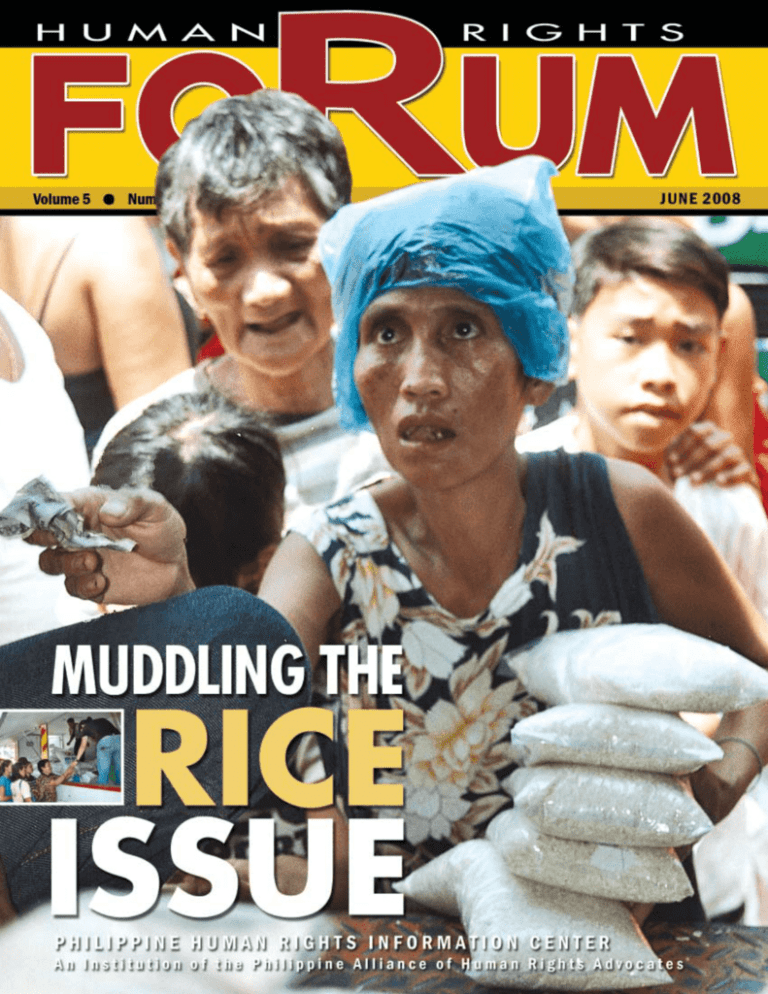

Human Rights Forum June 2008 - Philippine Human Rights

advertisement