Page 1 CONSTITUTIONAL LAW I: SEPARATION OF POWERS

advertisement

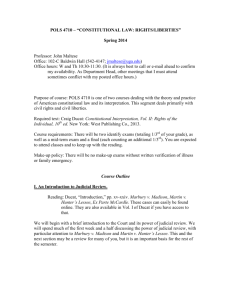

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW I: SEPARATION OF POWERS/FEDERALISM POLS 6440 – Fall 2012 John A.Maltese Baldwin Hall 542-2559 (office) jmaltese@uga.edu Office Hours: by appointment Course Description: POLS 6440 is one of two graduate seminars on the theory and practice of American constitutional interpretation. The primary emphasis will be on case law. This segment deals with separation of powers and federalism. Texts available for Purchase: Craig R. Ducat, Constitutional Interpretation, 10th ed. (Thomson/West, 2013). Course Requirements: There will be a 15-20 page paper (topic to be assigned)(35%), two identify quizzes (15% each), and a final exam (35%). Syllabus format: “Reading” is the material that must be read each week before class. “Cases” are usually included in the readings, but I have listed the most important cases that we will be discussing. Also included are some recent cases (accessible on-line). For the quizzes and exam, you should know the legal questions raised by each of these cases and be able to identify all of the opinions in the cases (majority, concurring, dissenting) -how each opinion answered those questions and why. Thus, it is important to read the cases carefully when they are assigned and to brief them. This is a basic list of cases that you should be familiar with if you take comps in the field of “Law, Courts, and Judicial Process.” “Additional” is a supplemental reading list that you should skim. I may assign some students to read some of these in more detail and to provide an outline to the rest of the class. Although this list is certainly not exhaustive, it consists of a basic core of readings that anyone taking comps in the field should be familiar with. I. The DISTRIBUTION OF POWERS WITHIN THE NATIONAL GOVERNMENT A. Introduction: “Constitutionalism” and the Doctrine of Judicial Review. Reading: Ducat, chapter 1 (section a); William Van Alstyne, “A Critical Guide to Marbury v. Madison,” 1969 Duke Law Journal 1 (1969) (handout). Cases: Dr. Bonham’s Case Hylton v. U.S. Marbury v. Madison Judge Gibson’s dissent in Eakin v. Raub Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee Cohens v. Virginia Additional: Much has been written about the framing of the Constitution. It is worth reviewing the Articles of Confederation, the Virginia Plan, and the New Jersey Plan, as well as the Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers. For information on the Anti-Federalists, see: Saul Cornell, The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788-1828 (North Carolina, 1999). Herbert J. Storing, ed., The Complete Anti-Federalist (Chicago, 1981). For a classic overview of the framing of the Constitution, see: Max Farrand, The Framing of the Constitution of the United States (Yale, 1913). Farrand also edited the most systematic collection of notes from the convention: Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (Yale, 1911). There is a wealth of material on the Court’s power of judicial review. For some competing views about the legitimacy of judicial review itself, see: Learned Hand, The Bill of Rights (Harvard, 1958), pp. 1-30. Herbert Wechsler, “Toward Neutral Principles of Constitutional Law,” 73 Harvard Law Review (1959), 1. Kermit L. Hall, ed., Judicial Review in American History: Major Historical Interpretations (Garland, 1987). Books on Marbury v. Madison include: Robert Lowry Clinton, Marbury v. Madison and Judicial Review (Kansas, 1989). William Edward Nelson, Marbury v. Madison: The Origins and Legacy of Judicial Review (Kansas, 2000). Mark A. Graber and Michael Perhac, eds., Marbury v. Madison: Documents and Commentary (CQ, 2002). Paul W. Kahn, Marbury v. Madison and the Construction of America (Yale, 1997). For an overview of the major arguments concerning judicial review, see: Leonard Levy, ed., Judicial Review and the Supreme Court (Harper, 1967). This includes classic essays by James Bradley Thayer, Henry Steele Commager, Eugene V. Rostow, Robert Dahl, and others. B. Limits on Judicial Power Reading: Ducat, chapter 1 (section b); Gerald Gunther, “Congressional Power to Curtail Federal Court Jurisdiction: An Opinionated Guide to the Ongoing Debate,” 36 Stanford Law Review 895 (1984) (available online through UGA’s Galileo at the Lexis/Nexis site). Cases: Muskrat v. U.S. Padilla v. Hanft Sosna v. Iowa Doe v. Bush Allen v. Wright DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno Frothingham v. Mellon Flast v. Cohen Baker v. Carr Bush v. Gore Additional: The Court’s “gatekeeping rules” (or “threshold requirements” often seem tortuous and contradictory. For a good overview, see: Louis Fisher, Constitutional Dialogues (Princeton, 1988), chapter 3. See also: Henry Monaghan, “Constitutional Adjudication: The Who and When,” 82 Yale L.J. 1363 (1973). Antonin Scalia, “The Doctrine of Standing as an Essential Element of the Separation of Powers,” 17 Suffolk U.L.Rev. 881 (1983). Henkin, “Is There a ‘Political Question’ Doctrine?” 85 Yale L.J. 597 (1976). Philippa Strum, The Supreme Court and “Political Questions” (Alabama, 1974). There has been great debate over the jurisdiction-stripping power of Congress. For a close examination of the major case on this issue, see: William Van Alstyne, “A Critical Guide to Ex Parte McCardle,” 15 Ariz.L.Rev. 229 (1973). For discussions of Congress’s jurisdiction-stripping powers, see Henry M. Hart, Jr., “The Power of Congress to Limit the Jurisdiction of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic,” 66 Harv.L.Rev. 1362 (1953). Herbert Wechsler, “The Courts and the Constitution,” 65 Columbia L.Rev. (1965). For a discussion of Congress’s efforts to curb the Supreme Court in the 1950s, see: C. Herman Pritchett, Congress versus the Supreme Court: 1957-1960 (Minnesota, 1961). For a general overview of various efforts to curb the Court, see: Louis Fisher, Constitutional Dialogues (Princeton, 1988), chapter 6. C. Modes of Constitutional Interpretation Reading: Ducat, chapter 2; Thomas Grey, “Do We Have an Unwritten Constitution?” (excerpted version)[on Reserve]; speeches by Edwin Meese III and William J. Brennan [on Reserve]. Additional: For an introduction to the “interpretivist/non-interpretivist” debate, see: Thomas Grey, “Do We Have an Unwritten Constitution?” 27 Stanford L. Rev. 703 (1975). Owen Fiss, “Objectivity and Interpretation,” 34 Stanford L. Rev. 739 (1982). Ronald Dworkin, “Law as Interpretation,” 9 Critical Inquiry 179 (1982). This issue of Critical Inquiry includes a number of responses to Dworkin, including Stanley Fish’s “Working on the Chain Gang: Interpretation in the Law and Literary Criticism.” For competing theories of when it is legitimate to use “non-interpretive” review, see: John Hart Ely, Democracy and Distrust: A Theory of Judicial Review (Harvard, 1980). Michael Perry, The Constitution, the Courts, and Human Rights: An Inquiry into the Legitimacy of Constitutional Policymaking by the Judiciary (Yale, 1982). But cf. Perry, The Constitution in the Courts: Law or Politics? (Oxford, 1994) in which Perry revisits some of his arguments. Jesse Choper, Judicial Review and the National Political Process: A Functional Reconsideration of the Role of the Supreme Court (Chicago, 1980). For overviews of the debate over “original intent,” see: Jack N. Rakove, ed., Interpreting the Constitution: The Debate over Original Intent (Northeasterm 1990). Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (Knopf, 1997). For competing views about the nature of judicial decisionmaking, see: Benjamin Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process (Yale, 1921). Walter F. Murphy, Elements of Judicial Strategy (Chicago, 1964). J. Woodford Howard, Jr., “On the Fluidity of Judicial Choice,” 62 American Political Science Review (March 1968), 43-56. Saul Brenner, “Fluidity on the United States Supreme Court: A Reexamination,” 24 American Journal of Political Science (August 1980), 526-35. Harold Spaeth and Jeffrey A. Segal, The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model (Cambridge, 1993). Lee Epstein and Jack Knight, The Choices Justices Make (CQ, 1998). Forrest Maltzmann, James F. Spriggs II, and Paul J. Wahlbeck, Crafting Law on the Supreme Court: The Collegial Game (Cambridge, 2000). D. Congressional Power: An Introduction Reading: Ducat, chapter 3 (section a). Cases: McCulloch v. Maryland South Carolina v. Katzenbach City of Boerne v. Flores (it would help to review Oregon v. Smith) Missouri v. Holland Additional: For a look at the changing dynamics of congressional power over time, see: James L. Sundquist, The Decline and Resurgence of Congress (Brookings, 1981). E. Presidential Power: An Introduction Reading: Ducat, chapter 4 (section b – through page 218, and section c through page 247 and section d). Cases: Ex Parte Milligan Korematsu v. U.S. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer U.S. v. Curtis-Wright Export Corp. New York Times v. U.S. Additional: For competing views of presidential power, see: William Howard Taft, Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers (Columbia, 1916). Theodore Roosevelt, Autobiography (Macmillan, 1913), passim. Woodrow Wilson, Constitutional Government (1908). Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., The Imperial Presidency (Houghton Mifflin, 1973). Christopher S. Yoo, Steven G. Calabresi, and Anthony J. Colangelo, “The Unitary Executive in the Modern Era: 1945-2001,” 90 Iowa Law Review (2005), pp. 601ff. Ryan J. Barilleaux and Christopher S. Kelley, The Unitary Executive and the Modern Presidency (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2010). Classic early treatments of the presidency include: Edward Stanwood, A History of the Presidency (Houghton Mifflin, 1898). Edward S. Corwin, The Presidency: Office and Powers (New York University Press, 1957). For an excellent reader containing primary documents relating to the founding of the presidency, see: Richard J. Ellis, Founding of the American Presidency (Rowman & Littlefield, 1999). For case studies related to the cases we are reading this week: Maeva Marcus, Truman and the Steel Seizure Case (Duke, 1994). Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese-American Internment Cases (Oxford, 1983). F. Separation of Powers: Interbranch Conflict 1. Delegation, the Power to Investigate, Executive Privilege, and Presidential Signing Statements Reading: Ducat, chapter 3 (section b) and chapter 4 (pages 218-235 and 278). Cases: J.W. Hampton, Jr. & Co. v. U.S. Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan Schecter Poultry Corp. v. U.S. INS v. Chadha Clinton v. City of New York U.S. v. Nixon Additional: Some additional treatments of these issues include: Sotirios Barber, The Constitution and the Delegation of Congressional Power (Chicago, 1975). Barbara Craig, Chadha: The Story of an Epic Constitutional Struggle (Oxford, 1988). Louis Fisher, “The Legislative Veto: Invalidated, It Survives,” 56 Law & Contemp. Prob. 273 (1993). Jessica Korn, The Power of Separation: American Constitutionalism and the Myth of the Legislative Veto (Princeton, 1995). Louis Fisher, Presidential Spending Power (Princeton, 1975). Raoul Berger, Executive Privilege: A Constitutional Myth (Harvard, 1974). Mark Rozell, Executive Privilege (Johns Hopkins, 1994). Report of the ABA Task Force on Presidential Signing Statements, at www.abanet.org/media/docs/signstatereport.pdf 2. Appointment and Removal Powers Reading: Ducat, chapter 4 (section a). Cases: Myers v. United States Humphrey’s Executor v. United States United States v. Woodley Morrison v. Olson Additional: For treatments of the appointment and removal power, see: Joseph O. Harris, The Advice and Consent of the Senate (California, 1953). G. Calvin McKenzie, The Politics of Presidential Appointments (Free Press, 1981). John Anthony Maltese, The Selling of Supreme Court Nominees (Johns Hopkins, 1995). Michael J. Gerhardt, The Federal Appointments Process (Duke, 2000). James E. Gauch, “The Intended Role of the Senate in Supreme Court Appointments,” 56 Univ. of Chicago L.Rev. 337 (1989). Louis Fisher, “Congress and the Removal Power,” 10 Congress & the Presidency 63 (1983). II. THE DISTRIBUTION OF POWER BETWEEN THE NATIONAL GOVERNMENT AND THE STATES A. Commerce Clause: Early History and the Rise of Dual Federalism Reading: Ducat, chapter 5 (section through page 303, and section b through page 325). Cases: Gibbons v. Ogden U.S. v. E.C. Knight Stafford v. Wallace Houston, East & West Railway Co. v. U.S. Champion v. Ames Hammer v. Dagenhart Carter v. Carter Coal Additional: Classic early treatments include: Edward S. Corwin, The Commerce Power versus States’ Rights (Princeton, 1936). Felix Frankfurter, The Commerce Clause Under Marshall, Taney, and Waite (Chapel Hill, 1937). See also: William G. Ross, A Muted Fury: Populists, Progressives and Labor Unions Confront the Courts, 1890-1937 (Princeton, 1994). B. “Liberty of Contract” in the Dual Federalist Era Reading: Ducat, chapter 7 (section b). Cases: The Slaughterhouse Cases Munn v. Illinois Lochner v. New York Buck v. Bell Muller v. Oregon West Coast Hotel v. Parrish Additional: The “Lochner Era” is now widely criticized as a period of blatant judicial activism. See, for example: Robert Bork, The Tempting of America: The Political Seduction of the Law (Free Press, 1990), chapters 1-2. However, there are several revisionist accounts. For example: Howard Gillman, The Constitution Besieged: The Rise and Demise of Lochner Era Police Powers Jurisprudence (Duke, 1993). See also: Hadley Arkes, The Return of George Sutherland: Restoring a Jurisprudence of Natural Rights (Princeton, 1994). C. The Commerce Power Since 1937: The Rise of Cooperative Federalism Reading: Ducat, chapter 5 (section b, pages 326 to end, and section c). Cases: NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel U.S. v. Darby Wickard v. Filburn Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. Katzenbach v. McClung U.S. v. Lopez U.S. v. Morrison Gonzales v. Raich National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius Additional: Edward S. Corwin, “The Passing of Dual Federalism,” 36 Virginia L.Rev. 1 (1950). Paul R. Benson, Jr., The Supreme Court and the Commerce Clause, 1937-1970 (Dunellen, 1970). C. Herman Pritchett, The Roosevelt Court: A Study in Judicial Politics and Values (Macmillan, 1947). D. The Taxing and Spending Power as a Regulatory Device Reading: Ducat, chapter 5 (section d). Cases: McCray v. U.S., Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co., U.S. v. Butler, Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, South Dakota v. Dole, National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius E. State Regulation and the Dormant Commerce Clause Reading: Ducat, chapter 6. Cases: Jacobsen v. Massachusetts Cooley v. The Board of Wardens of the Port of Philadelphia Kassel v. Consolidated Freightways Corp. City of Philadelphia v. State of New Jersey ***** Keeping Up With Current Cases The easiest way to keep up with current decisions by the Supreme Court is through the Legal Information Institute’s website: http://supct.law.cornell.edu/supct/ or FindLaw: http://supreme.lp.findlaw.com/ Two annual publications are useful overviews of the previous year’s term. They also provide a preview of the current term: David M. O’Brien, Supreme Court Watch (Norton). Kenneth Jost, The Supreme Court Yearbook (CQ Press). Audio of oral arguments can be accessed from the web at: http://www.oyez.org/oyez/frontpage Briefs for cases pending before the Court (along with lower court opinions) can be found at FindLaw. All federal court decisions are available on Lexis/Nexis, as are all recent law review articles. The UGA Law School also has on-line copies of most major law reviews (including old editions) which can be accessed and printed at the library. Ask at the Reference Desk for more information. The Law and Politics Book Review is an excellent on-line source for keeping up with recent books in the field.