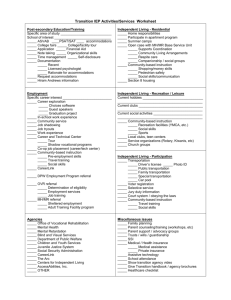

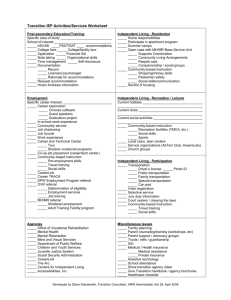

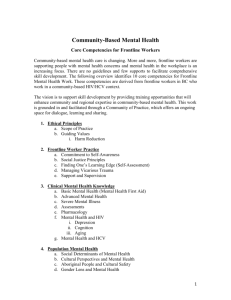

Community-based approaches and service delivery

advertisement