MASONIC CIPHERS The word CIPHER has a variant spelling of

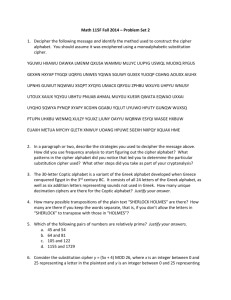

advertisement

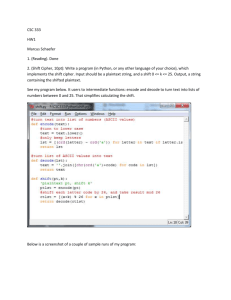

MASONIC CIPHERS The word CIPHER has a variant spelling of CYPHER. It is derived from the Arabic cifr, meaning empty or zero. It is a character of any kind used in writing or printing; a code or alphabet used to carry on secret correspondence designed to be intelligible only to the person concerned, the one who holds the key. There are two other usages for the word CIPHER, firstly to work by means of arithmetic; and secondly, a sound from a defective organ pipe. These may be interesting but are not the purpose of our talk. Civilian, political and military leaders have always had a need to communicate with their own people at a distance. One need was speed of communication but another was secrecy, because they did not want their thoughts, their intentions and plans to be known to others if their courier was captured. One ruler had his courtier’s head shaved and a message tattooed onto it. When the hair had regrown, the courtier was sent to deliver the message. Obviously speed was not a consideration with this message except that the hair grew back reasonably quickly. A Spartan ruler once had a message sent to him scratched onto a wooden tablet that was then covered with wax. To all intents and purposes it looked like an ordinary wax tablet that had not yet been used because the message was under the wax and not scratched into it. The secret message was revealed when the tablet was held near heat and the wax melted away. Naval vessels communicated with each other by means of flags that individually and in combinations, formed words and messages. The meanings were varied from time to time so that the enemy could not understand the messages being conveyed so openly, if code-books had been captured. If capture was imminent, the first responsibility of a naval commander was to destroy the coded meanings for his flags. In World War II, the Germans used a device called ENIGMA to convert military messages into a form unintelligible to the allies when they intercepted them. It took thousands of people trying manually to break the codes for a little success and later the British developed their own electronic methods to decipher and which might, justifiably be credited with giving them an edge by which they won the war. Many years ago I had the pleasure of hearing the late R.W. Bro. John Danks, Grand Lecturer as they were then called, give a talk on the Masonic cipher, with particular reference to that part which appeared on the third degree tracing board. Since that time I have not heard the subject mentioned and determined to do the research so the subject could be presented to a new generation of Masons. The seven degrees in the Mysteries of the Kabbalists corresponded to the seven chief “Internal Ceremonies”, the first of which was quite elementary and might properly be called the abc of their science. All that was done in it was to entrust the candidate with the key to certain Anagrammic Alphabets by which they learnt to both hide and decipher their genuine secrets. The Kabbalists possessed many expedients for ascertaining the inner meaning of the Law of Moses and these arts were supposed to be of high practical value. They claimed that these gave them access to secrets embodied in the Law. In later times, Freemasons, being unable to properly handle these Anagrammic Alphabets, had to give them up. The Freemasons invented their own alphabet of squares and angles, which has come to be regarded as the Masonic system of writing; it was not exactly a substitute for the Anagrammic Alphabets but it was meant to replace them. Still it served its purpose by being employed as a secret code. It cannot be said to have been a success but remnants have been handed down to our time in the tracing boards. There are now very few Masons who know how to employ it, or who could decipher even the brief specimen that stands boldly at the top of one of those pictorial designs. A French writer of the 18th century informs us that a square, its portions and the different positions into which they may be placed, with the aid of a dot, will form an alphabet of 24 letters. This is the secret alphabet of freemasonry. Oliver gives us two versions in English having 26 characters, and with them, the original and improved continental type plus the American types of the Masonic alphabet. We cannot ascertain who was the original author of the ingenious scheme, but the important point to remember is that it was a substitution for the Hebrew System, introduced after the Hebrew Alphabet had ceased to be used by Freemasons. The first challenge was to re-create the list of characters (or shapes) that represented the 26 letters of the English alphabet. That was achieved relatively easily, but complicated by finding many variations on a theme! This was not what I expected but I have replicated them and will hand them out later for your interest and you can peruse them at your leisure. Just to digress, I will mention that when I had the first set of characters representing the alphabet, I sent notes in code to my grandchildren using the cipher and they think I am real cool because we can send and receive secret messages that no one else can read, unless they are given the key. The second challenge was to find out who had created this plethora of Masonic Ciphers, when they were created, and for what purpose. One answer I was given was “to use on 3rd degree tracing boards”, but this was so obviously an incomplete view that it can be immediately discarded. Certainly a few characters are illustrated on the board as I will shortly demonstrate, but there had to be a more far-reaching answer than that. Any E.A.F. or F.C.F. present can hear the talk and see all but the 3rd board. Bernard Jones mentions that “certain of the American Grand Lodges closely supervised the ritual practiced in the Lodges under their jurisdiction; one of them used to issue a copy of the Craft ritual in cipher to each Lodge Master, who duly passed it on to his successor. American chapters work to an approved ritual issued to them in cipher.” He further mentions that various toasts used at Royal Arch meetings were listed in Browne’s ritual written in cipher in 1798. The Chapter of Friendship, Portsmouth into which the great Thomas Dunckerly was accepted, kept their minutebook in cipher, as did some other Masonic bodies in the 18th century. Would you like to receive your ritual book in the form of a cipher? I think not, as you would have to translate into a written version that you could study in order to render it correctly, which defeats the purpose of enciphering it in the first place. Not only that but every holder of the enciphered ritual would have to hold the key, either that or remember the entire ceremonials. There is another reference made by Bernard Jones and that was to the proposed creation of the position of Masonic Professor as follows, “In the course of the report ultimately made by the Lodge of Promulgation to the grand Master a suggestion was made for the institution of the Office or Degree of Masonic Professor of the Art and Mystery of Speculative Masonry, to be conferred by Diploma on some skilled craftsman of distinguished requirements and general fitness.” The recommendation went on to outline what this Pandect or compendium should cover and that it should be able conclusively to decide any issues and effectually govern the practice of Freemasonry ever after. Finally this Pandect should be written in Masonic cipher. From all of the above references made by Bernard Jones, we can deduce that Masonic ciphers were in vogue in the 18th century, and that they were used in Craft Masonry as well as Mark and Royal Arch Masonry. Further, the inference is that quite long documents were envisaged as being in cipher, e.g. Lodge rituals, Lodge minutes and the proposed Pandect, which would seem to have been equivalent to our Book of Constitution and the Codifications of the Decisions of the Ritual Committee, combined. Incidentally that proposed Pandect never eventuated. My personal observations are that having used one form of the cipher to send notes to, and to receive notes from, my grandchildren, it is exceedingly tedious to transform a message into cipher and also for the recipient to decode it back to normal text. I can only assume that our brethren of the past ages had far more time on their hands than we do. I cannot imagine any modern Lodge Secretary first recording the minutes of a meeting in longhand, then encoding them in cipher into the minute book, only to read them out in Lodge at the next meeting for confirmation, from his original longhand notes. Perhaps in some places and at some times there may have been a need to leave no written records that could be used against the members of the Craft, from some persecuting group or another, but other than that it is hard for us to imagine the need to take such steps as ciphering to preserve secrecy. Freemasonry has been described as being esoteric in nature. Esoteric means restricted to or intended for an enlightened or initiated minority, especially because of abstruseness or obscurity. In this context, reducing rituals, minutes and constitutions into cipher that was unintelligible to anyone else would certainly make Freemasonry esoteric. However over the centuries there have now been so many books and articles disclosing the “true secrets of Freemasonry”, and even exposes on television and film, that the need for such time consuming effort as ciphering has been removed for ever, except perhaps as a curiosity, or as a reminder of things that once were. I made enquiries to see if I could lay my hands on some original enciphered document, or even a photocopy of one to show you, but was unsuccessful, which was quite disappointing. I wanted to share with you any official reason or explanation for the subject of our talk tonight. Then I accidentally found two documents recreated in a book in our Grand Lodge library. The book is entitled Ritual of Freemasonry and all I had to do now was to decode them into a readable form, but more of that later. What I can tell you, however, is that in the final year of his reign, King Henry VIII proclaimed and enforced the Act of 1547 which dis-endowed all religious fraternities. Henry’s son and successor, Edward VI, confiscated any remaining guild funds. The available records indicate that, of all the fraternities in England, the stonemasons probably fared the worst under the Act of 1547. Those fragmented guilds that survived the Reformation became Livery Companies. One known as the The Worshipful Company of Free Masons of The City of London prior to the Act of 1547, or more familiarly as The Fellowship of Masons, was kept alive through the Reformation, carefully hidden from official eyes and jealously guarding its medieval craft doctrines and secrets. Although the Company’s books and records prior to 1620 have been “lost”, the letter-books and other records of the City of London confirm the Company’s continuity through to 1655, when it changed its title to The Company of Masons. Now some of you would ask why should the King’s decree so adversely affect Freemasons as we are not a religion. This is, and was, true, but the operative masons were most certainly not irreligious they usually being commissioned by the church for so many of their grander buildings. What is true is that the operatives observed all the religious days and even conducted their own religious plays on certain occasions. Some learned scholars even believe that much of the ritual of our ceremonies is derived from the concept of religious plays performed by the operative masons in their lodge rooms on holy days. Research into the entrance of various English notables, men of good repute who were not operative Masons, into speculative Lodges is frustrating because nothing is known of the dates and places of their admission into Freemasonry. This lack of information is common in the minutes of early English speculative Lodges and is one of the reasons for the uncertainty regarding their origins and their activities but it also means that some of the Lodges might have been in existence longer than is generally assumed. This lack of records was probably not through laxity, but to avoid persecution during the religious and political disruptions that plagued England after the Reformation. Let us summarise, some two hundred or more years ago it was perceived that there were dangers to our fraternity that necessitated certain documents to be encoded into a form that rendered them illegible to non-masons. I am not sure in which country this practice originated however, England, France and the USA saw fit to employ them. In France, as recently as 1917 a form of concealment was to write certain words backwards. The practice of writing backwards on 3rd degree tracing boards commenced about 1825, and is still evident today. Now let us look at the practicality of creating the key to a cipher and looking at various keys used at one time or another by different Masonic organizations. Finally we will look at the documents I found recorded in the book previously mentioned, and the translations. Why reverse the characters before decoding them? The answer is based on the words that Masons have heard so often in another section of ritual, quoting “ you will observe that we did not give the letters in their consecutive order. This was done to involve the word in greater mystery.” Finally there is a further reference perhaps indirect depending upon your point of view, in the great and solemn obligation of an EAF when in his obligation “whereby or whereon any letter, character or figure, may become legible or intelligible to anyone in the world.” I feel that these words, “letter, character or figure” have a direct reference to the use of this craft cipher or code. If you are reading this talk it means that you are not present to see the presentation of the various ciphers, or to see how they were compiled. If you are interested I can be contacted through the GL Library and we will see what can be done to share the interesting bits of the story with you. V W Bro Robert Taylor