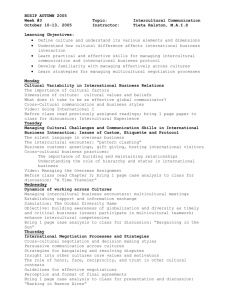

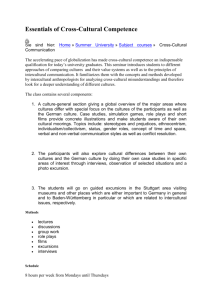

Social Psychological Concepts in the Context of

advertisement