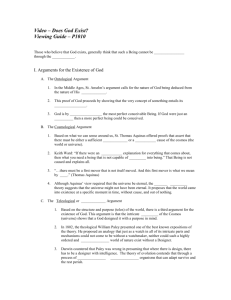

Arguments for the existence of God

advertisement

1

Metaphysics: Arguments for the existence of God (Prof. Peter Clark)

Introduction to the Design, or Teleological, Argument

Part One

The Design Argument for God's Existence

The design argument for the existence of God is very ancient. It occurs in the famous late Dialogue of

Plato (427-347 B.C.) the Laws. One of the characters therein asks Cleinias how he would establish for

the barbarians the existence of the Gods. Cleinias replies:

“How? In the first place, the earth and the sun, and the stars and the Universe, and

the fair order of the seasons and the division of them into years and months, furnishes proofs

of their existence; and also there is the fact that all Helenes and barbarians believe in them”.

(Book X Laws).

Certainly Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) deployed it. He wrote:

“ ......... so those who first looked up to heaven and saw the sun running its race from

its rising to its setting , and the orderly dances of the stars, looked for the craftsman of this

lovely design, and surmised that it came about not by chance but by the agency of some

mighty and imperishable nature, which was God.” (Aristotle, Selected Fragments, Vol. XII of

The Works of Aristotle, Ed by W.D. Ross.)

Sextus Empiricus (Third century B.C.) our source for the great tradition of Pyrrhonian skepticism

(there is no such thing as positive knowledge), wrote as follows:

And just as the man who is familiar with ships, as soon as he sees in the distance a

ship with a favouring wind behind it and with all its sails well set, concludes that there is

somebody who directs its course and brings it into its appointed havens, so too those who

first looked up to heaven and beheld the sun running its courses from East to West and the

orderly processions of the stars sought for the artificer of this most beautiful array,

conjecturing that it had not come about spontaneously but by some superior and

imperishable nature, which is God. (Outlines of Pyrrhonism, Vol. I).

The school of Greek philosophy known as Stoicism, founded in the Third Century B.C., was much

influenced by the order and symmetry of the World, by Roman times it was one of the most

influential intellectual doctrines of the civilised World. The great Roman Stoic thinker Cicero wrote

in De Natura Deorum

“with what possible consistency can you suppose that the universe which contains

these same products of art [Statues houses, water clocks], and their constructors, and all

things, is destitute of thought and intelligence”

St. Thomas Aquinas in his monumental Summa Theologicae, written between (1265-1273), used it as

one of the five proofs of the existence of God. He uses the argument principally to establish how we

can come to have knowledge of the perfection of the divine being. He wrote:

“But since our intellect knows God from creatures, in order to understand God it

forms conceptions proportioned to the perfections flowing from God to creatures.”

(Summa Theologicae, Part 1, Question 13)

However we will begin systematic study of the argument by examining the form of it due to William

Paley (1743-1805) in his Natural Theology (1803). Paley argued as follows:

2

“Suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there:

I might possibly answer, that, for anything I knew to the contrary, it had lain there forever; nor would it,

perhaps be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I found a watch upon the

ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place. I should hardly think of

the answer I had before given - that, for anything I knew, the watch might always have been there.

Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? When we come to

inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are

framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce

motion, and that motion is so regulated as to point out the hour of the day.

Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch,

exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater and more,

and that in a degree which exceeds all computation. I mean, that the contrivances of nature surpass

the contrivance of art, in the complexity, subtlety, and curiosity of the mechanism.”

So Paley's argument is essentially this: we infer correctly that the watch is an instrument with a

purpose, a designed artefact which fulfils a purpose. Now the Universe has a complexity in

contrivance infinitely greater than the simple mechanism of the watch, so too with Nature we should

conclude that Nature is no fortuitous accident but constructed in the light of a design by a designer,

viz. God. Paley's argument is then essentially a design argument and a teleological argument, the

Universe is complex and superbly integrated, exhibiting a design, it also serves a purpose or an end

(to sustain us and bring us to salvation) just like the watch does in telling the time.

A similar point is made by Hume in his exposition of the argument:

“Look round the World: contemplate the whole and every part of it: you will find it to be

nothing but one great machine, subdivided into an infinite number of lesser machines, which

again admit of sub-divisions to a degree beyond what human senses and faculties can trace

and explain. All these various machines, and even their most minute parts, are adjusted to

each other with an accuracy which ravishes into admiration all men who have ever

contemplated them. The curious adapting of means to ends, throughout all nature, resembles

exactly, though it much exceeds, the production of human contrivance: of human designs,

thought, wisdom and intelligence. Since therefore the effects resemble each other, we are

lead to infer, by all the rules of analogy, that the causes also resemble; and that the Author of

Nature is somewhat similar to the mind of man, though possessed of much larger faculties,

proportioned to the grandeur of the work he has executed. By this argument a posteriori, and

by this argument alone, do we prove at once the existence of a deity, and his similarity to

Human mind and intelligence.” ( Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion)

Before embarking on a critical study of the argument let us tell a little story.

Suppose that as we wander along a beautiful beach of white sand and rolling surf we come upon a

disturbance in the otherwise uniform expanse of the sand beach. On further investigation we discover

that the disturbance in the sand is actually a sequence of interpretable signs, in fact, let us say that the

disturbance can be read as the English sentence “Coca-Cola Rules”. A natural response to this

discovery would be to think that before we had trod this fair shore some person had, perhaps with a

stick, traced out the legend. The disturbance after all is intelligible, has clear content (meaning) and

(let us presume) is executed with calligraphic style. So from the presence of a message, from the

presence of an imprint so redolent with purpose and design we naturally conclude that it was designed

to fulfill a purpose by a person.

Is this conclusion justifiable? - Is it reasonable? Certainly, just as it stands, it would surely not

be a reasonable conclusion. For it is well known that waves pounding a beach, coupled with sea

breezes, can produce all manner of delicate patterns and complex configurations of shell and sand.

There is absolutely nothing in the laws of physics which forbids that the mechanical and thermal

action of wind and sea should not produce by what we deem to call fortuitous accident just that

distribution of sand particles which generate the physical form of the letters “Coca-Cola Rules”. Such

a distribution of particles arrived at in this way would no doubt be regarded as highly improbable,

indeed as being so improbable as to be ruled out. But this thought must be treated with some care, for

3

improbable events do occur and we must ask ourselves what it is that renders such a configuration so

highly improbable, that it is effectively ruled out?

To answer these questions requires, if it is to be done properly, a considerable amount of

sophisticated physics and statistics. For our purposes however all we need to note is that from our

knowledge of the laws of Nature (i.e. namely how Nature works) we can legitimately reason that the

beach has been interfered with. Thus the conclusion that the sign represents the work of a person in

advertising or at least of someone spontaneously expressing a strong preference, is based upon the

existence of a standard of comparison, upon a way of assigning probability to various classes of

events, in short to the existence of a probability metric. In effect it is an argument by analogy, the

analogy being guaranteed by a standard of comparison - by what we know of what Nature alone can

produce and what we can produce by intentional design. That this probability measure or standard of

comparison is indeed well-founded is guaranteed as a consequence of a particular physical theory, a

theory which moreover has a very high degree of empirical support. The conclusion that should be

stressed is that the probability ascriptions or the analogies with what we commonly find made in this

case and examples like it depend ultimately upon physical theory (or at least common sense and

general knowledge of the way the World is.).

If we compare the stages of Paley's account of stone-watch-Nature, with our story of the walk

along the beach we obtain something like the following three stages: uniform flat beach - ‘Coca-Cola

Rules’ - Nature. We there noticed that the transition from uniform flat beach - requiring no designer

or intervention - to recognising ‘Coca-Cola Rules’ as requiring a person as executor of the sand

message, required special premises involving appeal to a physical theory which allowed for a

standard of comparison to be made as to the likelihood of a spontaneous production of the sign to its

production by someone playing on the beach. What additional premises are invoked in Paley's

argument? The answer is none - and there lies the real gap in his argument. The mere perception of

complexity in the watch or the message will not suffice for, as was said, it is very well known that

Nature quite spontaneously produces very complex and intricate patterns and mechanisms (that surely

is the whole import of the Darwinian theory of evolution by natural selection and random variation).

In order to correctly infer the existence of a designer we needed to have an argument which shows

that the particular sort or type of complexity exhibited by the object in question could not (or could

not except with extreme improbability) be produced spontaneously in nature.

The immediate reply might be that this can trivially be done for Paley's argument, for surely

it cannot be suggested that watches could be spontaneously produced by the fortuitous combination of

suitable molecules? Indeed not, but two points should be noticed: 1) that some theory or standard of

comparison is required to supplement the step from ‘complexity’ to ‘designed’ and 2) no plausible

theory is going to do the job when we make the analogous step for the Universe (or Nature) as a

whole. There are after all no other Universes with which we are acquainted against which we may

compare this one, no probability estimates (because there is no corresponding sample space, the

Universe is unique) on which we may base our conjectures about the likelihood of our Universe being

brought about in differing ways. So unlike every other case of the ascription of artefact and design on

the basis of comparison with some standard, by the very nature of the case when applied to the

Universe as a whole no such straightforward comparison is possible.

This point is due (in a slightly different form) to the great Scots philosopher David Hume

(1711-1776) in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779). Hume makes the following

devastating points in respect of the soundness of the design argument, which apply equally well to

Paley's argument, though it was published before Paley wrote. (i) The World is one particular, not a

member of a species or collective. (ii) As such there is no evidence of any sort of a constant

conjunction between order and design. (iii) The analogy argument won't work; for every purported

analogy between design and perfection or good order found in the World, there is another from the

profound lack of order and chaos found in the World to the lack of a designer. (iv) To quote Hume

"For all we know a priori, matter may contain the source or spring of order originally, within

4

itself...."; eighty years later in 1859 Charles Darwin published the first edition of The Origin of the

Species and almost 100 years after that Watson and Crick discovered the structure of DNA, the

molecular basis of life.

Part Two

Above we considered a traditional form of the Design Argument, that of William Paley. There we

found that the very step at which the argument gets going, from complexity infer design, there is a

huge gap in the reasoning. In order to mediate the move from complexity to design we need a

premise which tells us how to sort out artificially contrived designed complexity, from complexity

arising out of ordinary natural processes according to the laws of Nature. In short we need a standard

of comparison. But just because Paley wants his argument to apply to the Universe as a whole, we

can’t have a standard of comparison, there simply aren’t any other ‘Universes’ to compare with this

one. So the argument collapses.

Perhaps a defender of the design argument could seek to fill in this gap. There is a wellknown attempt to do so in an extension of the design argument called the argument from

improbability.

An Argument from Improbability

There is, of course, no difficulty in principle in the idea that one can form a set of ‘Universes’ by

thinking of all the different ways in which the laws of Nature could be true (i.e. in forming the

collection of all the ways in which the laws of physics could be true, of all physically possible

worlds). But this will not do as a reference class because we want to consider not the class of all

Universes which have the same laws of nature that ours does, but the class of all possible Universes.

There is however a way of thinking about the latter, which involves considerable idealisation but

which can be employed to illustrate the point a proponent of the design argument may make here.

Replace the set of all possible Universes with the set of all sequences whose members are

zeros and ones. (One can think of a “Universe” as just one such sequence). The characteristic

appealed to in the design argument is the complex but highly ordered and integrated nature of our

own Universe. The corresponding characteristic in the set of sequences, will be shared by the ordered,

or law-like non-random sequences as opposed to the random sequences.

Now it can be shown mathematically (how need not concern us) that there are very many

more random chaotic sequences than law-governed ones. Hence it might be argued if we take the set

of all possible Universes (or in our idealised case all sequences) the chance of finding an ordered one,

by arbitrary selection, will be zero. The Universe we find ourselves in is, it seems, in that it allows for

the existence of human beings, certainly ordered and structured to some degree so it must be a special

case. Indeed, it is so special a case as to require an explanation, and that explanation has to involve

the existence and intervention of God. It cannot have arisen by chance alone – by arbitrary selection.

This argument, however plausible it may appear, does not work. First, the fact that ordered

sequences (or ordered ‘Universes’) have prior probability zero, certainly does not mean that such an

ordered sequence could not result from one arbitrary selection (or could not occur). An event having

probability zero does not mean that it will not occur. That is the first point we should note.

A second very important point is this: What probability we assign to an event (the Universe

being an ordered one, for example) depends crucially upon how that event is described. Now this is

important because a proponent of the design argument must show not only than an ordered Universe

has low probability, but that probability is so low as to require a special explanation as to why that

low probability has been actualised, i.e. why that low probability event has come about. The special

5

explanation employed is of course that God designed or created the Universe. Let’s examine this

point with a simple example.

Suppose that there are four players of a card game and each is dealt a hand of thirteen cards.

Player A looks at each of the cards as they are dealt and wonders at the miraculously low–probability

of the event which is occurring before his eyes, viz., that he should be dealt just thus and so a hand, in

just that particular order. If we look at the prior probability of obtaining A’s hand, in just that order,

then indeed the probability of obtaining that particular hand is very low. Nonetheless A must receive

some hand and every particular hand has the same low probability. Hence his receiving the hand he

does requires no special explanation at all, over and above the explanation that obtains for all the

hands dealt, namely, that they are determined by the order in the pack after shuffling and the manner

in which the cards are dealt. No special explanation requiring some design or conspiracy is required

to explain the occurrence of that very event, despite its low probability, that A obtained the particular

hand he did, in that particular order.

So the most that the argument we have been considering can establish is the low prior

probability of the existence of an ordered Universe, but it can do nothing to establish or make

probable the existence of God, as a creator of such a Universe. For we have yet to see a reason for

thinking that the admittedly low prior probability ordered Universe, is a low probability “event”

requiring special explanation.

A third difficulty for the argument concerns the fact that it ignores a possibility, a possibility

we have very good reason to believe is actually realised. The argument has as one of its premises that

our Universe is ordered, obeying definite (if often only statistical) regularities. This is no doubt right.

But the argument also assumes that this order was present at the origin of the Universe, for the

problem is to ‘select’ an ordered sequence (‘Universe’) from the collection of all sequences

(‘Universes’). But this neglects a possibility, viz., that highly ordered states can arise via the operation

of ordinary physical law from highly disordered or chaotic initial states. In other words, the highly

ordered Universe of the present epoch could have evolved from a highly chaotic disordered initial

state. If this were the case, then it is quite wrong to attempt to ascertain the prior probability of

finding an ordered sequence or Universe, by looking at the subclass of ordered sequences in a class of

all sequences, for in doing that, we would be neglecting the class of cases in which ordered states

evolve from initially disordered ones.

Modern cosmology informs us that there is a very good reason to believe that this possibility

actually has been realised in the case of the evolution of our Universe. According to generally

accepted cosmological theories, very close to the origin of the Universe (very, very shortly after the

‘Big Bang’) the state of the Universe was that of thermodynamic equilibrium – the most highly

‘disordered’ state conceivable. Two factors however then operated which were sufficient to transform

the uniform equilibrium into a highly ordered cosmos, viz., gravitation and the expansion of the

Universe. The operation of both these constraints, the existence of a gravitational field and the

expansion of the Universe, induced temperature differences sufficient to destroy the initial

equilibrium state thus inducing order and structure into the primeval universe, allowing the formation

of the fundamental particles, nuclei, and eventually protogalaxies and stars. Thus the claim is that the

ordered structures characteristic of the present epoch evolved by physical means, from the highly

disordered initial state very close to the origin of the Universe.

If this is so then the argument from low probability is entirely misconceived. We can all agree

that the Universe began in a (highly probable) chaotic state and evolved by purely natural law-like

means to its present highly ordered state. One admittedly must be very careful here because the

physics by which highly organised states can arise and persist in an environment where the overall

tendency is toward thermal equilibrium is just now being understood; nevertheless the logical gap in

the argument is clear.

6

So in the case of the ‘new’ design argument we have marshalled three criticisms:

1.

low probability events occur

2.

not all low probability events require special explanation

3.

at the origin of the Universe its state may not have been one of low probability, but a highly

chaotic random state, with a high prior probability.

The Cosmological Argument

The cosmological argument for the existence of God purports to establish that there is a necessary

being, a cause of all existent things. Even if it were successful it would still be a long way off

establishing that a being who is perfect, omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent exists. Indeed

whatever characteristics we may regard as characterising God in classical or neo-classical theism the

cosmological argument will, if successful, only give us a ‘creator’ or ‘cause’ of existence. What does

the argument really amount to? Well, it says just this:

(A)

There is existence

There is a cause of all existence (i.e. God)

Or in the more sophisticated version of the Kalam cosmological argument (so called because it

derives from the Islamic kalam form of dialectical argument):

Whatever begins to exist has a cause

The Universe began to exist

The Universe has a cause

(B)

And in the form you may be familiar with:

Premise (I)

Premise (II)

Premise (III)

Conclusion

Definition:

Everything has a cause

Nothing is its own cause

A chain of causes cannot be infinite

There must be a first cause

God is the first cause

(C )

First: this cannot be the right form of the argument because the conclusion, the existence of a first

cause, would seem to contradict the premise that nothing is its own cause. Let a be the first event, the

first cause which exists if the conclusion is true. Since, by premise (I), every event has a cause then

this event a, the first event, has a cause, call it b. But a is the first event, so providing subsequent

events don’t cause earlier events, b must be a. So since b causes a, and a is b, a causes itself. But

premise two says nothing causes itself. Notice that to get this conclusion we need an extra premise to

rule out backwards causation, (call this Premise (I*).)

So let us have another go to formulate the argument:

Premise (I)

Everything has a cause

Premise (I*) No event can cause an earlier event

Premise (II) Nothing is its own cause

Premise (III) A chain of causes cannot be infinite

Conclusion: there must be a first cause

Okay. So the idea now is to try to get Premises (I) (I*) and (II) to entail that the chain of causes

MUST be infinite. We will then use premise (III) to deny that conclusion. If we do that we must deny

one of the premises (I), (I*) (II) by logic (the rule of reductio ad absurdum). The premise we will

7

deny is PREMISE (II), and so derive that there is an event which is its own cause, and that will serve

as the first cause.

If we want to argue this way we will have to accept premise (III) as true. Is it? Certainly premises (I),

(I*) (II) do entail that the chain of causes is infinite, but why should we accept Premise (III)? In fact

we should not, it is simply not true.

Why can there not be an infinite descending chain of causal relations which has no first member?

(Aquinas seems to think this is unintelligible. He argues as follows: ‘Given therefore no stop in the

series of causes, and hence no first cause, there would be no intermediate causes either, and no last

effect, and this would be an open mistake. One is therefore forced to suppose some first cause, to

which everyone gives the name ‘God’”). But this argument has no validity. Consider the set of events

with no first member but a last member.

{.................an.........................a4, a3, a2 , a1 , ao}

no first

member

intermediate

causes

for every j (aj1 causes aj)

now

There is no logical contradiction in this supposition whatsoever. There would be perhaps if we said

that this set of events entailed that there was in the past an event infinitely distant from ao (now), but

of course just this entailment is incorrect, no such infinitely distant event need exist, every event

being finitely accessible from every other event. Every event in the above sequence is finitely

accessible from each and every event preceding it.

There is thus no logical contradiction whatsoever in the supposition that the Universe is

indefinitely old, in the sense that for any event in the Universe's history there are infinitely many

preceding events. Hence there is no logical necessity in assuming the truth of the second premise of

argument (B). Kant’s argument about incompleteness is beside the point.

Nevertheless, there is something very awkward in using terms like 'began' when we want to

talk about the Universe as a whole including time itself. Concepts like cause and beginning are

derived from our study of processes in time, ordinary physical processes, and then to make the

argument work we take these concepts completely out of context by attempting to apply them to the

Universe as a whole. Certainly we should be able to discuss questions about the origin of the

Universe but it does not seem to me to be even remotely appropriate to discuss the problem in terms

of concepts whose range of application presupposes that the ordinary background of time and space is

available. Precisely in this case it is not. Talk of beginnings and causes and creations presupposes a

background of space and time already present but the issue in question in the cosmological argument

is the origin and background of that very background itself. This is what is right about the

composition objection.

Perhaps an even more profound problem lies with the supposition of argument (A) (and in a

slightly different version in (B)) ‘Every event has a cause.’ The reason is straightforward. We now

have a very successful physical theory with an enormous amount of evidence in favour of it, the

quantum theory as standardly understood, which it turns out entails the existence of uncaused events

(so some things that begin to exist don't have causes). But if, as looks certain, one has to accept

uncaused events, the basic assumption that all events are caused must be given up. If that is so, why

then do we need to suppose that the Universe is caused?

8

A couple of final issues about this argument.

If everything has a cause, and the Universe is a thing, then the Universe has a cause. But this is to

presume that the Universe is a thing, an object or an event. Is it obvious that this is so? Finally as we

noticed the primum mobile must cause itself otherwise we would have an infinite regress. So God

must cause herself to be, this is the sense of “necessary existence” that is so important in the

conclusion.

It may look as if there is no hope for the cosmological argument, indeed I don't think there is

in its usual form. However, there is a formulation of it, due to Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, which

I think does pose a deep metaphysical problem. Leibniz's form of the argument was originally based

upon his famous principle of sufficient reason (everything that happens, happens for a reason, i.e.

there is some reason why one event happens rather than another). The claim then is:

Is there a reason why there should be Nature rather than nothing?

This reason is, of course, the necessary being God. Let us now take the argument out of its

Leibnizean form and ask simply: ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’ This is not a

scientific question but a metaphysical one, and it's this which is the interesting core of the

cosmological argument.

Ultimate Explanations

Progress in scientific knowledge has revealed that the vast complexity and interconnectedness of

Nature is the result of the interaction of natural processes obeying law-like regularities. One need

think only of the laws of evolution (e.g. of random variation, inheritance and natural selection) to see

how the integrated complex of a primeval rain forest may be brought about; or think of the laws of

molecular physics and chemistry to see how beautiful, highly structured icebergs may be created by

the shattering and shearing forces within ice under pressure, say, at the edge of the Antarctic

continent.

The discovery of the law-like behaviour of matter and radiation in the Universe, is the

starting point of the form of the design argument which appeals to ultimate explanations. The

argument runs as follows: the system of scientific laws, rather like an engineer's blueprint, exhibits

the design in Nature. For in the end there must be some basic or ultimate laws, and they will be

inexplicable by scientific means precisely because they are ultimate. At that point, the explanation

can only be a theological one, namely, that precisely these laws exhibit God's design. The argument

has been put particularly clearly by Richard Swinburne in his book The Existence of God, from which

the following quotation is taken (pp. 138-9):

“The universe is characterised by vast, all-pervasive temporal order, the conformity of nature

to formula, recorded in the scientific laws formulated by men. Now this phenomenon, like the

very existence of the world, is clearly something ‘too big’ to be explained by science. If there

is an explanation of the world's order it cannot be a scientific one, and this follows from the

nature of scientific explanation. For, in scientific explanation we explain particular phenomena

as brought about by prior phenomena in accord with scientific laws; or we explain the

operation of scientific laws in terms of more general scientific laws (and perhaps also

particular phenomena). Thus we explain the operation of Kepler's laws in terms of the

operation of Newton's laws (given the masses, initial velocities, and distances apart of the

sun and planets); and we explain the operation of Newton's laws in terms of the operation of

Einstein's field equation for space relatively empty of matter. Science thus explains particular

phenomena and low-level laws in terms partly of high-level laws. But from the nature of

science it cannot explain the highest-level laws of all; for they are that by which it explains all

other phenomena.”

There are two difficulties with this argument. First, granted the existence of ultimate laws of nature,

why are those ultimate laws thought to be in need of explanation? Secondly, why should we think that

9

there must be ultimate laws of nature at all? Let us start with the first problem: why are ultimate laws

thought to be in need of explanation? If the laws are ultimate then clearly, by definition, there can't be

a scientific explanation of them. Why then should we require that there be any explanation of them? It

begs the question to say that these laws must have an explanation, once we have agreed that they are

ultimate. We can't hope to establish God's existence by insisting that they do have an explanation,

since it is always possible to assert that they simply hold as a matter of fact, a further argument would

be needed to show that that possibility was ruled out. Of course, if we already had a metaphysically

satisfactory proof of God's existence then we could appeal to that hypothesis here. But the argument

cannot, on its own, establish God's existence.

It might be thought that given the existence of ultimate laws the most probable hypothesis

was the existence of a God whose plan for the Universe consisted of those laws. But the hypothesis

of a complex ordered Universe and an equally complex, sophisticated designer cannot have a

probability greater than the probability of the existence of a complex and ordered Universe alone. So

even if we accept the existence of ultimate laws, we still do not have an argument for God's existence.

Let us now turn to the second difficulty with the argument concerning the existence of

ultimate explanations. When we explain in Science, we make appeal to law-like statements. For

example, if we are asked to explain the phenomenon of the tides we appeal to Newton's gravitational

law and to certain facts about the relative motion of the sun and the moon with respect to our planet.

We may then be asked for an explanation of why Newton's law holds. We might explain this by

appeal to a more general law or theory. Indeed we would show Newton's theory to be a limiting case

of the General Theory of Relativity. Now, of course, we may be asked for an explanation of why the

General Theory holds, and so on and so on. Since it is always possible to pose the problem: why does

such and such a law hold, we can generate an unending sequence of explanatory problems, whatever

stage of science has been reached we can always ask why the basic laws accepted at that stage hold,

and so generate a new scientific problem.

It is sometimes claimed that the list of answers to these questions (i.e. the search for laws of

ever increasing generality) must end somewhere, on pain of never explaining anything. But this is not

true. We certainly have explained, for example, tidal motion, if the correct account of tidal motion

follows from a true law of nature given certain initial conditions. Of course, one can have all sorts of

grounds for the truth of a given law-like statement quite independently of its deducibility from some

higher level law; it may, for example, have survived many experimental tests. So the supposed

‘infinite regress’ of explanation no more undermines the existence of explanations than does the

‘infinite regress’ of proofs undermine the existence of proofs in mathematics. Since proofs always

rely on some unproved set of basic postulates or axioms, it is always possible (though certainly not

always appropriate or useful) to ask for a proof of the basic postulates in some wider mathematical

theory.

All this shows is that there can be no argument from Science that there must be ultimate laws.

It does not show that there are no ultimate laws. Nevertheless, it is clear that the idea of ultimate

explanations is antithetical to Science and its practice. Science is an unlimited enterprise, in that

explanatory questions will always remain to be asked (and answered). If we want to use ultimate

explanations to argue for God's existence, and have no argument to show that there must be ultimate

explanations, we shall need an argument to show that ultimate explanations actually exist. So before

we can use them to show God's existence, we will need a new design argument that there are such

things. It seems, then, that there is an unbreakable circle of argument here.