Changing the Culture of Alcohol in Nova Scotia: An Alcohol Strategy

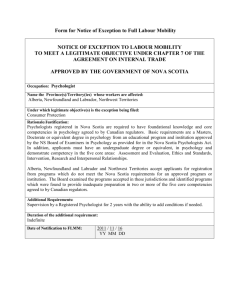

advertisement