Now or Never – Final Report

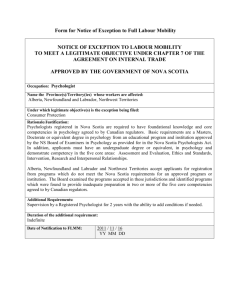

advertisement