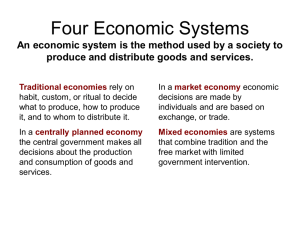

New urban economies: how can cities foster economic development

advertisement