Toward a Cohesive Approach to Appellate

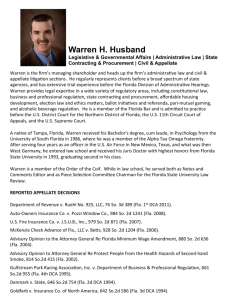

advertisement