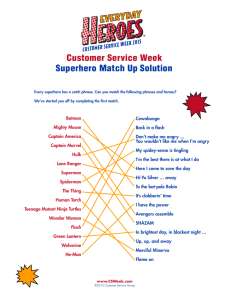

The Captain America Conundrum: Issues of

advertisement