C10 J-255

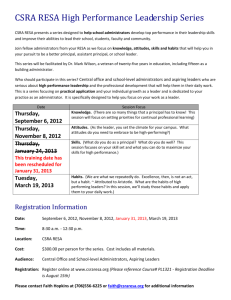

advertisement