Toxic Ten - PennEnvironment

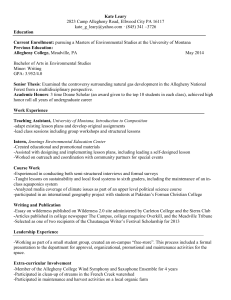

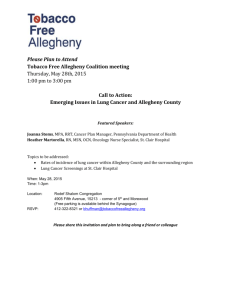

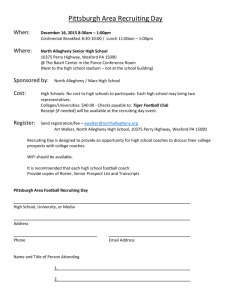

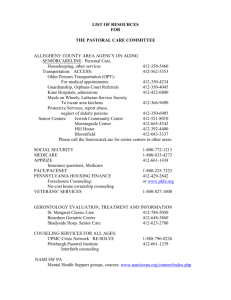

advertisement