

.794

5.499E-02

.833

7.358E-02

.782

.113

.768

4.787

1.991

36.822

15.315

36.822

52.137

factor 3

5.485E-03

.182

.724

.831

.200

factor 4

.836

.882

5.840E-02

.123

.154

-.179

.113

.342

9.579E-02

.302

.197

.133

-3.064E-02

.114

6.250E-02

9.665E-02 9.714E-02

.255

3.265E-02

1.853E-02

.123

1.144

1.089

8.798

8.379

60.935

69.314

This investigation contained a single dichotomous dependent variable (Location Choice),

with Psychic Distance comprising four different distances (Cultural Distance, Administrative

distance, Geographic Distance, and Economic Distance). This study thus used multinomial

logistic regression for the hypothesis testing (Sharma, 1981).

Table 5 lists the regression model results, using the Top Management responses on

measures of Location choice as dependent variables. The average difference in responses to

Psychic Distance measures is a significant and negative (-0.558, p < 0.01) beta parameter in

the CAGE model. Thus, H1 is accepted. The average difference in responses to cultural

distance measures is an insignificant beta parameter in the CAGE model, as does the

economic distance. Thus, H1a and H1d are rejected.

Administrative Distance and Geographic Distance have a significant and negative

parameter (-0.403, p < 0.001; -0.272. p < 0.05) in the Logit regression model. Thus, H1b and

H1c are accepted.

98

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

Table 5. Logit regression results

Wald value

Psychic distance

Cultural distance

Administrative Distance

Geographic distance

Economics distance

6.863

2.038

8.073

4.119

0.603

Β value

-0.558**

-0.193

-0.403**

-0.272*

-0.135

Notes: * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

To further improve understanding, this study used three hypothesized independent

variables (foreign experience, local information, and local working experience) and four

control variables (firm size, industry, party, and tenure). This study thus used a t-test, the

results of which are listed in Table 6.

Table 6. Logistic regression results

Dependent variable: Location choice (dichotomous)

model 1

model 2

model 3

model 4

Distance

-0.647**

(0.265)

CAGE distance

Top management

background

-0.643*

(0.269)

1.658

(1.150)

0.236

(0.162)

2.337*

(1.049)

-0.554*

(0.271)

CAGE*top management

background

Control variables

Firm size

-0.709*

(0.331)

-0.793*

(0.339)

-0.735*

(0.343)

0.709*

0.347)

Industry

0.106

(0.069)

0.072

(0.071)

0.084

(0.072)

0.056

(0.074)

Political party

-0.362*

(0.181)

-0.351*

(0.182)

-0.343*

(0.182)

-0.286

(0.184)

Tenure

0.076

(0.093)

0.034

(0.096)

0.009

(0.098)

-0.001

(0.099)

-2 (log-likelihood)

Cox & Snell R2

244.7

0.082

238.5

0.107

236.4

0.116

232.0

0.133

Notes: * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

5. Discussion of results

The findings of this investigation have broadened and deepened our understanding of how

perceived distance affects top management location choice, and top management background

can moderate the relationships between psychic distance and location choice. This

99

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

investigation introduced a detailed model of Psychic Distance and Location Choice that

differs from previous research in several ways.

First, this investigation proposed that location choice is influenced by the psychic distance

as conceived by top management. Often an ideal condition for a firm’s location choice is to

increase firm productivity by utilizing the presents of location advantages related to

substantial spatial concentrations (agglomerations). These substantial spatial concentrations

are variously called, depending on geographic scale, clusters, industrial districts, or regions.

However, location choice is not rational, and is affected by the mind, behavior, and

experience of the one making the decision. Additionally, firms must be able to interact

effectively within a locale to learn, connect, and leverage local resources. Thus, factors that

affect these interactions are critical in understanding the suitability of location choice.

Consistent with the literature, this study focused on differences in Psychic Distance as

factors that affect on such interaction. Previous measures of psychic distance were based on

Hofstede's (1983) definitions and descriptions of the five dimensions of national culture. The

measurement items captured general aspects of national values and attitudes, and were

adapted to capture perceived differences between the home country of the respondent and a

foreign country. New measures were developed, based on a review of the literature on

international business and new economics geography, for the culture, legal and political

environment, geographic environment, and economic environment. Building on the findings

of Ghemawat (2001) , this study argued that the potential disruptiveness of differences in

Psychic Distance on location choice increases with their relevance to that choice. Thus

differences in culture, administrative, geographic and economic distance, and not merely

differences in cultural distance must be assessed. The empirical results indicate that CAGE

distance is negatively related to the tendency of particular location choice.

Second, using Taiwanese firms in China as an example provides insight into the

subnational-level. The special links between Taiwan and China make the observation of

administrative, and geographic distance easier, the findings regarding administrative distance

are consistent with the argument of Subramanian and Lawrence (1999), and the meaningful

findings regarding geographic difference suggest that geography still matters (Ghemawat,

2001). Moreover, the importance of new geographic factors was attested to by the concern

regarding ‘the new geography of competition’ in mobile investment (Raines, 2003). The

observations of this study found no evidence that cultural difference affects location decision.

O’Grady and Lane (1996) also found that many Canadian retail companies did not succeed in

the culturally close environment of the USA. They concluded that a ‘psychic distance

paradox’ exists] because assumptions of cultural similarity can prevent managers from

learning about critical differences. This study believes that this phenomenon is consistent with

the findings of O’grady and Lane (1996). An alternative explanation may be that Taiwanese

are familiar with China Culture since that is the source of most Taiwanese culture), and thus

also have a good understanding of regional variations in Chinese culture. There are

possibilities of feeling no difference in local culture.

Confirming the findings of Hewett et al. (2003), the hypothetical relationship of economic

distance and location choice is not supported. Regarding economic conditions, findings from

other studies appear to differ according to the manner in which individual market conditions

were considered. For example, Ghemawat (2001) argued that MNEs expand overseas for

purposes of replication or arbitrage. When arbitrage is the driver, the greater the difference the

better, while when replication is the driver, the smaller the difference the better. Therefore,

this study speculated that the relationship curve may comprise a “U” shape. However, this

study was unsure about whether longer economic distance would increase firm satisfaction

with the location due to more economic benefits, or whether shorter economic distance would

provide greater location satisfaction because of similarities in the business practices and

100

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

economic status quo of the countries involved (Linder, 1961). Various interpretations are

possible. This ambiguity may be the main reason that not all hypotheses were supported.

However, this study believes that the proposed model offers valuable new insights for

international businesses regarding location choice. Meanwhile, we also felt that the proposed

model presents implications for other contexts in which differences in psychic distance were

believed to be strongly and negatively impact firm satisfaction with location.

Third, the observation that top management background moderates the relationship

between perceived distance and location choice is particularly noteworthy.

Considering the interaction with top management background, the perceived distance was

observed to be “contingent” meaning that the CAGE distance maintains some degree of

negative relationship with location choice. However, cage distance develops a positive

relationship with location choice when top management background exceeds some degree. In

practice, mangers with abundant experience of international processes or rich in local things

(system, working experience, network, information) would be more “respect” local difference.

The contingency of cage distance provides a new method of treating the role of top

management background as local things.

Fourth, foreign firms located in the host country may attract other foreign firms

participating in the same supply chain. For instance, Florida and Kenney (1994) found that

Japanese investment in research and development in the U.S. tended to be clustered in the

Midwest automotive region and around technologically advanced areas. FDI provides not

only capital but also technology and management know-how necessary host economy firms.

Evidence also exists of a positive correlation between FDI inflows and host country economic

growth via the spillover effects from advanced technology (Borenzstein et al., 1998). It

remains uncertain whether supply chain attractiveness or technology spillover affect or

interact with the location decision from the psychic distance perspective.

6. Limitations and conclusions

The scores of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions were obtained for each country for the

period 1968 to 1972. Given the major social and political changes during this period it is

inconceivable that the scores could have remained stable. The key question examined in this

study is whether psychic distances influence CEO decision on location choice. This study

proposes that psychic distance does matter to CEOs.

Aspects of the strategy of MNEs can also be enhanced by a deeper understanding of

spatial issues. Geographical models can illuminate strategic decisions both through the use of

models (Storper, 2001) and also empirically (Wrigley, 2000; Wrigley and Coe, 2005). Local

labor markets, which are a key attraction for efficiency-seeking FDI, are also geographically

configured; and the analysis presented here] benefits from the insights associated with

economic geography (Hanson, 2000). As noted above, MNE strategy cannot be fully

comprehended without understanding the role played by psychic distance in choice of

location.

However, the model generalizability is limited to situations involving group decision

making. Thus, the model cannot also be applied to team leadership in situation focused on

compromise or to more rational decision making processes.

When entering an under-developed market, a different set of mindset is required,

compared to when entering a developed or developing markets. Cho et al., (2005) suggested

three selecting mechanisms that are needed to enter an under-developed market for FDI while

seeking competitive advantages which bring us the awareness of different country

development may alert different result of this study. Besides, Along with the concept of

network theory, Tseng (2005) argued the interaction among members of the industrial

101

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

network and the modes of foreign direct investment may impact the psychic distance which

did not debate with this study.

Clearly, an important subsequent step in this line of research is to investigate the

organizational culture of the model developed in this study. Despite significant progress in

research on the economic geography of globalization, enormous opportunity still exists for

further development and innovation. One such area is the geography of culture (Thrift, 2000)

where international business scholars drawing on their long tradition of work in this area

(Hofstede,1980; Ronen and Shenkar, 1985) and potentially have an enormous amount to

contribute. These organizational cultures are of enormous practical and theoretical interest,

particularly in relation to their alignment or non-alignment with national, linguistic, and other

frontiers (Shenkar, 2001).

References

Armine, L.S., Cavusgil, S.T. (1986) Consumer market environment in the Middle East. In

Kaynak, E. (Ed.) International Business in the Middle East. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin.

pp.163-176.

Baalbaki, I.B., Malhotra, N.K. (1992) Marketing management bases for international market

segmentation: An alternate look at the standardization/customization debate. International

Marketing Review, 10(1), 19-44.

Bartlett, C.A., Ghoshal, S. (1992) What is a global manager? Harvard Business Review, 70(5),

124-133.

Bagozzi, R.P., Fornell, C. (1982) Theoretical concepts, measurements, and meaning. In

Fornell, C. (Eds) A Second Generation of Multivariate Analysis. Praeger, New York, NY,

Vol. 1, 24-38.

Beckermann, W. (1956) Distance and the pattern of intra-European trade. Review of

Economics and Statistics, 38(1), 31-40.

Benito, G.R.G., Gripstud, G. (1992) The expansion of foreign direct investments: Discrete

rational location choices or a cultural learning process? Journal of International Business

Studies, 23 (3), 461-476.

Bilkey, W.J., Tesar, G. (1977) The export behavior of smaller-sized Wisconsin manufacturing

firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 93-99.

Bloodgood, J.M., Sapienza, H.J., Almeida, J.G. (1996) The internationalization of new highpotential U.S. ventures: Antecedents and outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,

20(4), 61-76.

Brouthers, K.D., Brouthers, L.E. (2003) Why service and manufacturing entry mode choices

differ: the influence of transaction factors, risk and trust. Journal of Management Studies,

40(5), 1179-1204.

Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., Lee, J.W. (1998) How Does Foreign Direct Investment

Affect Economic Growth?, Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115-135.

Burgel, O., Murray, G.C. (2000) The international market entry choices of start-up companies

in high-technology industries. Journal of International Marketing, 8(2), 33-62.

Buckley, P.J., Clegg, J., Wang, C.Q. (2002). The impact of inward FDI on the performance of

Chinese manufacturing firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 33 (4), 637-665.

Cairncross, F. (1997) Down with distance. The Economist, 344(8034), T21-24.

Carlson, S. (1975) How Foreign is Foreign Trade? A Problem in International Business

Research. Studia Oeconomiae Negotiorum. Uppsala University, Uppsala.

Carpenter, M.A., Sanders, W.G., Gregersen, H.B. (2000) International assignment experience

at the top can make a bottom-line difference. Human Resource Management, 39(2/3),

277-286.

102

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

Child, J., Ng, S.H., Wong, C. (2002) Psychic distance and internationalization: Evidence from

Hong Kong firms. International Studies of Management & Organization, 32(1), 36-58.

Cho, D.S., Lee, Y.C., Yang, J.Y. (2005) Three mechanisms to enter under-developed markets:

The case of investment in Mongolian market by Korean firms. Asia Pacific Management

Review, 10(5), 341-347.

Churchill, G.A. (1979) A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs.

Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64-73.

Clark, T., Pugh, D. (2000) Similarities and differences in European conceptions of human

resource management. International Studies of Management & Organization. White Plains:

Winter 1999/2000. 29(4), 84-101.

Coughlin, C.C., Terza, J.V., Arromdee, V. (1991) State characteristics and the location of

foreign direct investment within the United States. The Review of Economics and

Statistics, 73(4), 675-684.

Datta, D.K., Guthrie, J.P. (1994) Executive succession: Organizational antecedents of CEO

characteristics. Strategic Management Journal, 15(7),569-578.

Datta, D.K., Rajagopalan, N. (1998) Industry structure and CEO characteristics: An empirical

study of succession events. Strategic Management Journal, 19(9), 833-852.

Daily, C.M., Certo, S.T., Dalton, D.R. (2000) International experience in the executive suite:

The path to prosperity? Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 515-523.

Digitimes (2004) List of Taiwanese Companies in China. Digitimes,Taiwan.

Evans, J., Mavondo, F.T. (2002) Psychic distance and performance: An empirical

examination of international retailing operations. Journal of International Business Studies,

33(3), 515-532.

Eriksson, K., Johanson, J., Majkgard, A., Sharma, D.D. (1997) Experiential knowledge and

cost in the internationalization process. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(2),

337-360.

Florida, R., Kenney, M. (1994) The globalization of Japanese R&D: The economic geography

of Japanese R&D investment in the United States. Economic Geography, 70(4), 344-369.

Ghemawat, P. (2001) Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard

Business Review, 79(8), 137-147.

Gong, H. (1995) Spatial patterns of foreign direct investment in China’s cities, 1980-1989.

Urban Geography, 16(3), 198-209.

Gregersen, H.B., Morrison, A.J., Black, J.S. (1998) Developing Leaders for the Global

Frontier. Sloan Management Review, 40(1),21-32.

Gripsrud, G. (1990) The determinants of export decisions and attitudes to a distant market:

Norwegian fishery exports to Japan. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(3), 469485.

Hambrick, D.C., Mason, P.A. (1984) Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its

top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193-207.

Hambrick, D.C., Finkelstein, S. (1995) The effects of ownership structure on conditions at the

top: The case of CEO pay raises. Strategic Management Journal, 16(3), 175-194.

Hambrick, D.C., Finkelstein, F., Mooney, A.C. (2005) Executive job demands: New insights

for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviours. Academy of Management

Review, 30(3), 472-491.

Hanson, S. (2000) Jobs and economic development: Strategies and practice. Economic

Geography, 76(2), 196-198.

Head, K., Ries, J. (1996) Inter-city competition for foreign investment: Static and dynamic

effect of China incentive area. Journal of Urban Economics, 40(1), 38-60.

103

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

Head, K., Ries, J., Swenson, D. (1995) Agglomeration benefit and location choice: Evidence

from Japanese manufacturing investment in the United States. Journal of International

Economics, 38(3/4), 223-247.

Herrmann, P., Datta, D.K. (2005) Relationships between top management team characteristics

and international diversification: An empirical investigation. British Journal of

Management, 16(1), 69-78.

Hewett, K., Roth, M.S., Roth, K. (2003) Conditions influencing headquarters and foreign

subsidiary roles in marketing activities and their effect on performance. Journal of

International Business Studies, 34( 6), 567-585.

Hofstede, G. (1980) Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply

abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1), 42-63.

Hofstede, G. (1983) National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural

differences among nations. International Studies of Management and Organization, XIII

(1-2), 46-74.

Hofstede, G. (1983) The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of

International Business Studies, 14(2), 75–89.

Hofstede, G. (2001) Culture’s Consequences. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA.

Jain, S.C. (1989) Standardization of international marketing strategy: Some research

hypotheses. Journal of Marketing, 53(1), 70-79.

Johanson, J., Wiedersheim-Paul, F. (1975) The internationalization of the firm–Four Swedish

cases. Journal of Management Studies, 12(3), 305-322.

Johanson, J., Vahlne, J.E. (1977), The internationalization process of the firm - A model of

knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of

International Business Studies, 8(1), 23-32.

Kedia, B.L., Mukherji. A. (1999) Global managers: Developing a mindset for global

competitiveness. Journal of World Business, 34(3), 230-251.

Kiesler, S., Sproull, L. (1982) .Managerial response to changing environments: perspectives

on problem sensing from social cognition. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(4), 548570

Kogut, B., Singh, H. (1988) The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode.

Journal of International Business Studies, 19(3), 411-432.

Kostova, T. (1999) Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: A contextual

perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24(22), 308-324.

Kostova, T., Roth, K. (2002). Adoption of an organizational practice by subsidiaries of

multinational corporations: Institutional and relational effects. Academy of Management

Journal, 45(1), 215–233.

Kostova, T., Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity:

The case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 24(11), 64-81.

Lee, D.J. (1998) Developing international strategic alliances between exporters and importers:

The case of Australian exporters. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 15(4),

335-349.

Levinson, A. (1996) Environmental regulations and manufacturers' location choices:

Evidence from the census of manufactures. Journal of Public Economics, 62(1/2), 5-29.

Linder, S.B.(1961) An Essay on Trade and Transformation. Wiley, New York.

Luostarinen, R. (1980) Internationalization of the Firm. Helsinki School of Economics:

Helsinki, Finland.

Maruca, R.Z. (1994) The right way to go global: An interview with Whirlpool CEO David

Whitwam. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 134-155.

McEvily, B., Zaheer, A. (1999) Bridging ties: A source of firm heterogeneity in competitive

capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 20(12), 1133-1157.

104

C.-L. Kuo, W.-C. Fang / Asia Pacific Management Review 14(1) (2009) 85-106

Melin, L. (1992) Internationalization as a strategy process. Strategic Management Journal,

13(Winter) , 99-118.

Michel, J. G., Hambrick, D.C. (1992) Diversification position and top management team

characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 35(1), 9-38.

Nachum, L. (2000) Economic geography and the location of TNCs: Financial and

professional service FDI to the USA. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(3),

367-386.

Nohria, N., Carlos, G.-P. (1991) Global Strategic Linkages and Industry Structure. Strategic

Management Journal, 12 ,105-125.

Nordstrom, K., Vahlne, J. (1994) Is the globe shrinking? Psychic distance and the

establishment of Swedish sales subsidiaries during the last 100 years. In Landeck, M. (Ed.)

InternationalTtrade: Regional and Global Issues. St. Martin's Press, United States.

Nunally, J.C. (1978) Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill, New York.

O'Grady, S., Lane, H. (1996) The psychic distance paradox. Journal of International Business

Studies, 27(2), 309-333.

Porter, M.E. (1990) The Competitiveness of Global Industries. The Free Press, New York.

Porter, M.E. (1998) Location, clusters, and the “new” micro economics of competition.

Business Economics, 33(1), 7-13.

Porter, M.E. (2003) The economic performance of regions. Regional Studies, 37(6 & 7), 549–

578.

Raines, P. (2003) Cluster behaviour and economic development: New challenges in policy

evaluation. International Journal of Technology Management, 26(2,3,4), 191-204.

Ronen, S., Shenkar, O. (1985) Clustering countries on attitudinal dimensions: A review and

synthesis. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 435-454.

Roth M.S. (1995) Effect of global market conditions on brand image customization and brand

performance. Journal of Advertising, 24(4), 55-75.

Sambharya, R.B. (1996) Foreign experience of top management teams and international

diversification strategies of U.S. multinational corporations. Strategic Management

Journal, 17(9), 739-746.

Sanders, W.G., Mason, A., Carpenter, M.A. (1998) Internationalization and firm governance:

The roles of CEO compensation, top team composition, and board structure. Academy of

Management Journal, 41(2),158-178.

Segars, A.H., Grover, V. (1998) Strategic information systems planning success: An

investigation of the construct and its measurement. MIS Quarterly, 22(2), 139-163.

Sharma, S. (1981) The Theory of Stochastic Preferences: Further comments and clarifications.

Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 364-369.

Shaver, M.J. (1998) Do foreign-owned and US-owned establishments exhibit the same

location pattern . Journal of international business studies, 29(3), 469-492.

Shenkar, O. (2001) Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization

and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3),

519-533.

Shrader, R.C., Oviatt, B.M., McDougall, P.P. (2000) How new ventures exploit trade-offs

among international risk factors: Lessons for the accelerated internationization of the 21st

century. Academy of Management Journal, 43(6),1227-1247.

Sousa, C., Bradley, F. (2005) Global markets: does psychic distance matter? Journal of

Strategic Marketing, 13(1), 43-59.

Steensma, H.K., Marino, L., Weaver, K.M., Dickson, P.H. (2000) The influence of national

culture on the formation of technology alliances by entrepreneurial firms. Academy of