pdf here - relationalthought.com

advertisement

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF THINGS

FROM ORGANIZING SUPERSTRUCTURE TO ARTICULATION OF DESIRE

(Robert A. Gorny)

In the following text I want to re-strategize the notion of ’infrastructure’,

which recently gains importance within architectural discourse of our

globalizing world, in regard to the processes of modernization over the last

200 years. To better understand todays emerging space of our network age,

it might be necessary to look deeper in the processes at the beginning of the

machine age — and moreover the longstanding genealogy of critical positions

towards it, and the epistemic counter-models transcending the mechanical

views that have launched the technocratic and disciplinary processes over

modernity — that have shaped the world we inhabit today.

Shed in this light, what does the notion of infrastructure bring into the

discussion? When all paradigms are altering from objects themselves to

their connection and underlying relations, the development towards

relational perspectives should be understood in the ongoing reformulation of

the architectural discipline, from an object-centered discipline, into a systemstheoretical1 practice and knowledge of built environment. Today where

infrastructures and networks become a new dominant cultural logic of our

world, we witness a replacement of what Foucault coined as the biopolitical

paradigm of modernity, which partly causes the mediological crisis we see

in architecture today, to define a new role.

More than being only a material network, infrastructure primarily

prepares the subgrade (that is, the ground upon which the foundation of a

structure is built) for the exchange of everyday goods and affects, work and

services. In order to understand the implications of recent transitions regarding

the production of built environment, and to conceive tools for a new leitmotif,

architectural discourse is in need for, what we can call, a new materialism of

relations.

My aim in the following is to use Charles Fourier's theory of 'passionate

attraction' in order to introduce a specific libidinal aspect in the contemporary

discussion of infrastructure. By starting to reread infrastructure (including soft

once as institutions) as a collective articulation of desire to produce and enact

relationships, I will show how it manifests a late counterpart to the modern

paradigms of ordering, separation and segmentation, that has eventually

preconditioned the operational reversal of todays globalizing network society.

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

1 DESIRE MATTERS

In Fourier’s system of Harmony all creative activity including industry, craft, agriculture,

etc. will arise from liberated passion — this is the famous theory of 'attractive labor.'

Fourier sexualizes work itself — the life of the Phalanstery is a continual orgy of intense

feeling, intellection, & activity, a society of lovers & wild enthusiasts. (Bey 1991, 4)

As Lars Bang Larsen made it explicit, the writings of Charles Fourier "are a

glorious fuck you to all that exists" (Larsen 2011, 1) leaving a theory that took

at its heart the libidinal liberation of human passions. However, it was exactly

the passional character of his work which became omitted by his own scholars.

Subsumed under the notion of utopian socialism, we know that François

Marie Charles Fourier (1772–1837) has widely remained disregarded in his actual

contribution in trying to define a new philosophy of life. Beyond the fact that

himself did not consider his ideas ‘utopian’, his theory remained widely

misunderstood due to the phanstamagoric dramatization of a future world that

surrounds the core of Fourier's criticism. Even if Friedrich Engels applauded

that “Fourier has criticized existing social relations so sharply, with such wit

and humor that one readily forgives him for his cosmological fantasies, which

are also based on a brilliant world outlook.” (Engels 1845, 613), he truncates all

what was to heavy to swallow in one piece.

This has has shed a different light on Fourier's theory and the models

erected hereafter. Today Fourier is mainly acknowledged in regard to his

contribution to socialist thinking, but moreover as a precursor of Surrealism,

psychoanalysis, and as a proto-feminist, all of which his late biographer

Jonathan Beecher has greatly synthesized to liberate Fourier's a bit too crazy

work from his teleological appropriation and the smoothening objectification

by his scholars.

Fourier was utterly discomforted by the time and world he lived in. But his

work must precisely be understood in relation to his personal experiences in

his unglamorous life. Somewhat forced to become a merchant, he very early

developed a deep objection against the existing commercial system. After the

'catastrophe' of 1793, he was impoverished by the requisitioning of provisions

during the siege of Lyons by the Jacobins, then imprisoned and nearly deathsentenced after the fall of the city and enlisted for the army, the revolutionary

disorder left a deep disbelief in the new French society. He criticized the

absence of a lien général (general link) in civilized society. “In civilization

as a whole the interests of the people were separated from the progress

of the system itself, and in fact came to be in an inverse relationship to it”

(Riasanovsky 1969, 168).

Hence, with his first book Théorie des quatre mouvements et des destinées

générales (The Theory of Four Movements and the General Destinies ) which he

published anonymously in 1808, Fourier attempted nothing less than a critique

of civilization. In the epigraph of his preliminary discourse he centers his attack

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

On the stupidity of the civilized nations which have forgotten or scorned the two branches

of research which lead to the theory of destinies: the study of Agricultural Association and

the study of Passionate Attraction. And on the dire results of this stupidity which, for 2,300

years, has needlessly prolonged the period of social chaos, i.e. savage, barbaric and

civilized societies, which are far from being the destiny of the human race. (Fourier 1808

(1996), 5)

And civilization seemed to get increasingly worse within the emerging era of

industrialization. Early alarmed by the developing disciplinary and industrial

technologies that cause the societal fragmentation and the 'false fragmented

industry, repugnant and misleading', he reacted in a completely 'irrational'

sweeping blow assailing reason, the enemy of passion whose liberation

promised to him to unleash a world in universal harmony.

Inspired by Newton's law of gravitation or material attraction, Fourier claims to

have 'discovered' 2 the similar 'law' governing social interaction: “Attraction is

the active force of man as of matter”is how he would later put it more sharply 3 .

This principle leads him to conceive of a new social order based on passionate

attraction and attractive labor. Fourier described in detail a form of agricultural

association, organizing individuals for productive labor and all other activities,

where all passions would be liberated and fully satisfied. He eventually calls

this order the Phalanx4 and arrives at proposing a new form of settlement based

on this principle of association — the Phalanstère. 5

As is widely known, the Phalanstère was conceived as a unitary building

of equal magnitude to all royal palaces lodging self-contained communities,

ideally consisting of 1500-1600 people working together for mutual benefit.

In opposition to several readings, this form of 'association' must not be

confused with later socialist theories and cannot be considered a form

of collectivism or communism. 6

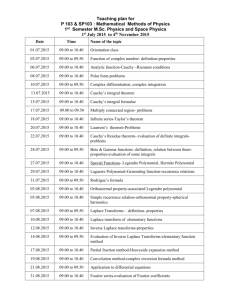

The most famous image was provided by one of his most trusted followers.

In his Description du Phalanstère (FN), Victor Considerant promotes the ideas

and its feasibility and offers an architectural vision derived from Fourier’s

sketchy plan. He “wanted to facilitate the understanding of a cooperative

building by means of a perspective” (ibid., 60. My transl. 7) illustrating that

“The cooperative (sociétaire) relationships lay down completely different

conditions for the architecture than those of civilized life. It is no longer to

build the proletarian slums, the bourgeois home, the hôtel of the speculator

or the marquis. It is the palace where MAN should lodge.”(ibid., 56 8) Since,

his 'de-contextualized' aerial view of the social palace bearing the bold caption

"L'Avenir" became thence the emblematic representation of Fourier's construct.

History has nonetheless proven, through the series of failed ambitions to

construct a phalanx9, that trying to embed a social theory into an architectural

object is a daring task. But Fourier's is also no longer a 'utopia' as Thomas

More's fabulation of an ideal state. Instead, he proceeds towards a dynamic

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

planning of development (Saage 1999, 73). In my opinion Fourier's ideas should

be seen from their aim to (re-)introduce something real into an increasingly

artificial, rational and modern world. This reading is influenced by the

contemporary French philosopher René Schérer, who started to re-approach

Fourier from a deleuzean perspective of our contemporary nomadic world:

Far from letting itself enclose, cloistered into a phalanstery as the utopian idea has too

long been interpreted, Fourier's plans made only sense if it occupied the entire planet that

it would cross/groove with industrial and amorous bands, to maintain on its surface an

incessant bustling motion. (Schérer 2009, 19. My transl. 10)

This encounter appears very powerful to rethink the production of built environment and social reality. Gilles Deleuze himself referred to Fourier sparsely

among the cornucopia of his references; except in Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and

Guattari's seminal critique of the repression of desires. Within their attempt

to theorize the 'machinic unconscious' Deleuze and Guattari emphasize that

"desire does not take as its object persons or things, but the entire surroundings

that it traverses [...] no one has shown this more clearly than Charles Fourier [...:]

We always make love with worlds.” (Deleuze&Guattari 1983, 293. emphasis added)

In their analysis of the relation between desire and social reality, Deleuze

and Guattari at once transgress the dualistic structure of sublimation posited

by freudian psychoanalysis ("fantasy vs. reality"), as well as re-write the marxian

historical materialism of society's modes of production by positing power

structures as an 'articulation of desires'. In a necessary mediation between

the two, based on Pierre Klossowski's aesthetics of embodiment, they how

'desiring-machines' are deeply related to production of social reality:

If we must still speak of utopia in this sense, à la Fourier, it is most assuredly not as an

ideal model, but as revolutionary action and passion. In his recent work [Such a Deathly

Desire] Klossowski indicates to us the only means of bypassing the sterile parallelism

where we can flounder between Freud and Marx: by discovering how social production

and relations of production are an institution of desire, and how affects or drives form part

of the infrastructure itself (Deleuze&Guattari 1972, 63 emphasis added)

To this extend we could say that Fourier's theory of passionate attraction was

"already anti-Oedipal, corresponding to Deleuze and Guattari's assertion that

desires don't belong to the realm of the imaginary" (Larsen 2011, 8)

If the relation between architecture and the construction of social reality is

understood in terms of a materialism of relations (physical, social, economic, ...),

it is precisely where Deleuze's notion of the 'machinic' comes into play to outline

a new model for the production of built environment beyond older forms of

representation. Today architects can reclaim the role of adventurous kybernétes,

navigating and exploring desiring-machines and regulatory systems, their

structures, constraints, and possibilities, to express and actualize them in

build form.

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

In the following, I will present a brief genealogy of the mediological role of architecture in relation to the production of social reality, by tracing the emergence of

modern space and the transition from a symbolic form of representation into what

within a deleuzo-guattarian vocabulary must be seen as a machinic articulation of

desire.

2.1 THE FORMATION OF A NEW ARCHITECTURAL DISPOSITIF

In earlier times of western architectural production, ‘tectonics’, understood

as the compositional analysis of structural features, offered the only applicable

model of representation. Tectonics are considered as the art of assembling

elements joint into a fixed structure. Therein tectonic elements idealiter

symbolize the role, or meaning, they possess within an well-composed edifice.

This role of architecture to represent these power structures has changed

in modernity. Architecture as an old medium of social hierarchies discovered

its potential to actually 'produce' society through build space. As an insight

derived from the application of poststructuralist theory 11 on the theorization

of social reality, this modern role of ‘ordering’ did only in the last 30 years gain

attention, specifically in terms of architecture’s compliance with biopolitical

apparatuses over the course European modernization.

Within his discourse analysis Michel Foucault’s archaeology of modern European society12 ignited an ongoing discussion on the formation of European

modernity. Seen from a general development starting from the seventeenth

century onwards — the management of state forces — he located in the

second half of the eighteenth century the emergence of an interrelated set

of mechanisms and technologies, which happened in a contingent, but rather

catalytic related development, within the modernization of western societies.

In his renown project, Foucault undiscloses an alteration in subjectivity

during the transition from the earlier sovereign societies into what he coined as

'disciplinary societies'. In Discipline and Punish the foundations of the political

theory are reformulated through his assertion that, unlike the 'judicial' power

of sovereign right, 'discipline' is concerned with the exertion of power on the

individual and his body. In complementing these ideas later he coined the

notion of "biopolitics", introducing an aspect in the analysis of power, where

we neither deal with 'society' (as the judicial body) nor with the individual/body.

What emerged in practice is the notion of a social body, or a population, as the

object of government; as a political and scientific problem; as a biological issue

of the exercise of power.

As soon as cities exceeded a certain limit, the threat of epidemics

endangered the functionality of the centers of economic activities. Under the

pressure to maintain public health, city governments have to develop strategies

of 'containment'. It is here, as Foucault pointed out, that a new model occurred

in which the feudal model of the 'imposition of death' is overtaken by a new

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

'governance of life' at the moment "the emergence of the health and physical

well-being of the population in general …[becomes] one of the essential

objectives of political power” (Foucault 2000, 94).

Subsequently, Giorgio Agamben radicalized these observations by

positing that modernity possesses such a fundamental biopolitical structure,

that it becomes the utmost defining character of modernity as such

(Agamben 1998, 181) more than any other criterion as i.e. the occurrence

of the nation state, industrialization or secularization.

2.2

THE DEFINITION OF MODERN SPACE

First and foremost, within the biopolitical rereading of modernity the problematization of architecture and the question what architecture does in all its

material and immaterial dimensions is first and foremost still not carried

out in all its details. But despite the growing body of analyses and theorization

concerning this (Foucault, Esposito, Lazzarato, Evans, Colomina, Hauptmann

(et. all.), Preciado) current practitioners seem, let's say, at least insensitive

to these utterly crucial premises for the creation of built environment.

Sven-Olof Wallenstein has based on Foucault rendered the up-to-now

clearest description of the relation between Biopolitics and the Emergenge of

Modern Architecture, where he illustrates how “Sometime during the latter half

of the eighteenth century, however, the classical models began to loosen their

grip. Architecture, we could say, started to withdraw from the model in the

sense of a representation of order, so as to itself become a tool for the ordering,

regimentation and administering of space in its totality.” (Wallenstein 2011, 20f.)

Thomas Markus moreover analyzed the production of social relations and

discipline in the formation of educational environments in his Buildings

and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types.

In a parallel line of thinking — but based on a more deleuzean, differencetheoretical account than Wallenstein — it is that German sociologist Heike

Delitz elaborates an assemblage-theory of a 'built society' (Gebaute Gesellschaft)

in which architecture constitutes “the medium of the social”. In her dissertation

she outlines how a city’s figuration actualizes the specific visible and tangible

“spatial organization or ‘configuration’, in and by which it makes that particular

society only effectually ‘existing’ in the first place.”(Delitz 2010, 123. my transl.)

Society is a becoming ‘under construction’, literally constructed through

architecture that fixes its each specific segmentation and hierarchies. In this

extended 'infrastructural' reading of built environment, architecture pertains

the role to mediate societies transitive shape..

Matthew Gandy's very recent exploration aimed to rethink "the spatial conceptualization of power developed by Foucault [...] by sketching an outline of the

emergence of biopolitical power and its relation with processes of social and

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

spatial exclusion." (Gandy 2012, 209&210) But in my opinion, these processes

of exclusion are not the spaces of exception as he depicts, or the exception

as such — but the contrary!

Where disciplinary society has produced the western ‘individual’ as a discrete

self13, along with an increasing organized modern world as an increasingly

complex system, 'modernity' in that regard appears as the attempt to implement a new representational or aesthetic paradigm when the notion of ratio shifts

its meaning from a relative ('proportion/measure') to an absolute understanding

('unit/ration/reason').

Accordingly, all modern phenomena regarding disciplinarization,

containment, interiorization, nationalization, rationalization, classification,

professionalization, labor division, exclusion, segregation, et cetera, cannot

be understood but from their common ground as technologies of enclosure:

"The process of modernization, then, in all these varied contexts is the internalization of the outside, that is the civilization of nature." (Hardt 1998, 141)

To help us understanding this process more systemically among the modern

spatial forms of control, Roberto Esposito wonderfully conceptualized

Luhmann's immunitary logic of modernization 14, offered with decisive

words worth being quoted at length:

What is immunization if not a kind of progressive interiorization of exteriority? [...]

Niklas Luhman was certainly the one who carried this logic to its extreme consequences.

Situated at the intersection of Parson's functional and the regulatory paradigm of cybernetic models, his theory constitutes the most refined articulation of immunitary logic as

a specific form of modernizatzion. Moreover he writes 'certain historical tendencies stand

out, indicating that since the early modern period and especially since the eighteenth

century, endeavors to secure a social immunology have intensified.' He also writes that

the immunitary system that originally coincided with what was extended to all spheres of

social life, from economics to politics. We see a tendency in Luhmanns' seminal definition

of the relationship between system and environment. There the problem of systematically

controlling dangerous environmental conflicts is resolved not only through a simple

reduction of environmental complexity but instead through its transformation from

exterior complexity to a complexity that is internal to the system itself. (Esposito 2013, 41)

From a spatial perspective (within a critical distance towards the modern mode

of architectural production), the larger portion of the processes of modernization

reads as an encompassing endeavor to define the world (a total organization)

into all kinds of enclosures, interiors and units. And even more recently this

continues as the world becomes virtually downsampled into digital 'bits'.

However, this digitalization has helped to invigorate a new form or system

of governance.

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

2.3

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

NEW RELATIONS IN DIVIDUALIZING NETWORKS

Furthermore, we have to consder that the problematique of architecture's

compliance with biopolitical apparatuses might have only come to our attention,

as there is a transition taking place, in which this predominant model becomes

replaced by something else! As Deleuze presciently described in his "Postscript

on Societies of Control", the process of organizational division itself draws to a

close:

We are in a generalized crisis in relation to all the environments of enclosure —

prison, hospital, factory, school, family. [...] But everyone knows that these institutions are

finished, whatever the length of their expiration periods. It's only a matter of administering

their last rites and of keeping people employed until the installation of the new forces

knocking at the door. These are the societies of control, which are in the process of

replacing disciplinary societies. 'Control' is the name [William] Burroughs proposes as

a term for the new monster, one that Foucault recognizes as our immediate future.

(Deleuze 1992, 3f. my emphasis)

A decisive factor heralding the emerging diagram of control, is certainly

the occurrence of the world-wide webs that extend the panoptic diagram

of surveillance into a more synoptic meshwork of control mechanisms.

Beyond the morphological understanding of the Network Society trumpeted

by Manuel Castells' 15 in which communication and infrastructural "spaces

of flows" become (or rather remain) the key organizing (!) factors in the world

economy, todays situation is more crucially characterized by the cultural impact

of those networks. After the necessary infrastructures and networks to sustain

the global economies and everyday flows of resources, debris, electricity and

communication are erected; after the dawning digitalization of the world,

we are facing today a reversal of the modern model shaping a completely

U-turned form of subjectivity.

The internet first of all accelerated, and somewhat facilitated a means to

productively use social relations and knowledge exchange. But furthermore

it triggers new habits to think production in terms of agency and networking,

by launching new modes of subjectivation regarding Varnelis' notion of a newly

emerging form of "network culture". In the recently developed age of networks,

global economy, informatization, etc, we observe the generation of a new mode

of existence. He emphasizes that

During the space of a decade, the network has become the dominant cultural logic.

Our economy, public sphere, culture, and even our subjectivity are mutating rapidly

and show little evidence of slowing down the pace of their evolution.[...] Network culture

extends the information age of digital computing. [...] To understand this shift, we can

usefully employ Charlie Gere’s insightful discussion of computation in Digital Culture.

[... that as] he observes, is fundamentally based on a process of abstraction that reduces

complex wholes into more elementary units. [...] But today connection is more important

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

than division. In contrast to digital culture, under network culture information is less

the product of discrete processing units than of the outcome of the networked relations

between them, of links between people, between machines, and between machines and

people. (Varnelis 2008, 145-6. Emphasis added)

Varnelis outlines emphasizes that information, being less the product of

discrete processing units, is produced through the networked linkage between

them: between people, between machines, and between machines and people.

"In network theory, a node's relationship to other networks is more important

than its own uniqueness. Similarly, today we situate ourselves less as individuals and more as the interstices of multiple networks composed of both

humans and things.”(Varnelis 2007, n.p.)

Here Varnelis develops further an idea on what Deleuze could barely make

out the picture in his Societies of Control. For Deleuze the contem-porary self is

not so much constituted by any notion of identity but “Individuals have become

dividuals” (Deleuze 1992, 5), which means, they have become human subjects

that are endlessly divisible and reducible to data representations via the modern

technologies of control, and subjects that are caught up in a process of constant

‘modulation’. 16 The way Varnelis reads this, is crucial for architectural discourse,

when he shift the focus away from the diagram of control to the construction

of networks, which become the constituent environment for the dividual subject .

Thence, what would be a new agenda for architecture, if built environment

literally matters as the physicality of how we relate (or the actualization of

our relations) to each other? And, to bring this a step further, what if we even

radicalize dividual subjectivity, from the perspective of a 'radical relationality'

(Protevi) saying that through networks, we do not even have relations anymore:

The relationship between the 'individual' and its 'environment' in networked

systems becomes so extensive, that it almost overstates the distinction between

dividual and networks to speak of a relation at all. 17 All relations become primary

to the relata which become only nodes.

In order to approach a mediological conceptualization of dividual-networked

built environment this regard, this new model might first be roughly circumscribed as a facilitation of relational connections in order to create new spaces

of association that break up the disciplinary processes of interiorization and the

carve-up of the modern world. It is here, where I want to conclude by going back

to my initiating discussion of Charles Fourier.

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

3 REREADING FOURIERS DESIRING-MACHINES

Le Corbusier, who was strongly influenced by Fourier’s machinic thinking, 18

claimed in his rhetoric how to think of the modern city and the development

of architecture dating back, the persistence of "certain prophetic propositions of

Fourier, formulated around 1830, at the time when the machine itself was born.”

(Le Corbusier 1945, 44) This contextualization of Fourier's ideas in the emerging

machine age is quite revealing as “Fourier himself was deeply interested in the

newly emerging machines of his own time, and aimed to create a world order

patterned on them.” (Serenyi 1967, 279). But as we have seen those are not the

mechanistic conceptions of the apparatuses of disciplinarization, that produce

enclosures. Instead is was a counter-paradigm fighting the ongoing processes

through radical facilitation of association and attraction.

We are asked to finally recognize that machines are primarily systems that

accumulate energy surpluses and hence it become much more crucial how

they consume, transform and dissipate it. This energy is thus any form of

potentiality, electricity, data, information, knowledge, labour, money, desire.

Therefor "Any system should be defined by the excess of energy operating it."

(Pasquinelli 2013, 69). And since Deleuze and Guattari have exercised in

A Thousand Plateaus that any machinic articulation is always a "double

articulation", we have to divide (as Pasquinelli points out) on one hand hand,

the flows, networks and productions (forms of expression, constitutive actualization, agencements) of desires and on the other the codes, media and representations (forms of content, constituted/constituting possibilities, Gestalt)

of the articulation itself.

This affective, libidinal, passionate or energetic turn in understanding

systems is a precondition for a new materialism of relations. By reading

'infrastructure' or networks beyond their dominant conception as a connective

superstructure, it presents instead the ultimately affirmative form of machinic

association: We can no longer understand infrastructure and networks in terms of

the flows it controls and 'contains' — but only in terms of the flows it 'produces'

or sets in motion!

Being somewhat untimely, the Phalanstère did not pose the right question at

its time, maybe since it didn’t contain the problem anymore. The Phalanstère

presented an architecture that addresses a problem outside of it and tried

to set free a new form of subjectivity, given that “the edifices that Fourier had

envisioned [...] would bring about a world in which every human being would

be turned into a vagabond rootless and lonely — just like Fourier himself.”

(Serenyi 1967, 282)

Each Phalanstery would have been an infrastructural nodes in a system

of phalanxes. From todays perspective we can understand the Phalanstère

as a nomadic utopia. To that extend the Phalanstère is less of a typical

'utopian vision'; it is just a perfect machine — one that nobody wanted.

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

The build environment that would facilitate a form of life based on Fourier's

theory of passionate attraction could have introduced a sudden change in the

operational direction of industrialization and thus the mode of modernization,

envisaging a peripeteia, that today seems unavoidable in our networked,

globalizing world, its post-fordist knowledge economy and its uprooted,

nomadic subjects.

Robert A. Gorny (Juli 2012, Delft)

WORKS CITED:

–

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer, Sovereign Power and Bare Life,

transl. Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

–

Bey, Hakim."The Lemonade Ocean & Modern Times."

Accessed http://library.uniteddiversity.coop/More_Books_and_Reports/

The_Anarchist_Library/Hakim_Bey__The_Lemonade_Ocean___Modern_Times_a4.pdf

–

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society, The Information Age:

Economy Society and Culture, Vol. I. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

–

Considerant, Victor. Description du phalanstère et considérations

sociales sur l’architectonique. 2e éd, rev. et corr. Paris 1948.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, gallica.bnf.fr.

Accessed http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k101915g

–

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus, Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

Transl. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983 (2000¹º).

–

Deleuze, Gilles."Postscript on the Societies of Control". October, Vol. 59 (Winter 1992), 3-7.

–

Delitz, Heike. Gebaute Gesellschaft. Architektur als Medium des Sozialen. Frankfurt/M.,

New York: Campus, 2010.

–

Engels, Friedrich. A Fragment of Fourier’s On Trade, in: Marx/Engels Collected Works,

Volume 4. Accessed: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/09/fourier.htm

–

Foucault, Michel. "The Politics of Health in the Eighteenth Century."

Foucault, Michel. Power. Essential Works of Foucault, 1954.1984, Volume 3,

ed. James D. Faublon. New York: The New Press, 2000: 90-105.

–

Fourier, François Maria Charles (publ. anon.). Théorie des quatre mouvements et

des destinées: prospectus et annonce de la découverte générales. Leipzig: Pelzin, 1808.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, gallica.bnf.fr.

Accessed http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k106139k

–

Fourier François Maria Charles. Theory of the four movements, ed. Gareth Stedman Jones

and Ian Patterson; transl. Ian Patterson. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1996.

–

Fourier, Charles. "Le nouveau monde industriel et sociètaire" (1848). Fourier, Oeuvres

complete, Vol. VI, 26. Accessed http://archive.org/stream/

uvrescompltesde01fourgoog#page/n9/mode/2up

–

Gandy, Matthew. "Zones of Indistinction: Bio-political Contestations in the Urban Arena."

Architectural Theories of the Environment: Posthuman Territory,

ed. Ariane Lourie Harrison. New York: Routledge (Taylor&Francis), 2013.

–

Hardt, Michael. "The Global Society of Control" Discourse 20.3, Fall 1998: 139-152.

–

Larsen, Lars Bang. Giraffe and Anti-Giraffe: Charles Fourier's Artistic Thinking. e-flux

journal #26, june 2011. Accessed http://worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_8888237.pdf.

–

Le Corbusier. Manière de penser l’urbanisme.

Paris: Éditions de l'architecture d'aujourd'hui, 1946.

–

Pasquinelli, Matteo. "The Biosphere of Machines: Enter the Parasite".

Architectural Theories of the Environment: Posthuman Territory,

ed. Ariane Lourie Harrison. New York: Routledge (Taylor&Francis), 2013.

–

Protevi, John. "Deleuze and Wexler: Thinking Brain, Body and Affect in Social Context."

Cognitive Architecture. From Biopolitics to Noopolitics. Architecture & Mind in the Age of

Communicatin and Information, eds. Deborah Hauptmann and Warren Neidich.

Rotterdam: 010 Publishers 2010: 168-183.

–

Riasanovsky, Nicholas Valentine. The Teaching of Charles Fourier.

Berkeley and Los Angeles: Unversity of California Press, 1969.

–

Saage, Richard. “Utopie und Eros, Zu Charles Fouriers ‘neuer sozietärer Ordnung’."

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

UTOPIE kreativ, H.105 (Juli) 1999: 68-80. Accessed

http://www.rosaluxemburgstiftung.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/105_Saage.pdf

Schérer, René. Utopies nomades. Paris: Les presses de réel, 2009

Sérenyi, Péter. "Le Corbusier, Fourier, and the Monastery of Ema". The Art Bulletin,

Vol. 49, No. 4 (Dec., 1967): 277-286. Accessed http://www.jstor.org/stable/3048487

Varnelis, Kazys. "Conclusion: The Meaning of Network Culture."

Networked Publics, ed. Kazys Varnelis. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008: 145f.

Varnelis, Kazys. "The Rise of Network Culture" (2007).

Accessed http://varnelis.net/the_rise_of_network_culture

Wallenstein, Sven Olof. Biopolitics and the Emergence of Modern Architecture.

New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

Wexler, Bruce "Brain and Culture: Neurobiology, Ideology and Social Change."

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006.

Williams, Robert W., "Politics and Self in the Age of Digital Re(pro)ducibility.",

Fast Capitalism, Vol. 1.1 (2005).

Accessed http://www.uta.edu/huma/agger/fastcapitalism/1_1/williams.html

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

1

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

In the 20th century a large body of theories has emerged that attempts to understand

development/physical creation/form-giving/ordering principles altogether less causal

and teleological, but more anti-humanistic and non-intentionally as to grasp them as

processes of self-generated form. Without diving into a genealogy of the 20th century

theories accounting self-organization or emergence in complex systems, let me oversimplify them to search for internal (automatic, systematic or immanent) laws that

‘attract things to come together to produce something new’.

2 "Is it as a result of contempt, oversight, or fear of failure that scientists have neglected the

problem of association? The motive does not matter; the fact is that they have neglected it:

I am the first and only one to have concerned myself with it." (Fourier 1808 (1996), 15)

3 Fourier 1848, Vol. VI, 26

4 French: 'Phalange', from greek phalanx, was a rectangular mass military formation.

Fourier initially pondered in his naming and called the formation initially also 'le

tourbillon'. The name refers the elitist corps of people but as well to the serial interrelationship of elements of the finger bones, which have been named after the battle

formation.

5 "The first science I discovered was the theory of passionate attraction. When I realized

that the progressive Series would ensure that everybody's passions were fully developed,

irrespective of sex, age or social class, and that in the new order these increased passions

would bring with them commensurately greater health and strength, I conjectured that if

God had given so much influence to passionate attraction and so little to its enemy,

reason, it must be in order to lead us to the order of the progressive Series in which all

aspects of attraction would be satisfied. This led me to suppose that attraction, so scorned

by the philosophers, was the correct way to interpret God's views about the social order.

Thus I arrived at the analytic and synthetic calculus of passionate attraction and repulsion, which in turn leads ineluctably to agricultural association." (Fourier 1808 (1996), 15)

6 It is essential to Fourier that association is not strictly 'egalitarian,' and neither does he

aim to eliminate personal property or inheritance for he is precisely arguing that dissent

is much more constitutive for social harmony than any a priory determined homogeneity.

He explicitly kept on criticizing Owen exactly for his non-competitive systems, polemicized

that the idea of community of property was 'pitiable'.

7 Ibid., my translation, orig.: “J’ai voulu faciliter l’intelligence

d’un édifice sociétaire, au moyen d’une perspective”

8 Considerant, Victor. Description du phalanstère et considérations sociales sur

l’architectonique (2e éd, rev. et corr. Paris 1948) Bibliothèque nationale de France

gallica.bnf.fr. Accessed http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k101915g

My translation, orig.: “Les relations sociétaires imposent donc à l’architecture des

conditions tout autres que celles de la vie civilisée. Ce n’est plus à bâtir le taudis du

prolétaire, la maison du bourgeois, hôtel de l’agioteur ou du marquis. C’est le palais

ou l’HOMME doit loger.”

9 In 1832 Fourier attempted to create a trial phalanx in Condé-sur-Vesgre as J. Beecher (1986)

describes. He rejected an initiative to build a Phalanstery near Rambouillet for it did not

match his ideas. Other attempts to build Phalansteries in Algeria and the United States

failed as well. Even before Robert Owen (the Welsh industrialist and social reformer,

that Fourier polemicized against) purchased the town of Harmony (Indiana) in 1825

with the intention of creating a new utopian community and renamed it New Harmony.

However Owen's social experiment failed economically just two years after it began."

(http://www.examiner.com/article/new-harmony-a-utopian-experiment-the-americanwilderness). Albert Brisbane did a great deal to popularize Fourierism in the United States.

On an invitation by Brisbane and helped by Jean-Baptiste Godin (who in 1858-1883 built

the Familistère in Guise, however with radical architectural an social changes to the

original concept), between 1855-57 he founded the colony La Réunion in Texas on

Fourier's principles. Later several phalanxes were founded in the states — however none

even equalled Fourier initial architectural ideas. Among the most popular are: La Réunion

was a socialist utopian community formed in 1855 by French, Belgian, and Swiss colonists

near the forks of the Trinity River in Texas, USA; the North American Phalanx (NAP)

was a secular Utopian community located in Colts Neck Township, in Monmouth County,

New Jersey, 1943-56; the Raritan Bay Union was a utopian community in Perth Amboy,

New Jersey from 1853 to 1860; the Community Place, in Skaneateles, New York was built

in 1830; Alasa Farms, also known as the Sodus Bay Shaker Tract and Sodus Bay Phalanx,

is a historic farm complex located near Alton in Wayne County, New York; Brook Farm;

Oneida Community; Bishop Hill, Illinois; the Icarians communities.

10 orig. “Loin de se laisser enclore, comme on l'a trop longtemps interpretée, dans le cloître

d'un phalanstère, elle n'a des sens que par l'occupation de la terre entière qu'elle sillonne

avec des bandes industrielles et amoureuses, entretenant à sa surface un incessant va-etvient.”

The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design

Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft

Robert Alexander Gorny

Seminar F.Geerts, 2013

11 This model of thought requires a 'flat' analysis of both the object itself as well as the knowledge that has produced that object. When the growing field of language studies started

questioning these meanings and the logical structures and how symbolism is constituted

and how they can be understood at all. After linguistic theory posited how elements must

be understood in relation to their embedding or overarching system, subsequent structuralist theories argued that human culture in general may be understood by means of

a structure. As a matter of fact thinkers very soon started to reject the assumed selfsufficiency of any those structures that structuralism posits and they start interrogating

the binary oppositions (like signifier/signified) that constitute those ‘structures’. With this

reversal marking the transition from structuralism to post-structuralism, the theorization

of the constitution of social reality necessitated to increasingly move away from objectivist perspectives. Subsequently cultural, philosophical and other critical theories were

developed by inverting the dominance and representational structure into more selfconstitutive ways of thinking. Post-structuralism is therefor a confusingly complex attempt

to theorize how elements in a system shape, influence and determine the system itself by

means of epistemic experimentation to construct new systems and models of thought or

expression in themselves.

12 The related primary works in which the formulation of disciplinary societies and

biopolitics take shape are Michel Foucault: The Birth of the Clinic (orig. published Presse

Universitaires de France, 1963). (Oxon: Routledge, 1989); Disciple and Punish, The Birth

of the Prison (orig. published Éditions Gallimard 1975). Transl. Alan Sheridan (London:

Penguin Books, 1979); and furthermore the lectures collceted in The Birth of Biopolitics,

Lectures at the College De France, 1978-1979, (orig. published Éditions du Seuil/Gallimard

2004). Ed. Michel Senellart, transl. Graham Burchell (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan,

2008) and Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France 1977-1978

(orig. published Éditions du Seuil/Gallimard 2004). Ed. Michel Senellart, transl.

Graham Burchell (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007)

13 Framed in the developing liberal idea of freedom "The individual in Western philosophical

and political theories, especially after René Descartes, is theorized as the discrete self.

That is to say, the essential part of the individual is the self, the unique and fundamentally autonomous entity in Western value systems. As analyzed by various conventional

Western social sciences, the self is fundamental to our humanity: it is how we organize

our personal experiences and it is the basis for our reflexive action in the world."

(Williams 2005. n.p.)

14 See Roberto Esposito, Bios: Biopolitics and Philosophy (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 2008) and Terms of The Political, Community Immunity, Biopolitics

(New York: Fordham University Press, 2013)

15 Castells explicitly start to theorize networks from an urban perspective. He observes that

"Our societies are constructed around flows: flows of capital, flows of information, flows

of technology, flows of organizational interactions, flows of images, sounds and symbols.

Flows are not Just one element of social organization: they are the expression of the

processes dominating our economic, political, and symbolic life. [...] Thus, I propose the

idea that there is a new spatial form characteristic of social practices that dominate and

shape the network society: the space of flows." (Castells 1996, 412)

16 Gilles Deleuze 1992, 5: "The disciplinary societies have two poles: the signature that

designates the individual, and the number or administrative numeration that indicates

his or her position within a mass. This is because the disciplines never saw any incompatibility between these two, and because at the same time power individualizes and masses

together, that is, constitutes those over whom it exercises power into a body and molds the

individuality of each member of that body. (Foucault saw the origin of this double charge

in the pastoral power of the priest-the flock and each of its animals-but civil power moves

in turn and by other means to make itself lay 'priest.') In the societies of control, on the

other hand, what is important is no longer either a signature or a number, but a code:

the code is a password, while on the other hand the disciplinary societies are regulated

by watchwords (as much from the point of view of integration as from that of resistance).

The numerical language of control is made of codes that mark access to information, or

reject it. We no longer find ourselves dealing with the mass/individual pair. Individuals

have become 'dividuals,' and masses, samples, data, markets, or 'banks.'"

17 Wexler 2006, 39. Cited after: Protevi 2010, 174

18 Peter Serenyi “Le Corbusier, Fourier and the monastery of Ema” (1967): Peter Serenyi

profoundly illustrated the relationship between two man, as Corbusier which not only

evidences in Corbusier's dictum of the 'machine for living in' but also how he develops

the idea of his eminent Unité d'habitation.