When a Few Bad “Mongols” Spoil the Bunch, Should the Government

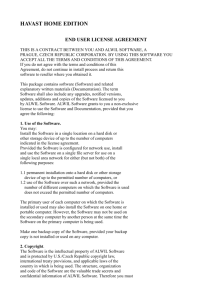

advertisement