How women pay the price for population control

advertisement

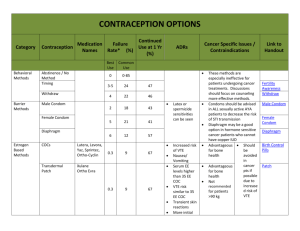

Women’s health Population Control How women pay the price for population control Despite the serious toll it takes on women’s health, female sterilisation remains the most prevalent form of contraception in India. ruhi kandhari reports W hile memories of the 21 months of Emergency in 1975-77, imposed by the then prime minister Indira Gandhi, survives even today in the minds of Indian men as the fear of forced sterilisation, the country’s population control policies have shifted over the years since then to target the politically less powerful and vulnerable poor women. Almost the entire burden of what is euphemistically called “family planning” is today borne by women. And it has taken a toll on the health of large sections of women in the country. In fact, the mainstay of our population control strategy comprises two methods targeted at women — tubectomy (female sterilisation surgery) and insertion of an intrauterine device (iud) also known as Copper-T. Neither method is known to be suitable for all women. Yet, in the rush to meet targets, these methods are widely promoted and their adverse effects on women ignored. The public health infrastructure is not geared to manage contraception, the staff is not trained in counselling women or seek their informed consent, and pain is considered an acceptable side-effect. According to the latest National Family Health Survey, conducted in 2005-06, a third of the women in the reproductive age group have undergone surgery for sterilisation and thousands have been inserted with iuds, with or without their consent, at some point in their lives. After months of suffering pain, many women have to visit private clinics to get the 00 tehelka 11 october 2014 iuds removed as the government hospitals largely refuse to do so. While the World Contraception Day was observed on 26 September, the time is apt to take a hard look at India’s population control policies from the perspective of the women who are forced to suffer its consequences. Take the case of 30-year-old Rajkumari from New Delhi, who underwent tubectomy five years ago. In five years of marriage, she had three children, followed by three abortions. A social health worker appointed by the state government had convinced her that this was the only way to avoid pregnancy, while her husband was never counselled to use contraception. Since the surgery, Rajkumari has not been able to sleep peacefully on most nights. She often suffers from recurring headaches, hot flashes, night sweats and stabbing pain in her abdomen. In the month following her surgery, she visited the government hospital several times, but the doctors only prescribed her medicines to control the symptoms. “The medicines only offered temporary relief. My life has been a curse for the past five years with constant suffering,” she says. Her neighbour, 23-year-old Pushpa, also narrates a similar tale of pain. The nurse at a public health facility inserted her with an iud after she delivered her first child. Her consent was not sought. The procedure was done after getting the consent form signed by her husband, a daily wage labourer who had studied up • Post-operative hell Sterilisation camps for women are often conducted without proper medical infrastructure like operation theatres, in a hurry to meet targets photo: down To earth 11 october 2014 tehelka 00 Women’s health to Class V. He wasn’t explained what an iud is and what the form was for. Pushpa was dizzy when she returned home. She bled profusely, became pale over time and stayed bed-ridden. Her periods lasted up to two weeks sometimes. She lost her appetite, became weak and was unable to feed her baby on most days. When she went back to the hospital, she was prescribed antibiotics and painkillers. But she continued to bleed and suffered from pain in her abdomen. It took her three months to save enough money to get the iud removed at a private clinic. The common known side-effects of iuds are nausea, changes in menstrual bleeding and severe cramps. Sterilisation, on the other hand, is a risky surgery that may lead to internal infection or bleeding, injury to internal organs and even death. There are thousands of women like Rajkumari and Pushpa who have suffered the terrible side-effects of tubectomy and iuds. Stuck on a wall in the lobby of the office of New Delhi-based ngo Centre for Health and Social Justice (chsj) is a clipping of a June 2013 article by the Bloomberg news service headlined ‘Pushing Indian Women toward Sterilisation’. It tells the story of Sumati Devi, who underwent sterilisation on an “operating table with bloody sheets”. The operation was done with a rusted scalpel and she was neither counselled nor asked for her consent. Instead, she was given some cash as an “incentive”. The article threw light on how 10 times more women than men undergo sterilisation surgeries in filthy “sterilisation camps”, even though female sterili- Population Control Contraception prevalence in India versus rest of the world India ranks the highest in risky contraception and the lowest in safe contraception Female Male sterilisation sterilisation World India Africa China Europe North America sation involves a more complicated operation than male vasectomy. Another clipping from February 2012 headlined ‘Pregnant woman bleeds to death after sterilisation’ (The Times of India) told the story of a 35-year-old pregnant woman who bled to death in Balaghat district of Madhya Pradesh while the doctors were trying to sterilise her. She had been pregnant with twins — both girls — for 12 weeks when the operation was conducted. She died a few hours after she began bleeding on the operation table because the doctors did not follow the basic protocol of medically screening Disadvantages and side-effects of various contraceptive methods tehelka 11 october 2014 2.8% 1% 0% 6.9% 2.6% 11% Condom 8.8% 3.1% 7.8% Not known 20.3% 18.6% 6.1% 1.2% 1.7% 4.4% 14.3% 12.5% (Source: UN World Contraceptive Report 2009) The downside of contraception 00 20% 37% 1.5% 33% 3.8% 21% Pill women before the sterilisation operation. There was also a clipping of a January 2012 story titled ‘Barrack-room surgery in Bihar’s backwaters’ about a sterilisation camp conducted by an ngo in a hamlet in Araria district without any operation theatre, where 61 tubectomy surgeries were carried out at a breakneck speed using expired medicines. Another clipping on display was of a March 2012 article titled ‘Freebies lengthen sterilisation queues’ (The Deccan Herald) talked of how a district administration won a Tata Nano car for meeting sterilisation targets. Giving lpg connec- Oral Contraceptive Pill Nausea, mild headaches, tender breasts, spotting between periods, irregular bleeding, moodiness, vomiting within two hours of taking a pill, severe diarrhoea and vomiting for more than 24 hours Copper-bearing IUDs Menstrual changes in early months, longer and heavy menstrual periods, bleeding or spotting between periods, more cramps or pain during period. Uncommon sideeffects include severe cramps and pain beyond first threefive days of insertion, heavy menstrual bleeding or bleeding between periods, possibly contributing to anaemia and possibility of perforation if not inserted properly. It does tions to every family from which a woman underwent tubectomy, the administration had got over 2,000 tubectomy surgeries carried out in just three days. According to the most recent data collected in 2012-13 under the District Level Household and Facility Survey, state governments increasingly prefer female sterilisation as a mode of family planning even though it is one of the most risky contraception methods. In Andhra Pradesh, for example, 63 percent women in the fertile age range had been operated upon in 2012-13 as compared to 60 percent in 2007-08. During the same period, the number of men who underwent sterilisation dropped from 4 to 2 percent. Similarly, in Maharashtra, the percentage of women who underwent sterilisation increased from 52 to 54 percent, while the corresponding figure for men dropped from 3 to 1 percent. In Haryana and Punjab, one-third of the women in the reproductive age range have been sterilised. Although tubectomies involve a serious chance of surgical infections and post-operative complications, state governments continue to promote “camps” where these are conducted on thousands of women without any proper health infrastructure and in unsanitary conditions, in a hurry to meet targets. This is despite the fact that vasectomy for men is a relatively non-invasive procedure with little risk of surgical infections and the men undergoing the procedure are usually fit enough to walk only minutes later. “The government’s focus is only on terminal methods targeted at women. Men are hardly involved in the family planning programme. They need to be in- not protect against sexually transmitted diseases (stds) including hiv/aids. Medical procedure, including pelvic examination, is needed to insert the iud. Occasionally, a woman faints during the insertion procedure. A trained healthcare provider must remove the iud. The iud may come out of the uterus possibly without the woman photo: vijay pandey • Unending curse Rajkumari, 30, has had recurring health problems since undergoing tubectomy 5 years ago volved, not as targets for non-scalpel vasectomy but as partners within a genderequality paradigm,” says Dr Abhijeet Das, director of chsj and an assistant professor at the Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, USA. For the past two decades, Das has been observing persuasive population control programmes, advising the government and is also part of various national and international networks, including the National Alliance on Maternal Health and Human Rights, Healthwatch Forum and MenEngage, a global alliance on men and gender equality. knowing about it (more common when the iud is inserted soon after childbirth) Vasectomy Uncomfortable for two or three days, pain in scrotum, swelling and bruising and brief feeling of faintness after the procedure. Rare complications of surgery include bleeding or infection at the incision site or inside The 2012-13 survey also shows indicators that define the “quality of family planning services” remain abysmally low. Most women are unaware of other means of contraception and the known side-effects of sterilisation. Even when they are counselled, the counselling is manipulative as the staff has already decided which contraceptive method a woman needs. In Maharashtra, only 17 percent of the women were told about the side-effects, while the figure was 14 percent in Punjab and 11 percent in Andhra Pradesh and Haryana. According to the District Level Household & Facility Survey 2007-08, 40 per- the incision, blood clots in the scrotum. No protection against stds, including hiv/ aids Tubectomy Uncommon complications include infection or bleeding at the incision, internal infection or bleeding, injury to internal organs and anaesthesia risk. No protection against stds Male Condom Latex condoms may cause itching for a few people who are allergic to latex. Also, some people may be allergic to the lubricant on some brands of condoms. Small possibility that condom might slip off or break during sexual intercourse (Source: Government reference manual) 11 october 2014 tehelka 00 Women’s health Population Control cent of the women who underwent tubectomy in public health facilities across India were illiterate, indicating that tubectomy was not the “chosen” form of contraception. Despite the problems associated with tubectomies, state governments continue to set targets for sterilisation surgeries. The reply to an rti query showed that around 1,000 women were targeted for tubectomy in just west Delhi over the months of January, February and March this year. T he two extremes of the debate on how to stabilise the population are represented by the coercive sterilisation drive associated with Indira Gandhi’s son Sanjay Gandhi during the Emergency, on the one hand, and senior Congress politician Karan Singh’s statement at the 1974 World Population Conference in Bucharest, Romania, that “development is the best contraceptive”, on the other. For a long time, the dominant thinking globally was in favour of coercive policies. Internationally, this debate came to rest at the International Conference on Population and Development 1994 (icpd 94) in Cairo, Egypt. At icpd 94, civil society activists from around the world shared experiences of coercive population policies and convinced 179 national governments to see “population” as people, not a number. Economists like Amartya Sen had also proved by then that improvements in women’s education and healthcare automatically result in smaller families without any need for authoritative population control policies. icpd 94 brought about a “paradigm shift”. The governments agreed to abide by reproductive rights and honour gender equality while providing universal access to family planning, sexual and reproductive health services. The Indian government, too, grudgingly committed to place individuals at the centre of development. However, the state governments in India by and large do not follow this principle in practice and it is not uncommon for politicians, bureaucrats, judges and the educated, urban middle class to blame India’s large population for nearly all the problems plaguing the country and favour force over cooperation. 00 tehelka 11 october 2014 • No consent No one sought the permission of Pushpa, 23, before inserting her with an IUD Until icpd 94, population was considered a dirty word — a dangerous “bomb” that would explode if not controlled. In the early 1950s, more babies were surviving in the newly-independent countries and fewer children were being born in the richer countries, leading to a fear of “overpopulation” in the Global South. This led to the formation in 1952 of two ngos — the Population Council and the International Planned Parenthood Federation (ippf) — in New York and Bombay, respectively. They were set up with the purpose of influencing the US government to orient the US Agency for International Development (usaid) towards population control in the Third World, alerting Americans to the danger of population “explosion” and raising funds for international birth control programmes. An advertisement for a joint campaign by the two ngos read: “A world of mass starvation in underdeveloped countries will be a world of chaos, riots and war. And a perfect breeding ground for communism… Our own national interests demand that we go all out to help the underdeveloped countries control their populations.” The political agenda was reinforced and validated by Stanford University Professor Paul R Ehrlich, who authored The photo: vijay pandey Population Bomb in 1968. He emphasised birth control at any cost with the use of contraceptives, mass sterilisation and pre-natal sex determination (so that parents can design the family sex composition). The US government was soon convinced. In 1974, National Security Study Memorandum 200 of the National Security Council asserted that population growth in poor countries posed a problem for the security of the US. That is how the US and other industrialised countries, which had achieved lower birth rates due to improvements in education, healthcare and incomes, without any coercive population control policies, became the biggest proponents of the latter. India could not remain unaffected by the discourse. In 1970, JRD Tata formed the Population Foundation of India with money from the Ford Foundation for population control advocacy in India. While the country’s population initially focussed on vasectomy of men and stayed clear of female sterilisation, considering the risk of infection, the tide had turned by the 1980s. The infamous coercive male sterilisation drives of the Emergency period gave way to the setting of targets for female sterilisation, which continues to dominate the population control policy. In 1992, a study by Dr Rani Bang and Dr Abhay Bang demonstrated that women had more faith in indigenous methods of contraception than the modern ones because they commonly associated the latter with adverse effects such as backache, abdominal pain, weakness and irregular or excessive menstruation. Women also found that healthcare professionals were often insensitive to these complaints and regarded them as minor and insignificant side-effects that should be ignored. I CPD 94 was the culmination of the coming together of academics, activists and the medical community in efforts to propose an alternative perspective on population control policies. They showed how a policy of targets, incentives and disincentives under the National Family Planning Programme had made women mute recipients suffering quietly. Among the participants at icpd 94 was an ias officer, AR Nanda, who was then the secretary at the Union Ministry of Health. After he returned from Cairo, he took up the mantle to reorient the population policy. The second half of the 1990s saw a new target-free approach, which focussed on combining contraception needs with providing reproductive and child health. Nanda also drafted the landmark National Population Policy (npp) 2000, which stressed on improvements in human development, gender equality and reproductive health to stabilise population growth. “In 1999, when I proposed the npp, a few mps supported the two pillars of the policy — informed choice and informed consent — but it was largely criticised in Parliament,” says Nanda, who has since retired from the government, but continues to advise the National Coalition Against Two-Child Norm, an advocacy group of ngos, academics and activists concerned with promoting policies that empower people to exercise their reproductive rights and choice. State governments have often promoted population control methods that go against the spirit of NPP 2000 The npp 2000 begins with a statement that “the overriding objective of economic and social development is to improve (the) quality of life that people lead, to enhance their well-being and to provide them with opportunities and choices to become productive assets in society”. The policy recommended the empowerment of women through enhanced access to education, employment opportunities and quality healthcare. The policy, however, failed to influence a large section of politicians who continued to see population as a problem. In May 2000, when India’s population crossed the one-billion mark, the then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee said: “This is a serious matter that is both cause for concern and introspection — concern over the impact that a runaway population growth is bound to have on the nation’s economic, natural and other resources; introspection over where we went wrong and how we can stabilise our population… If the present growth rate of our population remains unchecked, India will become the world’s most populous country by the middle of this century, with people clamouring for a share of shrinking natural resources.” Opposition to npp 2000 continued even after it was adopted. Population being a subject on the Concurrent List, the state governments are not obliged to follow anything that the Centre prescribes on population control. They have their own policies that in most cases go against npp 2000. For instance, Uttar Pradesh introduced contraceptives such as injectables and implants, which are proven to be unsafe for women; Rajasthan promoted a lottery scheme for those who opt for sterilisation; and Bihar contracted out tubectomy surgeries to private operators and ngos. “The language used in talking about population stabilisation changed after icpd 94 but the mindset remained more or less the same,” says Nanda. “Even at the national level, male responsibility and gender equity were largely ignored. The state governments favour setting of targets and promoting terminal methods because the results are easy to measure.” Clearly, despite all the talk of empowering women, their reproductive autonomy — the right to choose whether to have children or not and the freedom to choose the methods of fertility management based on access to proper information — has been largely ignored in the policies and practices promoted by various governments in India. Unfortunately, India has seen a reduced prevalence of condom use with women remaining unequal targets of the family planning burden. As the dominant, irreversible methods of population control take a toll on women’s health, there is indeed a need for reorienting it towards the promotion of temporary and reversible methods such as condoms, which also provide a barrier against sexually transmitted diseases. letters@tehelka.com 11 october 2014 tehelka 00