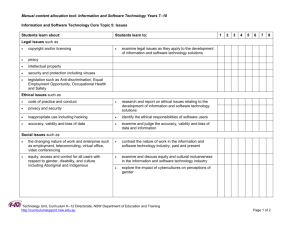

History - Curriculum Support

advertisement