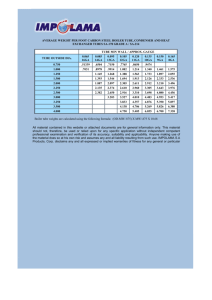

Steel Tube and Pipe Manufacturing Process

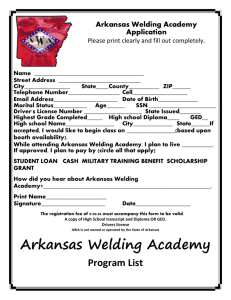

advertisement