1 10. Monopoly In this chapter you will learn: Reasons for the

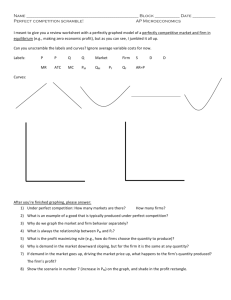

advertisement

1 10. Monopoly In this chapter you will learn: Reasons for the existence of monopoly; Product differentiation and brand loyalty - downward sloping demand; Monopoly pricing; How monopolists restrict output to raise price; How a monopolist can pass along a cost increase to consumers and why it can’t; Problems with monopoly; How monopolists price discriminate; How monopolists use their market power: Tying, Bundling; About cartels and why they are so unstable. 10.1 Introduction Under competition, the commodity is homogeneous in the sense that a consumer has difficulty telling one firm's product from another firm's, information flows relatively quickly across the participants of the market, and no one has any market power, e.g., price is determined in the marketplace. If the price is lower at another firm, consumers will buy from that firm. This forces other firms to get their price down and this forces them to be as efficient as possible. Some firms will survive this competitive pressure, while others will not. We can think of the model of perfect competition as a benchmark case that we can use as a starting point for a richer analysis. The model of competition helps us make predictions about how a market might respond to an external influence, e.g., change in income, and many times the predictions tend to hold up pretty well. We can also develop richer, more detailed models to explain behavior that is more complicated. For example, we started deregulating the airline industry in the late 1970s. It was known that there were economic profits being made prior to deregulation. Our model of competition predicts that entry will occur in such an industry and that is exactly what happened. Just before deregulation there were 11 airline companies in the industry. We began to deregulate the business side of the industry and by the late 1980s there were over thirty companies competing. So our model of competition can explain this behavior. Some markets are characterized by special circumstances where the model of competition does not apply. We need another model to help us understand how the market works when the model of competition does not apply. Perfect competition where no one has market power is one extreme case. At the other extreme is the case of monopoly where the market is characterized by literally one firm with extraordinary market power. Such a firm will not behave as our model of competition predicts and it is to that situation we now turn. A case in point is the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA), which retained its monopoly over aluminum production for fifty years.1 It received a patent in the late 1880s for a process that extracts oxygen from bauxite to produce aluminum. Three years before the patent ran out it patented a more efficient process in 1903. ALCOA signed long term agreements with owners of bauxite deposits so only they could receive supplies of bauxite, no other American company could. In addition, ALCOA signed a contract with foreign producers not to invade one another's markets. These various contracts were challenged in court by other firms that wanted to enter the lucrative business of producing aluminum and they were invalidated in 1912. However, ALOCA had such a head start it was difficult for its competitors to catch up. Every time a new company tried to enter the industry, ALOCA flooded the market with cheap aluminum keeping 1 http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/Portal/Communities/BHP/MPDFs/Historic_Aluminum_Resources_of_Southwestern _PA.pdf 2 the competition out. After World War Two the government sold its aluminum processing plants to two companies, Reynolds Metals and Kaiser, thus ending ALCOA's monopoly. A more modern example of monopoly is Microsoft in the 1990s and early 2000s. In the 1990s their operating system was used in approximately 95% of all desktop computers sold in the United States and they had about 75% of the applied software market. There was only token competition from Apple's Macintosh OS X Panther system, and independent systems like Linux. The operating system is a set of instructions that guide the basic functions of the computer, e.g., the point and click system of opening a file. All other software programs have to "plug into" the operating system in order to work and software developers have to make sure their software is compatible with the system. And a program that is compatible with one system will not be compatible with another. So owning the operating system gives the owner a great deal of power and control over the market. Without the operating system, the computer would be like a stone perched on your desk, brooding Zen-like. Microsoft tried to use its control of the operating system to force Netscape, one of its main competitors in the "browser" market, out of business. The courts ruled that during the so-called "browser wars" of the late '90s, Microsoft took illegal actions that were part of a broad strategy to specifically drive Netscape out of business so Microsoft could completely control the browser market as a monopoly.2 In 2003 the European Commission began considering charges against Microsoft for anti-trust violations of European laws. In 2013 a preliminary judgment went against Microsoft and they are to be fined $732 million for their actions.3 In the 2000s Apple increased its market share dramatically with the introduction of its G5 duel Intel processor desktop computers, a laptop that is more powerful than the PC Windows system, the MacBook "Air," advertised as the lightest, thinnest laptop available at the time, and its iPod, iPhone, and iPad. At the same time Microsoft introduced Vista, its much anticipated, new operating system. Unfortunately, it is riddled with all kinds of problems. Even the top executives at Microsoft won't use it. The near monopoly created by Microsoft has been overtaken by new competition from Apple and Samsung, among others.4 This provides a general rule. Whenever there are unusual profits created by a monopolist, other firms will attempt to compete for those profits and the monopoly won't last long. There are only a few exception. However, clearly, such companies as ALOCA, Microsoft, AT&T, XEROX, and Kodak will not behave as a firm would under perfect competition. We need to develop a new model to explain and understand their behavior. It is, however, closely related to our model of competition.5 We will assume, for example, that the monopolist tries to maximize profit, just as 2 Ironically, they were caught when the Justice Department investigators uncovered "deleted" emails sent among some of the top executives of Microsoft who thought they had destroyed the evidence by deleting the emails. Apparently, "delete" for Microsoft programmers doesn't mean "extinguish completely," but instead means "place out of the user's sight and maintain a permanent magnetic image of the file in an obscure folder on the hard drive for the Justice Department to find in the event of an investigation." See http://www.nethistory.info/History%20of%20the%20Internet/browserwars.html By 2014 observers of the industry were declaring Microsoft an ultimate loser in the browser wars. See http://www.computerworld.com/article/2475037/microsoft-windows/it-s-over----internet-explorer-won-thebrowser-war--does-it-matter-.html 3 http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/07/technology/eu-fines-microsoft-over-browser.html 4 In terms of market share Apple has 46%, Android 36%, Microsoft 11%, and the rest is carved up among 4 or 5 smaller competitors. See http://www.macobserver.com/tmo/article/gartner_projects_apple_to_rule_tablet_market_through_2015 5 Each of these companies came under competitive pressure from new technology. The cell phone has caused a huge drop in landline use. The paperless office has superseded photocopying. And cell phones have altered photography dramatically. 3 we did under competition. The difference between a monopolist and a firm under competition is that the former firm exploits its market power, while the later has none to begin with. 10.2 Reasons for the Existence of Monopoly 10.2.1 Control of a key resource Occasionally, a company is able to completely dominate control over an important resource necessary for the production of a product. Such a company will then have a monopoly in that product. Either the company actually owns the resource itself, or it owns much of the resource and controls the rest in some way, say, by legal contracts. Example: The International Nickel Co. of Canada owns most of the world's supply of nickel. Example: At one time ALCOA owned or controlled most of the world's supply of bauxite. In 1945 the Supreme Court forced them to sell off most of their holdings. In addition, the government sold its aluminum processing factories to two new upstart companies, Reynolds Metals and Kaiser Aluminum. This ended ALCOA's monopoly in the aluminum market. Example: The Metropolitan Opera Company signed most of the best opera singers in the world to exclusive, long term contracts giving them a monopoly over live opera performances. 10.2.2 Natural monopoly There might be what is called a "natural monopoly." This is where the technology yields increasing returns to scale. The cost structure will involve the LRAC and LRMC curves sloping downward through much of the range of output as in the diagram below. At the market price of p*, the firm will maximize profits under competition by choosing y*. This is the best the firm can do. However, at y* price p* is below average cost so the firm is earning negative economic profits. And it doesn't matter if the price rises because the same thing will be true at the higher price; the firm will attempt to maximize profit and in trying to do so will find that its economic profits are negative. Since this is the long run cost structure, the firm will go out of business as a result. Competition cannot exist with this type of cost structure, only some form of imperfect competition will. cost LRAC LRMC p* y* y Example: Some analysts now believe (2015) the airline industry is characterized by increasing returns over a broad range of output levels. This will make it impossible to induce true competition into the industry. 10.2.3 Legal barriers to entry Patents and copyrights create a monopoly for the inventor of an idea. This allows them to exploit their own idea and protects them from infringement. There is some tension here. We want people to come up with new, innovative ideas, and develop new products. However, once someone does, they become a monopolist. The tradeoff is between obtaining the benefits from new ideas against the cost of the subsequent monopoly. This leads to the study of the optimal length of a patent: for how long should we allow someone exclusive rights to the fruits of their own idea, 4 knowing that this will grant the person a monopoly that will allow them to exploit the market so created? Example: ALCOA invented a unique process for turning alumina into aluminum ingots by extracting oxygen from bauxite in the late 1880s and invented another process in 1903. Example: Polaroid "Instant-picture" cameras and film. Other Examples: Cash registers, cellophane, scotch tape, rayon, and intermittent windshield wipers. Example: The company that produces the board game "Monopoly," Parker Brothers, now owned by Habro, has a monopoly on the production and distribution of the board game "Monopoly." The downside is that an inventor requires protection from competition for a while. If anyone could steal your idea and produce a product that competes with you, you would have no incentive to develop your own idea. Property rights have to be protected as long as you want to provide people with an incentive to come forth with new ideas and new products.6 10.2.4 Exclusive franchise is granted by the government. The government grants one company the right to sell a product and prohibits anyone else from competing. Only that one company is allowed to produce, market, and sell the good. Example: US Postal service. Example: AT&T long distance phone service until the early 1980s. Example: Cable television company. Example: NASA and space exploration. One justification for granting such a license is to obtain the extra profits for the government. It was quite common in the age of exploration of the 15th and 16th centuries to grant a unique position to one trading company and then share in the profits. The British East India Company is a good example of this. The company was a joint stock company granted a royal charter by Queen Elizabeth in 1600 to trade in the Far East Indies. They mainly traded with India and much later China. Eventually the profits were so large that they attracted competition from another company. They mainly traded in luxury goods like silk, tea, and opium. The Company also dominated India politically.7 Another justification is to have the company gain profits in one activity in order to subsidize another activity. This might be appropriate from a social standpoint. One example is when AT&T charged higher rates for long distance telephone service in order to subsidize service in rural areas. This subsidy across activities hurt the company when it was forced to compete with MCI and Sprint in providing long distance service. Another example is the postal service. In many countries customers are charged a higher price for one service, e.g., first class mail, in order to provide mail delivery service for rural areas. 10.3 Product Differentiation The single aspect that differentiates a market where the individual firms have some market power from another market where the market participants do not is product differentiation. The firm must convince the consumer that its product has certain characteristics that the product of other firms does not. For example, one dishwasher-soap may have a lemon scent. Another 6 Under current American law the owner of the copyright has to sue someone who infringes on a patent or copyright. The police do not just go out and arrest a company that infringes on a patent. The reality is that large corporations can typically infringe on a patent until the inventor sues them. But a large corporation has lawyers on retainer and can usually beat an individual inventor since the individual has limited resources. 7 https://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/History/British/EAco.html 5 company might put out a similar product that is pink in color. A third company might produce a product that kills germs, and so on. There are two important implications of product differentiation: the firm's demand curve will slope downward, and advertising becomes more pervasive and the tone of the advertising changes; it no longer simply provides the consumer with information about the price and availability of the product but attempts to persuade the consumer. First, consider the case of competition. Price is determined in the marketplace. The firm believes that it can sell all it wants at the going market price. In that case, it believes that it faces a perfectly horizontal or elastic demand for its product, even if the market demand curve slopes downward. In the diagram below, the market price is p*, the market demand curve is D and the firm's belief about its demand curve is that it is perfectly elastic at p*, depicted as d. The firm can choose to be anywhere it wants to on its own demand curve. If the firm lowers its price it will lose money. If it raises its price, it will lose all of its customers and lose money. This is the classic case of a firm that has no control over its market at all. It literally takes price, technology, wage costs, taxes, and so on, as beyond its control. In producing and selling its product it is providing the good at the lowest possible price and the highest level of quality. If it cannot do this, then it will go out of business. This is what is in the back of someone's mind when you hear them extol the virtues of the market place, competition, and deregulation. Perfect Competition p Market S p p* p* Firm d D Q y Now consider a firm that believes it faces a downward sloping demand curve. The firm no longer takes price as given to it by the market. It can influence its own price through its choice of output. If it produces more, its price will fall, if it produces less, its price will rise. So the price it charges depends on its production y, p(y), where∆𝑝/∆𝑦 < 0, reflecting a downward sloping demand curve. The firm’s revenue is given by revenue = p . y, or revenue = p(y) . y. The change in revenue is, ∆𝑅 = (∆𝑝/∆𝑦)(𝛥𝑦)𝑦 + 𝑝𝛥𝑦, or !! ∆! 𝑀𝑅 = !! = ∆! 𝑦 + 𝑝. This is the marginal revenue of the firm. It is the extra revenue it gets when it produces one more unit of the good. What happens if it sells one more unit? It gets the price p. However, one more unit changes its price a little because demand is downward sloping. It changes it by (∆𝑝/∆𝑦) and this affects the other units it sells. So (∆𝑝/∆𝑦)𝑦 is the change in revenue when its price changes. Let MR represent marginal revenue where MR = 𝛥𝑅/𝛥𝑦. So 𝛥𝑝 𝑀𝑅 = 𝑝 + 𝑦 𝛥𝑦 Since the second term is negative, i.e., 𝛥𝑝/𝛥𝑦 < 0, marginal revenue is always smaller than price, MR < p. This is depicted below. The marginal revenue line will be a "line" if demand is linear. The marginal revenue “curve,” or line, will always be below the demand curve as long as the demand curve is downward sloping. 6 p, MR d y MR This is what we would expect from a firm with market power. When it raises its price it will not lose all of its customers, only some. When it lowers its price, it will not capture all of its competitor's customers because they may have brand loyalty to the competitor's product. Brand loyalty creates a downward sloping demand and a small amount of "monopoly" power for a firm. It can raise its price without losing all of its customers. For example, if you like Nike shoes better than other shoes, a small increase in the price of Nikes may not cause you to buy a different brand. With a higher price, you might simply wait an extra month to get your next pair of Nikes. A firm facing a downward sloping demand curve will also confront what is known as a marginal revenue curve in addition. Thus, the firm with market power confronts a demand structure and a cost structure. A monopolist is the extreme case where there is only one firm and hence a maximum of brand loyalty since there is no other brand. Example: linear demand. Suppose the firm’s demand is given by: p = 100 - 2x. The slope is Δp/Δx = - 2. This is graphed below as d, where x = y. It also follows that R = py = (100 - 2y)y = 100y - 2y2. Finally, marginal revenue can be derived in the following way, ΔR = 100Δy - 2(Δy)y - 2y(Δy) = 100Δy – (4Δy)y, So, MR = ΔR/Δy = 100 - 4y, which gives us the following graph, p, MR 100 d 25 50 y MR 10.4 Monopoly pricing A firm with market power will use the general rule that we derived earlier to maximize profit: choose output where MR = MC.8 Under perfect competition, MR = p so the profit maximization rule under competition is to choose y where p = MC. However, for a firm with market power, the rule is to choose y where MR = MC to maximize profit. In the diagram, first find the intersection point between MR and MC at point A. This yields y*, the profit maximizing level of output. Second, at y* go up vertically to the demand curve at point B and across to get 8 Profit = revenue – cost, or profit = R(y) – C(y), where revenue = R = p(y)y. The change in profit per change in output equals, 𝛥𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡/𝛥𝑦 = 𝛥𝑅/𝛥𝑦 − 𝛥𝐶/𝛥𝑦 = MR – MC. To maximize, set this to zero, MR – MC = 0, or MR = MC. The rule is: Choose output where MR = MC to maximize profit. 7 the price p*. This is different for a firm with market power. If this firm charges a price of p* consumers will buy y* and this will maximize the firm's profit because MR = MC at that point. p, MR, cost MC p* •B •A d y y* MR Next, we need to check whether the firm is earning an economic profit or not. We do this in the same way as under competition, compare p* with AC at y*. (The AC is not depicted.) If p* > AC, the firm is earning an economic profit and this will possibly attract entry into the industry, as in Chapter 9. If p* < AC, economic profit is negative and the firm is earning a lower than normal accounting profit. It must then face the shutdown decision in exactly the same way as the firm under competition. Shutdown if p* < AVC, produce if p* ≥ AVC. Finally, if p* = AC, it is earning a zero economic profit which is to say it is earning a normal rate of return on its capital investment. In that case it would be indifferent as to whether it should produce or shut down. All of this is the same as for the firm under competition. The only difference is that y* is where MR = MC and p* comes from the firm's demand curve, not the market demand curve. Monopoly is the special case where a single firm faces the entire market demand, D. So in the diagram above replace d with D and you will end up with the same result basically. The monopolist chooses ym, the monopoly output, where MR = MC (point A). Second, find the monopoly price pm for ym from the monopolist's demand curve (point B). Finally, we need to check to see if an economic profit is being made; compare AC with pm. If economic profit is positive, this will eventually induce entry into this industry and competition will occur. What is the monopolist's supply curve? Under competition we know that the firm's supply curve in the short run is the SRMC above the SRAVC from Chapter 9. In the long run the competitive firm's supply curve depends on returns to scale and on whether its unit costs like the wage rate are constant. If the competitive firm has constant returns to scale and constant costs, then its long run supply curve will be a perfectly elastic horizontal LRMC = LRAC touching the minimum point of the short run average cost curve. However, for a monopolist, there is no supply “curve” per se. There is only a supply “point.” The monopolist chooses one point and that yields a price and a quantity such that if that price is charged, then consumers will buy that particular quantity. In the figure above, the supply point would be given by y* and the monopolist would charge p* per unit from the demand curve. Remember, the demand curve always tells us how much people are willing to buy at the going price. So people are willing to pay p* in order to purchase a total quantity of y*. 10.5 Myths About Monopoly 10.5.1 “Monopolists can charge any price they want.” This isn't quite true. There is really only one price the monopolist will charge, the profit maximizing price. 8 10.5.2 “Monopolists earn exorbitant profits.” Again, this isn't always true. It is actually possible for a monopolist to lose money and even go out of business. In the diagram below, the monopolist is actually earning a negative economic profit. Why? Its profit maximizing point is at A, where MR = MC, the price it charges is B on its demand curve and its average cost at this output level is at point C. Since C is above point B at the monopoly output ym, its price is below its average cost, pm < AC at ym. Therefore, its economic profit is negative in this example. p, MR, cost MC AC p m C • •B AC •A d y ym MR Furthermore, if a monopolist is earning large economic profits this will eventually attract entry by new competitors into the industry. Competition will eventually lower price, increase quality and service, and induce innovation. However, many people with patents never produce a product and bring it to market and many that do, go bankrupt. So just having an idea and a patent is not a guarantee of earning large profits. 10.5.3 “Monopolists take advantage of the market with poor customer service and produce shoddy quality.” This may sometimes be true. For example, many people complain about their cable television service. Most markets are served by only one cable company. Prices tend to be higher and service lower in such markets as opposed to cable markets where there is a second provider. However, sometimes it isn't true. Anyone who comes up with a new idea can get a patent, develop a new product, and become a monopolist for a while. This is where many new products come from. A company that has a patent for a new drug is a monopolist. The tradeoff seems to be between monopoly exploitation and getting new products to market. If someone patents an idea and brings a new product to market, that individual becomes a monopolist in that product. What do you think would happen if we didn't allow people with new ideas patent protection? 10.5.4 “Monopolists can pass along all cost increases.” One implication of this is that if there is a certain increase in cost because of environmental regulations or taxation, the monopolist will simply raise its price by the amount of the increase in cost passing along to consumers the cost increase. This is not completely accurate as long as demand slopes downward. Recall that the marginal revenue curve is everywhere below the demand curve and it has a steeper slope. So an increase in cost will lead to an increase in price. However, the increase in price will be less than the increase in cost. Output will fall and price will rise when cost goes up but not by the full amount of the increased cost. This means that both consumers and the monopolist will share the burden of the increase in cost. 9 p, MR, MC a’’’ a’’ p, MR, MC b’’’ a’’’ b’’ a a’ MC a’’ b a b’ MC’ a’ D D MR MC Y1 Y0 MR Notice that economic profit is the gap between price and cost at the margin evaluated at the profit maximizing output level. Before the increase in cost this profit is given by area aa'a''a''', where a is the price choice given by the monopolist's output level Y0. Suppose cost increases from a'' to b'' because of some new environmental regulation. Price increases from a''' to b'''. Notice that this is less than the increase in cost. After the increase in cost, price rises to b as output falls to Y1. The profit is given by area bb'b''b'''. Profit falls as cost increases. The monopolist is unable to pass along the entire cost increase. Again, this is because demand slopes downward. The monopolist will be able to pass on more of the cost increase the steeper the demand curve is because a steeper demand curve leads to a steeper marginal revenue curve. If demand were perfectly inelastic, then and only then, could the monopolist pass on the entire increase in cost. In that case D = MR. 10.6 Application: Defense Contractors Large defense contractors bid for a job offered by the Defense Department. Once a particular company wins the bid and receives the contract, it becomes a monopolist in the sense that there is only one company that will produce a certain weapons system, for example, the Apache helicopter or the stealth bomber. Over time a particular firm may win a string of contracts from the defense department and develop some important expertise, e.g., building parts for the space shuttle, that helps it win future contracts. For example, Boeing supplied aircraft during World War Two and developed expertise that helped it win defense contracts after the war that actually helped it stay in business during the 1950s while it was developing the 707, one of the most popular planes ever built. In 2005 Boeing and Airbus became embroiled in a trade controversy that had been brewing for a while. Airbus received huge government subsidies from several European countries to cover their development costs. They are introducing the world's largest jumbo jet. Boeing claimed that the massive government subsidies are unfair. Airbus countered by arguing that Boeing benefited from lucrative defense contracts and without those contracts, Boeing would not be able to compete. In addition, Airbus wanted to compete for those contracts. A counterargument to this would be that these are US defense contracts and that foreigners should not have access to sensitive material that could compromise the national security of the US. As another example, consider the Hughes Aircraft Co. originally run by the billionaire Howard Hughes. The company developed a system for positioning satellites in the upper atmosphere. Having more than one system would create logistical and tracking problems and so the Hughes Company essentially became a monopolist. The US government used the system in 10 over 100 satellites in a breach of contract. The government filed a lawsuit against the Hughes Co. and argued that the Hughes Co. was behaving like a monopolist. The Court ruled in favor of the Hughes Co. who immediately countersued for $3.3b. The case was settled out of court. 10.7 Another problem with Monopoly? A firm may take actions that make it seem like it is acting in the best interest of the consumer now, e.g., charging a remarkably low price, however, once the firm has driven out the competition, it may become a monopolist or "near" monopolist. Microsoft attempted to do this by embedding Internet Explorer into its operation system when it was trying to drive Netscape out of the Browser business. Once that happens the firm will gradually allow its prices to drift upwards as it begins to take advantage of its monopoly position. Application: Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart hit on a brilliant idea for expanding its operations over twenty-five years ago. It began opening large stores in rural and suburban locations mainly concentrating on small towns and suburbs. It would open a store and drive out any small retailers who might compete with them. Since the town was small to begin with, the local market could not support another large box retailer like K-Mart, Sears, or Target. Wal-Mart dramatically increased in size during the 1980s and 1990s and eventually became the largest retailer in the world. By 2000 it was large enough to go "head-to-head" against other retailers like Sears in larger towns and cities. It would also appear to be the case that other retailers like K-Mart, Target, Shopko, and Sears are following Wal-Mart's lead by expanding their operations into rural areas and small towns since about 2005. This continued after the recession was over in 2009. Of course, the reason for doing this is to become a monopolist and exploit the local market as much as possible. Occasionally, a market is large enough to support more than one big box store, of course. In Lewiston, Idaho, for example, there is a JC Penny's, Sears, Wal-Mart, Shopko, and a Costco, although Sears and Penny's have gone a bit "upscale" with their product lines and so may not directly compete with Wal-Mart. They have co-existed in the local market for quite some time so this might be an equilibrium close to perfect competition since they are selling goods that are very similar, e.g., jeans, Coke, and bug spray. Application: We began deregulating the air travel industry in the late 1970s trying to induce competition. After almost thirty years of deregulation, prices for air travel are probably lower than they otherwise would have been in comparing the average fare in 2015 with that of 1990. However, when one has to pay a fuel surcharge, a charge for checked luggage, buy other items that used to be free like a can of soda and a snack, bring your own pillow, and endure long waits and poor "on time" arrivals, one really has to wonder about "quality" under competitive pressures. So fares, including all the extra fees, charges, and inconvenience of cramped seats and multiple layovers per trip, may be about the same or even more than thirty years ago. 10.8 Price Discrimination A monopolist can do even better in the sense of generating more profit than the analysis above would indicate if she can practice price discrimination among her customers. Basically, price discrimination involves either charging different customers a different price by segmenting the market, or charging a different price for different units sold. Typically, a monopolist who can do this will reap additional profits. The extreme case of price discrimination is where the monopolist can charge a different price for each unit sold. This is known as "perfect price discrimination" or first-degree price discrimination. Notice that in the diagram below, the classic monopolist studied so far in this chapter would charge p* and sell y* units. The monopolist's revenue is p*y*. Geometrically, this 11 is the area 0p*By*. Total cost is area 0CAy*. Profit is the difference between the two, rectangle Cp*BA, which is emphasized in the diagram. The consumer's surplus is triangle p*DB. Notice that there is some unexploited profit for the monopolist to go after, namely, triangle ABE. This is extra profit because it is above MC = AC. If the monopolist can practice perfect price discriminate, not only will she capture the entire consumer's surplus triangle, triangle p*DB, but she will also capture the triangle ABE as pure profit, thus increasing her profit from area Cp*BA to the full triangle, CDE. So her profit increases by areas p*DB and ABE if she can practice perfect price discrimination. p, MR, cost D p* •B C • E A • MC d 0 y y* MR How does perfect price discrimination work? Recall that the demand curve tells us exactly how much a consumer is willing to pay for each unit of the good. If the monopolist knows the demand curve and is able to charge a different price for each unit of the good, she can take advantage of the consumer's willingness to pay for the good. Consider the example depicted below. The consumer is willing to pay $10 for the very first unit. Under perfect price discrimination, the monopolist charges him $10 for the first unit. The consumer is willing to pay $9 for the second unit purchased. If the monopolist knows this, she can charge the consumer $9 for the second unit, and so on for the third (p=$8), fourth (p=$7), and fifth (p=$6) units, charging a different price for each subsequent unit. If the monopolist can practice perfect price discrimination, the monopolist can extract all of the consumer's surplus triangle from consumers. Under the classic case of a monopolist, some of the consumer's surplus accrues to the consumer, namely, area p*DB above. However, none of it accrues to the consumer under perfect price discrimination. It is all captured by the monopolist. Furthermore, the price charged for the very last unit will be pd. This is an unusual result. Under competition, price = MC would result in total industry-wide output being equal to yd and price = pd in the diagram. Yet, this is exactly the same result under perfect price discrimination. So apparently, output will be the same under perfect price discrimination by a monopolist as it is under competition. The difference is that under competition everyone pays the same price for any unit they buy, pd, and it is consumers who reap all of the consumer's surplus as a result. Under perfect price discrimination, a different price is charged for each unit and it is the monopolist who receives all of the consumer's surplus, not the consumers. 12 p, MR, cost 10 !9 8 Consumer's Surplus Triangle MC pd d y 1 2 3 yd How would we actually calculate the consumer's surplus area? The area of a triangle is half the base times the height. The base of the triangle above is the distance yd - 0. The height of the triangle is the distance $11 - pd. So the area of the triangle is (1/2) x (yd - 0) x (11 - pd). If we knew pd and yd we could crank out the actual number representing the consumer's surplus in this example. In this case, this is the extra value that goes to the perfect price discriminating monopolist that would otherwise accrue to consumers under perfect competition, holding everything else constant. Perfect price discrimination is somewhat unrealistic. However, there are imperfect forms of price discrimination that are a bit more realistic. For example, sometimes a monopolist is able to charge consumers one price for one block of units and charge a second price for another block of units. This is known as second-degree price discrimination. Public utilities like power companies routinely engage in this sort of price discrimination. For example, you might be charged one price for a given level of power usage and a second price for incremental usage. Avista began using such a scheme in 2014. The price differential must be unrelated to cost differences. If you are charged a higher price for electricity during the month of August relative to the month of May and this is due to the higher cost of power during peak periods of use, as occurs when everyone is using air conditioning, this is known as "peak load pricing" and is due to cost differences. Price discrimination involves differential pricing on the basis of knowing detailed information about the demand curve that is unrelated to the costs of generating the output. Example: Telephone companies charge different long distance rates for calls that last more than twenty minutes. The caller pays one price for the first twenty minutes and then pays a lower price after that. This is second-degree price discrimination since the caller is being charged a different price for a different block of units bought. A third form of price discrimination, known as third-degree price discrimination, is where a company charges a different price in a different, but related, market. Sometimes a firm can segment its customers into two or more groups and can charge consumers in each group a different price. Example: Movie theaters charge seniors a lower ticket price than younger people. Example: Children pay a lower price to get into some amusement parks than adults. Example: Power companies often charge industrial customers a lower price than they charge residential consumers because the demand for power by industrial users is typically more elastic than residential demand. Example: Doctors charge patients who have insurance more than patients who do not for the same service. Example: Doctors charge poor patients less than wealthier patients for the same service. 13 Certain conditions have to hold before second and third degree price discrimination can be practiced. First, the firm must have some market power. If the firm has no market power, then it will not be able to exploit its market. Second, it must be impossible for the consumer to purchase the product and then resell it. This is important because if the consumer can resell the product, side markets will spring up and arbitrage will occur making it impossible for the monopolist to exploit its monopoly position. For example, suppose seniors have a more elastic demand for a new car than non-seniors. A price discriminating car dealer would charge a senior a lower price for a car than non-seniors. A senior could turn around and resell the car at a price more than what they paid but lower than the car dealer is charging other customers. If enough seniors did this, then the price would be driven down from what the dealer is charging non-seniors because nonseniors would buy only from seniors on the second hand market and not from the dealer. Contrast this with a doctor. It is impossible for a patient who pays a low price to the doctor for some service to resell "doctor services" to someone else. Third, the firm that can segment its market will only increase profit by charging different people a different price only if they have different elasticities of demand. If everyone has the same elasticity, then the firm will charge them the same price when it maximizes profit. To see this last point, suppose there are two types of buyer, and let y1 = sales to buyer of type #1, y2 = sales to buyer of type #2, p1 = price paid by buyer #1, p2 = price paid by buyer #2, R1 = revenue from market #1, R2 = revenue from the second market, and C(y1 + y2) is total cost of producing y1 + y2. The firm’s profit is π = R(y1) + R(y2) - C(y1 + y2) when the firm can segment its total market into two parts. The optimal choice for y1 satisfies, MR(y1) = MC, and the optimal choice for y2 satisfies, MR(y2) = MC. If MR(y1) = MC and MR(y2) = MC, then MR(y1) = MR(y2). What determines marginal revenue? The marginal revenue is given by,9 MR = p(1 - 1/ε). So if MR(y1) = p1(1 - 1/ε1) and MR(y2) = p2(1 - 1/ε2), and we know that MR(y1) = MR(y2), then we have the elasticity formula, 𝒑𝟏 𝟏 − 𝟏 𝟏 = 𝒑𝟐 (𝟏 − ) 𝝐𝟏 𝝐𝟐 If the elasticities are the same, then the price is the same and it doesn’t increase profit to price discriminate. On the other hand, if buyers of type #1 are more responsive to price than buyers #2, ε1 > ε2, then the firm can increase its profit by charging type #1 a lower price than type #2, i.e., p1 < p2. 9 From earlier in the course, MR = p + y(Δp/Δy), or MR = p(1 + (y/p)(Δp/Δy)). But, the elasticity of demand is given by ε = - (Δy/Δp)(p/y). Combining these two equations, we obtain MR = p(1 - 1/ε). This is what you need to know, not the way we derived it. 14 The intuition is the following. Suppose the firm is charging both types the same price. Can it increase its profit by charging a different price? If the demand curve is really flat so the elasticity is large, lowering the price increases sales a lot and increases revenue a lot. On the other hand, if demand is steep or inelastic so the elasticity is really small, then the firm can increase its profit by raising the price. So the firm can increase its profit by lowering the price to buyer #1 and raising the price to buyer #2. Example: Suppose the elasticities are the same. If ε1 = 1.32, ε2 = 1.32, then p1 = p2. To show this, substitute into the elasticity formula. Example: Movie ticket pricing. Suppose there are seniors (buyer #1) and non-seniors (buyer #2) who go to movies. Let p1 = 1, ε1 = 3, and ε2 = 2. Then 1 – 1/ε1 = 2/3 and 1 – 1/ε2 = 1/2, so the formula p1(1 - 1/ε1) = p2(1 - 1/ε2) becomes 2/3 = 1/2 p2 so p2 = $1.33, and p1 < p2. A third degree price discriminating monopolist should charge seniors a lower ticket price than nonseniors, and by doing so will obtain additional profit than if seniors paid the same price as everyone else. Why is this true? This is true because seniors will go to a lot more movies at the lower price since their demand is more elastic than non-seniors. Example: Scalping M’s tickets. Suppose there are two types of buyer who want M’s tickets, buyer #1 has demand with an elasticity of ε1 = 1.42 and buyer #2 has demand with an elasticity of ε2 = 2.267, so buyer #2 has a more elastic demand. Suppose the current price being charged for buyer #2 is p2 = $32.50. Substitute, 1 – 1/ε1 = 0.295 and 1 – 1/ε2 = 0.5588, so the formula p1(1 - 1/ε1) = p2(1 - 1/ε2) becomes p1(0.295) = 32.5(0.5588), or p1 = 61.41. Since demand by buyer #1 is less elastic than buyer #2 (2.267 > 1.42), the monopolist will charge buyer #1 a higher price than buyer #2 to maximize profit. This will work as long as buyer #1 cannot buy a ticket from buyer #2. What do you think will happen to the price of an M’s ticket if buyer #1 can buy tickets from buyer #2? This is why “scalping” of tickets is illegal. It protects the M’s monopoly right to price discriminate against rabid fans who have a low elasticity demand for M’s games! 10.9 Applications 10.9.1 International Price Discrimination An application of price discrimination involves charging customers in one country a different price than customers in another country. “Dumping” is when a company in one country sells its products below cost in another country in order to invade its market and take it over as a monopolist. As soon as the company drives out the local competition, it raises its price and exploits its monopoly advantage. It can be very difficult to prove dumping. One must know the “true” cost of production and there is enough variation in an industry across countries because of culture and other local institutions, e.g., labor market laws, fair wage laws, to make it difficult to calculate cost. The country bringing the accusation must have cost data from a company in another country and obtaining this information can be problematic. The Fuji Photo Film Company of Japan had a virtual monopoly on the sale of paper and chemicals for photo processing in Japan. They entered the US market in the 1980s and began selling Fuji film well below cost using their monopoly profits in Japan to finance the below cost sales in America. By the early 1990s they had captured about 17% of the US market, mostly at the expense of Eastman Kodak. Kodak charged that this constituted "illegal dumping.” In 1993 the US Department of Commerce charged Fuji with "dumping." In 1994, Fuji signed an agreement under which it would sell at the "fair market price" as determined by the US Department of Commerce for five years. Fuji began building a production facility in the US. 15 Kodak then charged that Fuji was keeping Kodak out of the Japanese market! Fuji responded by arguing that Kodak was acting like a monopolist in trying to dominate the market.10 Other recent notable examples include silk, solar panels, and steel. In 2006 India accused China of dumping silk on the market. China is the largest producer of silk and India is the largest market for silk. The low price charged by Chinese companies caused some Indian silk manufacturers to lobby their government for protection. India retaliated by imposing tariffs on silk imported from China.11 US solar panel manufacturers accused Chinese companies of dumping solar panels in the US market in 2011 to drive them out of the market.12 And in 2014 the US imposed punitive tariffs on imported steel from nine countries including notably South Korea. A tariff of 118% was imposed on imported steel, although much lower tariffs were imposed on the two main steel producers exporting steel from South Korea to the US.13 10.9.2 College tuition. Should colleges charge students different tuition for different majors? Once a student enrolls in college and starts taking classes, the college or university becomes a monopolist for that student. The student can transfer if they don't like it, however, most don't, especially after they get past their freshman year and into a major. The analysis of price discrimination strongly suggests that universities should employ price discrimination in charging differential tuition across majors. This will increase their revenue and they can use this additional revenue to keep all tuition down (or spend it on the football team). Most universities charge graduate students and out-of-state undergraduates more in tuition. This is a form of price discrimination. Some colleges and universities charge students in pharmacy and veterinary medicine programs more. Other colleges are discussing plans to charge engineering students and business students more in tuition. Our analysis suggests that they need to charge higher tuition for degrees that are in inelastic demand and lower tuition for degrees in more elastic demand. 10.10 Other monopoly tactics: tying and bundling Monopolists use other tactics to extract consumer's surplus as well. Tying and bundling are two such examples. Tying is a situation where the consumer has to buy one product in order to consume another product and the firm charges a price for the second product above average cost. This is a form of price discrimination since the firm can charge a price above average cost for the tied commodity. This increases its profit. Example: Cable television companies force you to use their converter box to unscramble their signal when less expensive alternatives are available. The monthly converter box fee is set above their AC of providing the descrambler. Example: Franchise owners of McDonald's had to buy their supplies from McDonald's. McDonald's could then charge them a price above AC for hamburger, buns, oil, etc., and earn additional profit. Basically, tying is a form of price discrimination because the monopolist is able to target a segment of the market and exploit it by forcing customers to pay a special price for one of its products, namely, the product that is tied to the product initially purchased or leased. Bundling is a form of tying where the firm bundles several goods into a package and sells the package rather than the individual parts. 10 http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/stories/1993-09-12/is-fuji-dumping-or-competing http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/5224370.stm 12 http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/20/business/global/us-solar-manufacturers-to-ask-for-duties-on-imports.html?_r =0 13 http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-steel-dumping-20140711-story.html 11 16 Example: Cable television companies sell a package to you that includes channels you don't want. You have to buy the whole package in order to get the channels you do want. This is done so the monopolist can raise the price of the entire bundle thus forcing you to pay a positive price for channels that you would don’t want to buy. Examples: Microsoft Office, a “bundle” of songs in a CD, McDonald’s Happy Meal.14 10.11 A first look at Game Theory: Cartels Game Theory is a powerful tool that can be used in any situation involving strategic behavior. There are many situations in economics where it can be used to teach us something about the way people interact in markets. People instinctively use game theory type reasoning in a lot of situations without realizing it. For example, a pitcher in baseball has to choose what type of pitch to throw to the hitter, the hitter has to anticipate what type of pitch will be thrown and decide to swing or not, and the pitcher has to anticipate what the hitter will do. A football team, who has the ball on the goal line with seconds to go in a Championship game, must decide what type of play to call, the other team must anticipate that play and defend against it, and the first team must anticipate what kind of defense will be used. As a more serious example, during the Cold War countries formed alliances and would take actions in anticipation of how the other alliance would respond. The Soviets put missiles into Cuba in 1962 anticipating what the Kennedy Administration would do, and the Kennedy Administration responded by blockading Cuba anticipating what the Soviets would do next. Finally, Coca Cola and Pepsi introduce new products in anticipation of what the other company will do. In the early 1980s Coca Cola introduced the “New Coke” with higher sweetness content than regular Coke because it was losing market share to Pepsi. This turned out to be a disaster and Coca Cola had to reintroduce its old product under the guise of "Classic Coke."15 The key to understanding how the game will operate is to try to put yourself in the shoes of one of the players of the game. You have to form expectations of what the other player will do and this helps you put together a strategy for playing the game. The following is a typical "one shot" game because it is only played once. Consider the following game with two firms, called a duopoply, who have to choose output in anticipation of what the other firm will do. There are two firms A and B. There are two possible actions: produce a high output or produce a low output. The profits are listed in the table. In order to figure out what the equilibrium will be we have to decide on what each player in the game will expect the other player to do and then if both players play according to their expectations, then this is a potential equilibrium outcome. We then check that outcome to see if either player has an incentive to unilaterally deviate from her strategy, holding the other player's strategy constant. If neither player has an incentive to deviate from their proposed strategy, then that set of strategies (one for each player) will be a Nash equilibrium.16 14 http://www.forbes.com/sites/hbsworkingknowledge/2013/01/18/product-bundling-is-a-smart-strategy-but-theresa-catch/ 15 Scientists at Pepsi discovered how much sweetness was required to activate a consumer’s taste buds. Since Pespi is sweeter than Coke, it would take more Coke to activate the taste buds. In the Pepsi taste tests, consumers were given two paper cups with just enough liquid to activate the taste buds for Pepsi but not enough for Coke. Consumers overwhelmingly chose Pepsi over Coke. In Coke’s taste tests, designed in response to Pepsi’s, more liquid was given and the results were more evenly split. 16 This is named for the man who first discovered this concept, John Nash, depicted in the movie, “A Beautiful Mind,” with Russell Crowe playing Nash. John Nash won the Nobel prize for this research and the movie won four Oscars including Best Picture. 17 B A low output high output low output 5, 5!! 1, 7 high output 7, 1 2, 2 A can choose either low y or high y and similarly for B. A is choosing a row and B is choosing a column. Each player is trying to anticipate what the other player will do. There are four sets of payoffs listed in the table. The first number is always A’s payoff while the second number is B’s payoff. Players choose trying to make their payoff as large as possible. For example, if A chooses low output and B chooses high output, A gets a payoff of 1 and B gets 7. First, consider A’s choice of strategy. Suppose A thinks B will choose low y, the left column which is highlighted. If A chooses low y they get a payoff of 5. If A chooses high y, they get a payoff of 7. Obviously, they will choose the action that gets the 7, high y. Suppose A thinks B will choose high y, the right column. A will get a payoff of 1 if they choose low y and a payoff of 2 if they choose high y. Since 2 > 1, A should choose high y. Consider B’s choice. Suppose B thinks A will choose low y. Then B’s payoff is 5 for low y and 7 for high y. They will choose high y since 7 > 5. Suppose instead that B thinks A will choose high y, the second row. B will receive a payoff of 1 for low y and 2 for high y. B will choose high y to get 2. A and B both know the payoffs and that their opponent is playing the same way. We ask is (low y, low y) a Nash equilibrium? To answer the question we fix B’s choice and ask if A can do better by deviating from low y. The answer is YES, they can by choosing high y since 7 > 5. Therefore, if A thinks B will choose low y, A will choose high y. Therefore, the proposed equilibrium of (5, 5) is NOT a Nash equilibrium. The only Nash equilibrium is where both choose high y with payoffs (2, 2). If A thinks B will choose high y, A’s best choice is high y so they won’t deviate. If B thinks A will choose high y, B’s best choice is high y so they won’t deviate. So neither player can do better than high y when the other player chooses high y. 18 Notice that if the firms get together and form a cartel, they can do even better. If both decide to collude instead of compete, then they will both restrict their output. The "Cartel equilibrium" is (low output, low output) and the "equilibrium" payoffs are (5, 5). Both firms are better off if they can form a cartel; they earn higher profits from the cartel than they can on their own. What incentive does A have after secretly agreeing to form a cartel with B? As soon as the secret agreement is finalized, A should cheat on the cartel. Why? Because if B goes along with the cartel agreement and chooses low y, and A cheats, A's profit increases from 5 to 7. Unfortunately, for the cartel members, B has exactly the same incentive. So both will eventually cheat on the cartel. That is why cartels are inherently unstable. A cartel is not identical to a monopolist. Sometimes a cartel is labeled a "monopolist." It is quite popular, for example, to refer to OPEC as the "oil monopoly” instead of as the “oil cartel." However, this is not a good description of a cartel's behavior since almost all cartels suffer from instability from time to time. This instability is due to the fact that the individual member's incentives differ dramatically from the group's incentive taken as a whole. This is not true of a monopolist. Also notice that the structure of the interaction between the two players is very special. Essentially, it is individually rational for a player in this game to choose high output since they are better off as an individual. However, if both players do that, the outcome appears to be collectively irrational. This is an example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma structure of Chapter 1. 10.12 More examples of cartels Example: OPEC. This is the most famous example of a cartel. In the early 1970s the MC of a barrel of Saudi light crude, the highest quality crude oil, was about 50¢ and OPEC was charging about $1.5 on average. After the war with Israel in 1973, OPEC tried to embargo the United States and the Netherlands as punishment for helping Israel. The price of oil on world markets quadrupled in a six month period. This caused the recession of 1975. We also discovered just how important energy was to the functioning of the economy. OPEC boosted the price again in 1979-1980 creating sluggish growth and more inflation. At one point the price per barrel was well over $30. However, Nigeria began cheating on the cartel by pumping more oil than its allotted share and the Iran-Iraq war began in 1980 when Iraq attacked Iran trying to capture its oil fields. Both countries began pumping more oil than their allotted share and world oil prices tumbled. By the mid 1980s the price was below $15. The Persian Gulf War of 1991, the invasion of Iraq by US forces, and events in Iraq, Iran, Venezuela, and Nigeria caused a great deal of nervous trading on energy markets and the price of oil reached $70 per barrel in 2006, a record at the time. Price speculation in 2008 over events in the Middle East drove price over $140 per barrel causing gas prices in the US to spike at well over $4.00 per gallon nationwide. This prompted a shift toward energy efficient cars causing huge problems for the big three automakers who had relied on the SUV market.17 Example: The coffee cartel. The Kennedy Administration wanted to increase spending on foreign aid in order to help developing countries. This was primarily to ensure that such countries did not fall into the hands of communists. However, the Congress was very reluctant and did not pass the necessary legislation. To get around this the Kennedy Administration formed the coffee cartel. Most coffee is produced in less developed countries but consumed in wealthy, northern countries in North America and Europe. The coffee cartel would restrict its own output thus raising the price of a bushel of coffee. This would act as an implicit subsidy 17 http://www.loc.gov/rr/business/BERA/issue5/cartels.html 19 since more money would flow from the wealthy "north" to the poor "south." At one time the cartel contained over 115 member countries. Unfortunately, most coffee is fairly homogeneous and it is difficult to detect cheating on the cartel when there are so many members. By the late 1960s there was so much cheating on the cartel agreement that the cartel had effectively collapsed. Example: De Beers diamond cartel. Some regard this cartel as the most successful cartel ever. In the late 1870s diamonds were discovered in southern Africa. Cecil Rhodes, who made his first fortune in gold mining, formed the De Beers company in 1887.18 Essentially, the cartel controlled the sale and distribution of low grade industrial diamonds as well as high quality diamonds used to make jewelry. The Central Selling Organization (CSO) would hold auctions periodically, mostly in London. Diamond buyers would be invited to an auction and could bid on the diamonds. Only about 300 - 400 buyers worldwide are invited; it is a very small club. The rules for buying and selling the diamonds are very stringent and controlled by De Beers. Breaking the rules is unheard of because of the possible punishment De Beers would inflict. When new diamonds are discovered, the new company or country is asked to join the cartel. By the early 1960s the cartel controlled about 90% of the diamond market. The cartel has attempted to stabilize prices and has typically succeeded. For example, in 1992, a large quantity of diamonds was smuggled out of Angola, a war torn country experiencing a long and protracted civil war. The diamonds threatened to flood the market thus dropping prices dramatically. De Beers spent over $500 million to buy up the diamonds and hence maintain the price. Several countries have tried to cheat on the cartel. Zaire refused to join the cartel when low quality industrial grade diamonds were discovered in Zaire. The cartel threatened to dump industrial diamonds on the market to drive the price below the average cost of mining the diamonds in Zaire unless they joined the cartel. Zaire called the bluff and, unfortunately, for Zaire, De Beers did exactly what it said it would do; it drove the price below average cost. In addition, De Beers threatened potential buyers who might buy from Zaire instead of the cartel. The end result was that Zaire eventually joined the cartel. When diamonds were discovered in Australia, they joined the cartel right away, rather than suffer the fate of Zaire. However, the Soviet Union, now Russia, have been trouble for the cartel, selling diamonds below the cartel price to earn foreign exchange to buy western technology and machinery. In 1992, economic conditions worsened in Russia and it began a large scale sell-off of its gold, oil, and diamond deposits. De Beers started flooding the market with diamonds in an attempt to punish Russia. However, this proved difficult. The most serious threat has come from Lev Leviev, a Russian who was once a registered buyer from De Beers. Leviev did not like the high handed treatment he received from De Beers and decided to break the cartel. He went directly to diamond-producing governments and made deals with them giving them more of the profit than De Beers did. This broke De Beers' stranglehold on the diamond market, and has made him a billionaire and a local hero in Russia. More recently, Canada and Australia have broken away from the cartel and De Beers had to change its strategy, focusing more on marketing its own diamonds to customers. Its 80-year dominance of the diamond trade effectively ended when the Oppenheimer family sold its majority stake thus ending the most successful cartel.19 Other examples of cartels: In 2007 the European Commission imposed a large fine on 11 electrical power equipment supply companies for creating a cartel led by the German firm Siemans in the pricing of power equipment. They essentially carved up the European market amongst themselves from 1988 to 2004 and set prices to limit competition. 18 19 The country Rhodesia was named for Rhodes. So, too, is the Rhodes Scholar program, and the Rhodes candy bar. http://www.businessinsider.com/history-of-de-beers-2011-12?op=1p 20 A number of banks were caught manipulating the foreign exchange market in 2015. Four of the world’s largest banks pleaded guilty to manipulating the foreign exchange market. Five banks paid large fines. Barclays, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, UBS, and the Royal Bank of Scotland were fined over $5 billion. The way the scheme worked was simple. A trader at one bank would build up a large position in a particular currency and then sell all at once to move prices. Traders at other banks would go along with the price movement coordinating their efforts via chat rooms. The banks got away with it from 2007 to 2013 because this market is one of the most lightly regulated and traders took advantage of this. The Justice Department noticed that the largest airlines are cancelling flights with greater frequency and flying with planes near capacity earning record profits. They are now investigating the airlines to see if they are acting as a cartel to collude against consumers by limiting flights and reducing seats to keep fares high and profits high. Delta, Southwest, American, and United fly approximately 80% of all passengers in the US.20 10.13 The Break Up of AT&T AT&T used to be "the phone company." You rented a phone from them, used their local service, and made long distance calls over their network. Gradually, competitors were allowed in the long distance market and a number of companies began making phone equipment. The Justice Department argued that some of AT&T's practices were illegal because they were designed to eliminate competition in the long distance market and the telephone equipment market and in 1974 brought suit against AT&T. After eight years of legal battling, and after spending over $350 million to defend itself, AT&T agreed to divest itself of 22 local telephone companies (about 2/3 of its assets) and give up its monopoly on long distance service. In exchange, AT&T was allowed to keep Western Electric, its manufacturer of equipment, and Bell Laboratories, its research company. It was also allowed to enter the cable television market. MCI and Sprint, quickly entered the long distance market and captured about 30% of the market by 1995. Long distance rates fell about 39% between 1983 and 1991 as a result of competition but increased about 11% from 1992 to 1995. In addition, AT&T wants to move into Europe. Many phone companies in Europe are run by the government and charge twice what consumers in the US pay. 20 http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/doj-investigating-potential-airlinecollusion/2015/07/01/42d99102-201c-11e5-aeb9-a411a84c9d55_story.html 21 The cell phone has completely changed this market. The demand for landlines has been falling since the early 2000s, while the demand for cell phones has been increasing, according to the graphic from the CDC. The latter will probably outpace the former by 2015. In fact, the cell phone would probably have broken up AT&Ts monopoly eventually. This is another example of a company earning profits that attracted new competition based on a new technology. 10.14 Taxing monopolists One policy that might be pursued in the case of a monopolist would be to impose a tax on their sales. This would be an attempt to tax their profits. However, the monopolist might try to pass on the entire cost to consumers. Can they? The short answer is no. Initially in the left hand diagram the monopolist chooses Ym and charges price pm. Its economic profit is the emphasized rectangle. Suppose now the government imposes a tax on the monopolist. The revenue generated by the tax can then be used to subsidize low income consumers who must buy the product, e.g., electrical power, from the monopolist. We can model this as an increase in the marginal cost of the monopolist from MC to MC’. Can they pass along the entire tax? The answer is no. Marginal cost will rise. However, marginal revenue and demand are still the same. So price will rise, but not by the full amount of the tax increase, i.e., the distance between MC and MC’. So both consumers and the monopolist will share in the burden of the tax. More importantly, some of the monopolist’s economic profit has been reduced. Unfortunately, some of the consumer’s surplus is lost, too. 10.16 Conclusion and a caveat Two remarks are in order. First, a monopolist will exploit the market as much as possible. This creates a welfare loss since the monopolist is restricting output in order to keep the price high. Consumers are worse off as a result. However, some monopolists bring new products to the market that consumers want. So there is tension between a monopolist exploiting the market and the new products they provide. Second, if it is true that monopolists earn extra normal profits, these profits will attract new entrants who want to compete for the extra profits. Eventually, the monopolist will face competition. It is rare when they do not. Power companies are one exception where the monopolist may not face much competition. One might also point to cable companies. However, many consumers find alternatives that effectively compete with cable companies like Dish TV and watching television shows and movies on the internet. 22 Important Concepts Reasons for monopoly Key resource Natural Monopoly Legal barriers to entry Exclusive franchise Product differentiation Monopoly pricing Problems with monopoly Price discrimination Tying Bundling Cartels Review Questions 1. What is the definition of a monopolist? 2. List some of the reasons for the existence of a monopoly. 3. Why is product differentiation important? 4. How does a monopolist go about choosing her price and output? How does this differ from a firm operating under perfect competition? 5. List some of the adverse consequences of monopoly. 6. What is price discrimination? 7. What are the different forms of price discrimination? Explain each. 8. Many firms price discriminate. Why? 9. Discuss what tying and bundling are. 10. What is a cartel? How does a cartel differ from a monopolist? 11. What are the different forms of price discrimination? Explain each. 12. How does a monopolist respond to a tax imposed on it? Can it pass on the entire tax to consumers in higher prices? Practice Questions 1. A monopolist cannot exist without some barrier to entry. a. True. b. False. 2. Which statement is true? a. Consumer surplus is greater under monopoly than under competition. b. Monopolists can literally charge any price they want to. c. Monopolists are able to restrict output to keep the price high. d. Monopolists earn exorbitant profits. 3. ALCOA was a a. cartel of aluminum producers. b. monopolist. c. perfect competitor. d. natural monopolist. 23 4. Perfect price discrimination is a situation a. where some consumers are charged a higher price than others. b. that is illegal. c. one good's purchase is tied to another by price. d. where each consumer pays a different price for each unit of the good. 5. The main difference between a cartel and a monopolist is that a cartel is inherently unstable. a. True. b. False. 6. Suppose a firm can segment its market into three pieces. What is the firm’s revenue and cost? 7. Suppose the firm of the last question wants to impose different prices to increase its profit. Assume 𝜖! = 1.17, 𝜖! = 1.17, and 𝜖! = 2.05. Let 𝑝 = 1. What prices should it charge buyers #2 and #3? 24 Answers 1. a. 2. c. 3. b. 4. d. 5. a. 6. 𝑅 = 𝑝! 𝑦! + 𝑝! 𝑦! + 𝑝! (𝑦! ) and 𝐶(𝑦! + 𝑦! + 𝑦! ). 7. p1 = 1 and 𝜖! = 1.17 = 𝜖! so p2 = 1, and p2 is obtained from the elasticity formula, ! ! 𝑝! 1 − ! = 𝑝! (1 − ! ), 1(1-1/1.17) = p3 (1-1/2.05) so p3 = 0.28, after rounding down. ! !