- D-Scholarship@Pitt

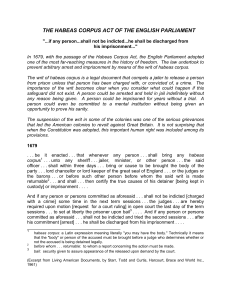

advertisement