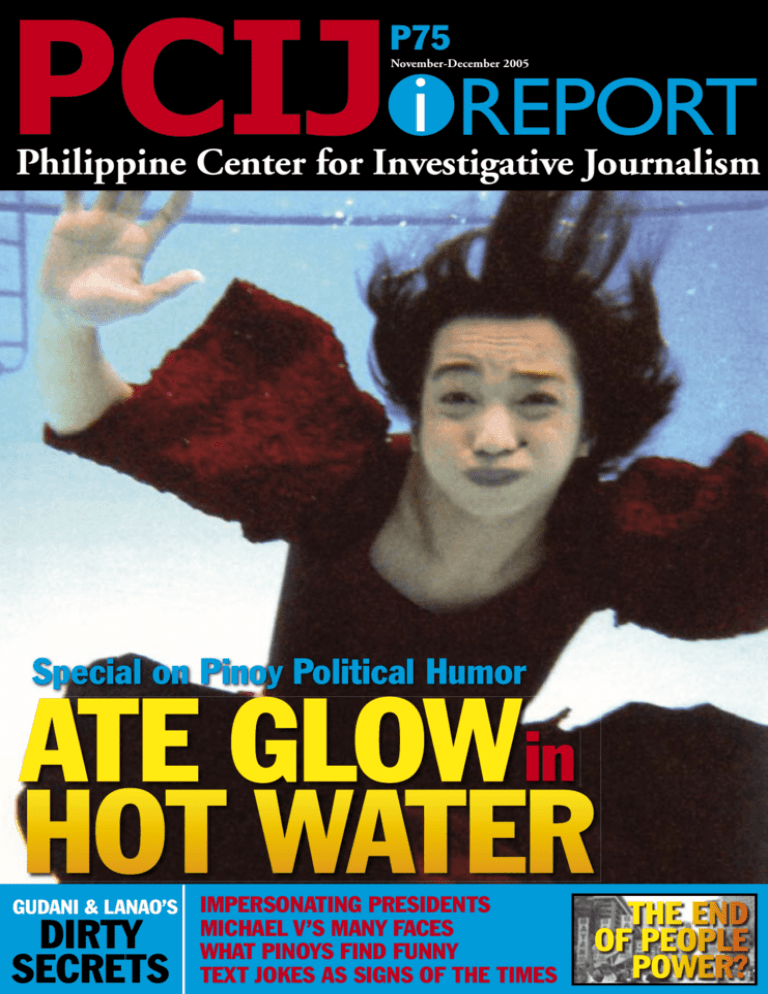

01 political satire cover.indd - Philippine Center for Investigative

advertisement