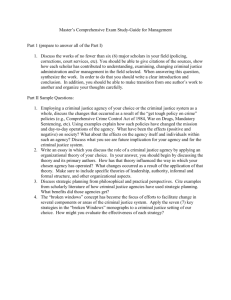

Criminal - Alberta Justice

advertisement