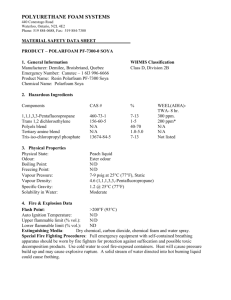

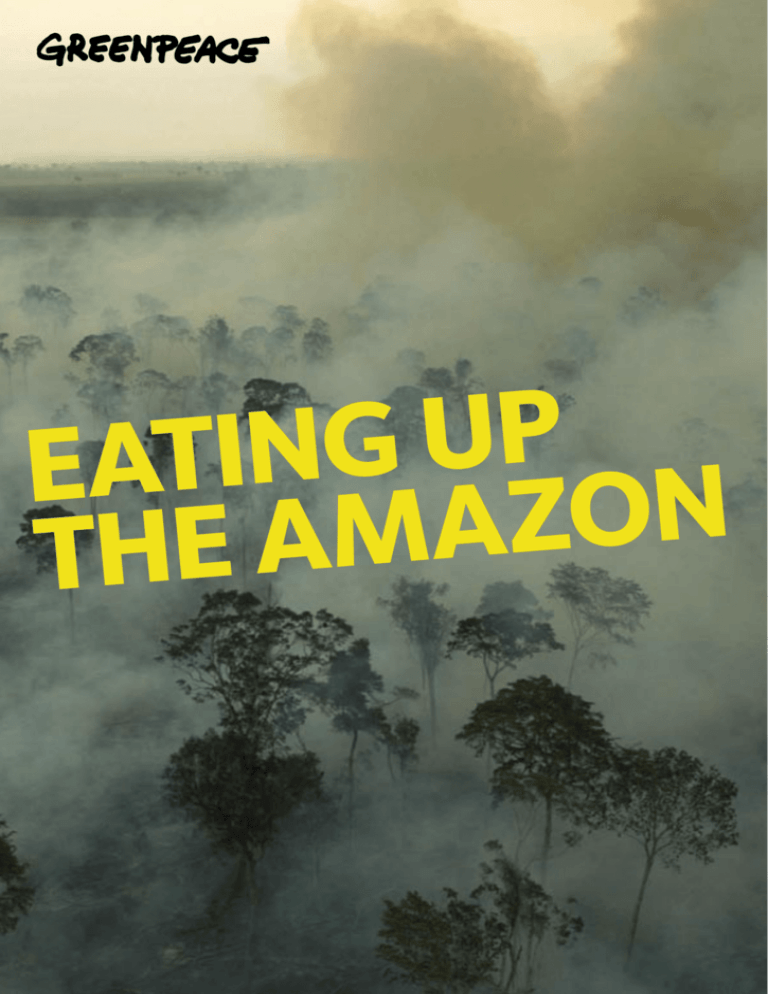

Eating Up The Amazon

advertisement