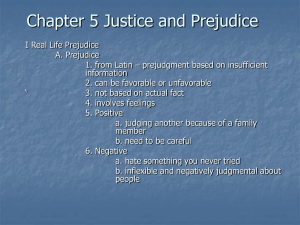

Controlling Prejudice and Stereotyping

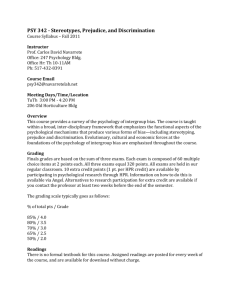

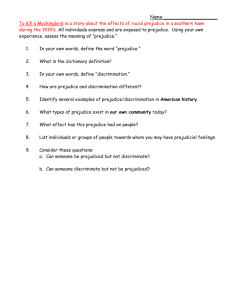

advertisement