Essay: Public Education and the Humanities

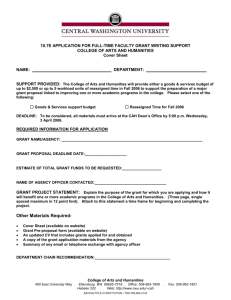

advertisement

P R I M A R Y A N D S E C O N D A R Y E D U C AT I O N I N T H E H U M A N I T I E S Public Education and the Humanities WILLIAM J. REESE F ew institutions are as central to the nation’s hopes for the future and aspirations for the common good than the public schools. Few have therefore received as much public investment and public scrutiny. To understand the place of the humanities in public schools today, as Part I of the Humanities Indicators Prototype1 seeks to do, requires an understanding of the main characteristics of public schools as they evolved over time and the current, dramatically new expectation that they lift academic standards for everyone, leaving no child behind. The statistical record that helps chart the fate of the humanities in the schools shows that a generation of reform has led to mixed, uneven results. This is not a cause for despair but simply a recognition that 1) fundamental change takes time and persistence; and 2) transforming and improving tens of thousands of schools in over 13,000 districts is a monumental task. When they were formed in the northern states in the pre–Civil War era, public schools assumed a multitude of responsibilities, not all of them academic. The most famous school reformer of the nineteenth century, Horace Mann (1796–1859) of Massachusetts, wrote that public schools were “the great equalizer of the conditions of men—the balance-wheel of the social machinery.”2 He and his contemporaries believed, like Thomas Jefferson before them, that people could not be ignorant and ex- pect to enjoy the blessings of civilization and representative government. Access to free schools, the theory went, allowed the economic system to remain fluid by enabling talented children from all backgrounds to rise. Mann and his contemporaries also passionately argued that schools could help promote literacy, eliminate poverty, hasten the assimilation of immigrants, and teach moral values, time discipline, and a hearty work ethic. These ideals (which have hardly disappeared from today’s classrooms) infused textbooks such as the blue-backed spellers of Noah Webster While no evidence supports the claim that pupils knew more in the past, the data on today’s students are alarming. and the assorted readers of the Rev. William Holmes McGuffey. Whether in the countryside, where the majority of children lived and attended one-room schools, or in the cities, teachers taught a mostly bare-bones curriculum, later called the basics, concentrating on reading, writing, and arithmetic, plus some geography, history, and occasionally drawing and science.3 Over the course of the twentieth century, public schools retained and even expanded their broad mission, building HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE © 2009 BY THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES upon tradition while changing some fundamental policies and practices. One-room schools in the countryside gave way to bigger consolidated facilities. Credentials for teachers and administrators rose dramatically. Children once routinely excluded from the benefits of public education, whether African-Americans in the South or special-needs children everywhere, increasingly attended school, thanks to the civil rights movement. Given their previously poor or nonexistent access to schools, such children faced daunting academic challenges but were part of a mighty explosion of enrollments. For example, about 6% of the adolescent population in 1890 attended high school, whose enrollments soon skyrocketed as immigrants filled the increasingly industrial work force and then jobs dramatically disappeared for teenagers during the Great Depression. New vocational courses appeared in many high schools in response to the presumed needs of the non–college bound, weakening the academic nature of secondary education, the traditional home of core humanistic subjects (e.g. English, history, and foreign languages).4 By midcentury, concerns about the direction and quality of mass education accelerated. Historically a state and local responsibility, schools quickly became the object of federal interest during the Cold War in the 1950s, when 1 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES their anemic academic nature, said critics, had allowed the Soviet Union the upper hand in the space race and military preparedness. Less than 1% of public school budgets came from the federal government in 1950, mostly through a few targeted programs such as vocational education. But attention to academic achievement, especially for gifted pupils in science, mathematics, and other academic subjects necessary for college admission and national defense, gained traction. The booming postwar economy also generated “rising expectations,” as citizens craved higher standards of living that seemed ever dependent on educational credentials. Complaints about underperforming schools were commonplace as an increasing number of citizens wanted to hold schools more accountable, whether for racially integrating society or for raising academic standards. Economists increasingly emphasized how education promoted human capital, essential to economic mobility and success. A 1965 television commercial, a public service announcement, underscored the centrality of schooling to material well being and the good life: “To get a good job, get a good education.”5 With the rise of the civil rights movement and Cold War, then, federal interest in lifting school achievement gained momentum. Measuring school performance, whether in the sciences or humanities, was nothing new. By the early twentieth century, achievement tests, aptitude tests, IQ tests, and many other forms of testing were ubiquitous. Test results helped place children in ability groups in elementary grades and formal tracks in many high schools. Pupils routinely took a variety of tests in each subject to determine their grades and chances for promotion. What was new was the hope that all children, and not the tiny number of gifted ones, should do well at school, an idea born during the Great Society years of the 2 1960s. Legislators who approved landmark legislation such as the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which aimed to raise school achievement among the nation’s poorest children, mandated follow-up studies to assess how well such reforms worked. Concerns throughout the 1970s over declining scores on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), teacher strikes, and accelerating levels of pupil violence and drug use led a new generation of Republicans to emphasize even more the need to promote higher academic standards for all pupils.6 Various indicators show that the achievement gaps between different ethnic and racial groups–which school reformers have tried to narrow since the time of the Great Society–remain stubbornly wide. Evolving bipartisan support among Republicans and Democrats for raising standards and measuring school performance to assess reform initiatives is inexplicable apart from these various historical trends. They help provide a context in which to assess what has been documented in the current Humanities Indicators. The pressure on schools to lift academic scores in key academic subjects, including in the humanities, arose from a number of overlapping developments. The influential national report, A Nation at Risk (1983), sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education during Ronald Reagan’s first presidential term, condemned schools for their cafeteria-style curriculum and lax standards, holding the schools responsible (fairly or not) for a deteriorating economy.7 During the same period, governors’ associations and business groups throughout the nation called for an increase in graduation requirements, a beefed-up academic core, and tougher disciplinary policies. George H. W. Bush, a self-styled “education president,” along with his successor, Bill Clinton, pressed for national educational goals, resulting in Goals 2000 and the promise, among other things, to make the nation’s schools the best in the world in mathematics and science. The No Child Left Behind Act, a Republican initiative that initially enjoyed strong bipartisan support, mandated testing and evaluation to raise standards across the board.8 How well have schools responded to these reform movements in terms of the humanities? Strong reading and writing skills are essential to success in many school subjects, including the humanities. Despite all of the emphasis on raising standards for everyone, a generation of school reform has produced uneven, mixed results. Consider first the issue of reading performance of 9-year-olds from 1971 to 2004 on tests given by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP, created in 1969). At the highest end of the performance spectrum there has been only slight improvement whereas at the intermediate level there was an impressive leap of 11 percentage points (Figure I-1a).9 However, for the same period, 13-year-olds showed much continuity, not improvement, in their level of achievement (Figure I-1b). Much the same can be said for 17-year-olds at all three performance levels (Figure I-1c). Writing performance is also crucial to overall school success. NAEP test results for 1998 and 2002 showed that a majority of 4th, 8th, and 12th graders could write at a basic level, but the level of improvements that 4th and 8th graders made over that time period in the proficient category was not achieved in high school. In 2002, 26% of 4th graders, 29% of 8th graders, but only 22% of 12th graders wrote at the proficient level (Figure I-2). HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES Often it is said that those who are ignorant of history are doomed to repeat it and cannot participate fully in a democratic republic. If true, the indicators on pupil knowledge of history and civics are cause for concern. While no evidence supports the claim that pupils knew more in the past, the data on today’s students are alarming. Consider the NAEP scores on U.S. history achievement in 1994 and 2003. While about half of 4th and 8th graders had a basic knowledge of American history and showed some gains over time, only one-third of 12th graders scored at the basic level. Over half of the seniors scored below basic (Figure I-3). The same phenomenon noted in other subjects, that of lesser achievement at the higher grade levels, surfaced in the 2006 NAEP civics test: only 66% of high school seniors performed at a basic level or better compared to 73% of fourth graders and 70% of 8th graders (Figure I-4a). the depth and rigor necessary for higher achievement, the enrollment trends in Spanish are salutary. Since the early 1980s, academic course-taking in the contemporary high school has shown modest overall improvement. According to transcript studies from the U.S. Department of Education covering 1982 to 2000, the number of credits taken in vocational subjects has noticeably decreased, and the number in academic alternatives has increased.11 States and local school districts, responding to widespread complaints about poor academic quality even before A Nation at Risk, labored to im- Foreign-language instruction had been a mainstay in public high schools since the nineteenth century but suffered calamitous enrollment declines over the first half of the twentieth century.10 However, since the 1980s Spanish, thanks to demographic change and the perceived utility of this language, has grown more popular, as reflected in dramatic gains in enrollment. Other European languages have fared less well, and enrollments in Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, and Russian, for example, are relatively small (Figure I-7a). The good news is that over the last generation a much higher percentage of high school graduates have completed four years of course work in a foreign language. Only 4.5% of all graduates had done so in 1982 compared to 7.8% in 2000 (Figure I-7b). humanities courses. Although considerable room remains for improvement in the number of pupils pursuing foreign languages with HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE The results of various school reforms, as shown by the Humanities Indicators Prototype, have been uneven, but modest progress has been made since the 1980s in expanding access to more academic and prove their secondary schools. This benefitted the humanities, which have seen a noticeable if sometimes modest rise in enrollments in English, social studies, and foreign languages since the 1980s (Figure I-6). Transcript studies cannot assess the content or quality of the curriculum, but the trends were nonetheless notable. The inability of high school seniors to perform better on NAEP reading and writing exams, then, requires explanation. Similarly, indicators are needed to assess the achievement of the many children with access to various humanities courses who are streamed into special education. We also need more knowledge about humanities instruction in schools in different locales—for example, in cities, suburbs, small towns, and rural areas—and about the influence of re- forms such as No Child Left Behind on the curriculum, from the teaching of the three R’s to the arts. Various indicators show that the achievement gaps between different ethnic and racial groups–which school reformers have tried to narrow since the time of the Great Society–remain stubbornly wide. SAT scores are one of many examples of this disturbing reality. Mean SAT scores dramatically declined from the late 1960s through the early 1980s, fueling considerable public debate over the causes and solutions to correct the problem. Once the decline halted, mean verbal scores have generally remained in the 500–510 range. Mean math scores, however, have improved overall from their low point in the early 1980s, hitting 520 in 2005 (Figure I-5a). Persistent gaps, however, separate whites and African Americans, whose mean score on the verbal and critical reading component of the SAT was considerably lower than that for whites in 1992 and 2002 (Figure I-5b). Racial and ethnic disparities were also evident in the 2006 SAT writing scores of college-bound seniors (Figure I-5c). While the dramatic rise in the number of Advanced Placement Exams in the humanities taken per 11th and 12th graders, from 8.8 exams per 100 11th and 12th graders in 1996, to 16.9 in 2005, is impressive, these courses disproportionately profit white middle- and upper-class pupils, adding to and not narrowing the racial divide (Figure I-8b). The quality and character of the teaching force clearly influences academic outcomes, but their precise impacts are more difficult to assess. Drawing upon data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the Humanities Indicators Prototype provides useful information on some of the academic and professional qualifications of high school teachers. For example, in 1999–2000, 80% of high school stu3 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES dents taking arts and music and 70% of students in English courses were taught by faculty who were both certified to teach and had majored in the taught subject in college. That dropped to a little over half for students taking foreign languages and under 40% for students of history (Figure I-9a). Except in the case of arts and music, the percentages of students who were taught by faculty with both certification and a major in the subject taught were substantially lower at the middle school level (Figure I-9b). (High school teachers have long been subject-matter specialists, unlike teachers of the lower grades.) While the percentage of nonwhite pupils in the public schools has dramatically risen since the 1960s, Hispanics and AfricanAmericans remain underrepresented in the teaching force (Figure I-10c). Attracting the best and the brightest to public school teaching, especially in schools with high percentages of poor, minority, and special needs children, will be a continual challenge. Revolutions are rare in education, and a knowledge of history helps put recent trends in the humanities in the public schools in context. From their inception, schools have been asked to per- 4 form innumerable functions, including training the mind as well as more immediately preparing pupils for the work force. With the collapse of the industrial economy and the replacement of industrial jobs with low-wage jobs in the service economy, citizens understandably turned to the schools to try to solve pressing social problems. Over the last generation—a relatively short period of time—many policymakers, politicians, and educators have tried to make public schools both inclusive and excellent. The civil rights movement led the way in bringing more children of color, and those with special needs, into the embrace of the public system. The results of various school reforms, as shown by the Humanities Indicators Prototype, have been uneven, but modest progress has been made since the 1980s in expanding access to more academic and humanities courses. As recently as the 1950s, only gifted children were expected to receive a high quality academic education. In today’s global economy, such thinking is untenable. Though much more must be done to raise achievement levels in reading, writing, and various academic subjects, America’s high schools seem especially remiss in not sustaining the often modest progress that has been made in lifting school achievement at different times in the lower grades. That high school teachers more often than their counterparts in the lower grades major in the particular subjects they teach makes their inability to raise achievement levels puzzling. The indicators cannot explain why improvement or failure occurs on any grade level or in any particular subject, but they are an essential part of our understanding of the nature of public schooling. Without them, charting the place of history, English, foreign languages, and the arts in the nation’s schools and beginning to understand what role the humanities will continue to play in our society will be difficult. William J. Reese is the Carl F. Kaestle WARF Professor of Education Policy Studies and History at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. His publications include Rethinking the History of American Education (co-editor) (2007), America’s Public Schools: From Common School to ‘No Child Left Behind’ (2005), and The Origins of the American High School (1995). He is a member of the National Academy of Education. HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES NO T ES 1 Humanities Indicators Prototype, Part I. Primary and Secondary Education in the Humanities, www.humanitiesindicators.org (American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2008); hereafter cited as HIP. 2 Twelfth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Board (Boston: Cutton & Wentworty, 1849), 69. On Mann’s wide-ranging views on education and society, see Jonathan Messerli, Horace Mann: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972). 3 On the creation of public schools, see Carl F. Kaestle, Pillars of the Republic: Common Schools and American Society, 1780–1840 (New York: Hill & Wang, 1983); and William J. Reese, America’s Public Schools: From the Common School to ‘No Child Left Behind’ (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005). 4 See William J. Reese, The Origins of the American High School (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995). 5 On the postwar developments, see James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). 6 Reese, America’s Public Schools, ch. 7. 7 National Commission on Excellence in Education, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform (Washington, DC: GPO), available online at http://www.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/index.html. 8 On the evolution of the federal role in education, see Carl F. Kaestle, “Federal Education Policy and the Changing National Polity for Education, 1957–2007,” in To Educate a Nation: Federal and National Strategies of School Reform, ed. Carl F. Kaestle and Alyssa E. Lodewick, 17–40 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007). 9 All figures can be found in the HIP, Part I, and are reproduced at the end of this essay. 10 John Francis Lattimer, What’s Happened to Our High Schools? (Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press, 1958), 26. 11 HIP, Part I Indicator I-6. Credits Earned by Graduating High School Seniors. For the period 1890 to 1995, see David L. Angus and Jeffrey E. Mirel, The Failed Promise of the American High School, 1890 – 1995 (New York: Teachers College Press, 1995), 176-182. HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 5 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 6 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 7 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 8 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 9 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 10 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 11 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 12 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 13 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 14 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 15 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 16 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 17 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 18 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 19 PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES 20 HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE PUBLIC EDUCATION AND THE HUMANITIES HUMANITIES INDICATORS PROTOTYPE 21