Gifts from the Father of the Kindergarten

advertisement

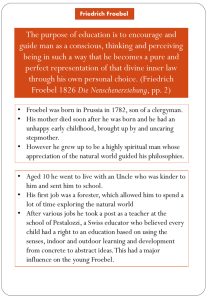

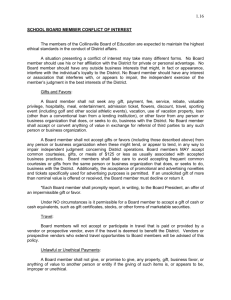

Gifts from the Father of the Kindergarten Carol Woodard State UniversityCollege at Buffalo Buffalo, New York The ElementarySchoolJournal Volume 79, Number 3 ? 1979 by The University of Chicago. 001 3-5984/79/7903-0011$00.75 Except for an occasional textbook reference as "the father of the kindergarten" Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852) remains a shadowy figure to many early childhood educators. His status is especially puzzling when one considers that he was once the acknowledged leader in the field. More than 125 years ago he pioneered many of the basic tenets of early childhood education-the value of play, self-activity, and social interaction. He had a firm grasp of many current concepts. He advocated the use of concrete materials for exploration, a variety of activities geared to the child's interest, the sequencing of materials, and he stressed the importance of language in the learning process. Add to these ideas his avant-garde nurturing of mother-infant interactions and homeschool relations, and his present obscure position appears all the more perplexing. Perhaps part of Froebel's present obscurity is due to his own writings, which are laced with vague, symbolic terms that discourage readers. A major part of his obscurity, however, can be attributed to a "bad press," which resulted from the rigid use of his methods, often by dedicated followers caught up in the rapid expansion of the American kindergarten movement at the close of the nineteenth century. Knowledgeable Froebelians were involved in teacher training, but many trainees learned Froebelian methods from inexperienced interpreters, and much was lost in the translation. Froebel left no clear methodology in his own writings, concentrating instead on his scholarly interest in mysticism. Consequently, misguided followers often relied on the structured use of FROEBEL materials that Froebel had designed to be used in more exploratory ways. Despite such problems, early childhood education in the USA is built on a Froebelian foundation, and his ideas, still flourishing in the classroom, sound amazingly modern to today's teacher. Froebel was brought up in a secluded village parsonage in central Germany by a formidable father and a rejecting stepmother, never experiencing the warm, family-centered atmosphere he sought for the kindergarten. As an adolescent, he was apprenticed to a forester and developed an intense love of nature, which later pervaded his writing and teaching. During the ensuing years, Froebel tried a variety of occupations and intermittently attended several universities, where he studied the natural sciences and the German philosophers. Gradually, Froebel adopted a philosophical view of the universe in which man and nature were components, developing according to the law of unity. This emphasis on the unity of all living things-a oneness linking nature, man, and Godextended to Froebel's educational theory. The child, like a plant, developed or unfolded according to laws inherent in his nature. The teacher, like a gardener, created an environment (a kindergarten, or "children's garden") that would nurture this unfolding process and help the child relate and unify his experiences. Although Froebel lacked formal training, he was a natural teacher and found his way to the classroom, only to feel repressed routine. Seeking by its constraining alternatives, he studied with the noted educator, Johann Pestalozzi, and, though impressed, still struggled with questions of methodology. A brief period in the army proved a socializing influence for the solitary Froebel, and in 1816 he opened his own school at Keilhau. His five nephews formed the initial student body, and the curriculum concentrated heavily on arithmetic, geometry, and German, supplemented by nourishing food, simple cloth- 137 ing, and vigorous outdoor experiences. Although the school was educationally successful, it was plagued by financial difficulties, and Froebel, never renowned as an administrator, was eased from its management. After teaching in Switzerland and observing day nurseries in Berlin, he became completely involved with a new concept: education designed for the very young child. In 1837, now in his midfifties, Froebel established the first kindergarten in an old powder mill near Blankenburg, accepting children from one to seven years of age. He devoted the ensuing years of his life to the school, to traveling about Germany and founding other kindergartens and training teachers to staff them. Originally, Froebel had intended to train men for the kindergartens; but, finding limited interest, he trained young, unmarried women instead and opened new doors for them in education. During this period, Froebel developed for young children a series of teaching materials and activities that were commonly used in American kindergartens in the early 1900's and are still used in Europe. Built on Froebel's belief in the educative value of play, these materials and activities were to encourage learning by doing while familiarizing the children with various laws of life. With this lofty goal in mind, Froebel designed three types of materials/activities: "gifts," "occupations," and "mother plays." "Gifts" were concrete materials to be manipulated by the children and included block sets, tablets, wooden splints, rings, and natural objects such as beans, pebbles, and shells. "Occupations" were manipulative activities to be performed by the children. These activities included embroidery, drawing, paper folding, cutting, and interlacing, and working with clay. "Mother plays" consisted of a series of stories, songs, and games originally compiled for mothers to use with their small children in the home but also used in the kindergarten. THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL 138 The materials called "the gifts" were sequential in nature, moving from simple to complex. Each child had his own set of gifts, which were kept individually in wooden boxes with sliding lids. When the child was given a gift to play with, he was allowed to explore it as long as he liked, usually on a table marked with a grid of one-inch squares. If interest lagged, the teacher would ask leading questions, for Froebel encouraged children to observe the gifts carefully, to recognize similarities and differences, and to classify the properties. Although various versions of the gifts have evolved through the years, the earlier ones illustrate their potential. The first gift, originally intended for infants and toddlers, consisted of six woolen balls with strings attached, ranging in color from blue to violet. This gift could be used to investigate color, material, texture, motion, or direction, while the spheres were to symbolize the unity of the universe. The second gift consisted of three wooden geometric solids: a sphere, a cube, and a cylinder or roller. O Gift No. 2 Froebel used this gift to illustrate his philosophical concept that opposites (the sphere, which moved, and the cube, which was stable) could be united by intermediaries (the cylinder, which combined both movement and stability). In probing the possible uses of the gift, the child might observe changes in form. The cube, for example, appeared to be a cylinder when rotated from a string attached to a staple in the center of its face. The third gift was a two-inch wooden cube that could be subdivided into eight smaller cubes. Gift No. 3 The fourth gift was a two-inch cube composed of eight rectangles, while the fifth consisted of twenty-seven one-inch cubes (three bisected and three quadrisected), which together formed a threeinch cube. Gift No. 4 Gift No. 5 The third, fourth, and fifth gifts were each presented as a whole cube, separated into parts during play and always returned to their whole form, reflecting Froebel's theme of unity. The fact that these gifts provided opportunities to experience mathematics was intentional because Froebel considered mathematics a starting point in education, an observable expression of the conformity to law. Later gifts included colored square and triangular tablets (introducing the plane), wooden splints (the line), metal rings (the curve), and natural objects such as beans, pebbles, and seeds (the point). Beginning with the third gift, the children could use the gifts in three ways to create what Froebel termed "forms of life," "forms of beauty," and "forms of knowledge." "Forms of life" were constructions of various everyday objects. "Forms of beauty" were artistic symmetrical designs created by the child. "Forms of knowledge" were activities performed to demonstrate mathematical properties. JANUARY 1979 139 FROEBEL the gift. In some arrangements, outer parts were moved around a center core; in other arrangements certain parts were turned over. gift had its own series of life, suggested forms or patterns-of beauty, and knowledge-which were to be followed and which increased in complexity. A child using a gift as a form of life might start by building familiar objects of his own choice. Froebel encouraged this type of inventive play. At times the older children interacted with the younger to share ideas and arrangements. Eventually, however, the child would progress to duplicating some of the objects from the patterns provided for the particular gift he was manipulating. Each L;4 When knowledge forms were used, the child arranged and grouped a gift to analyze its mathematical properties. At first, exploration might focus on division (fractions) rather than addition and subtraction. With the teacher's guidance, the child could divide the fourth gift into two equal parts and then into quarters and eighths. Actions were always accompanied by appropriate words ("one whole equals two halves"; "two halves equal one whole") because Froebel recognized the rebetween and lationship language learning. Addition could also be taught by letting the child count: Castle -7Locomo Locomotive __/ ::71 Gift No. 3 Forms of Life J Triumphal Arch L I I Merry-go-round Gift No. 4 Forms of Life In building life forms, it was considered essential that all the pieces in the gift be used so that the parts contributed to the unified structure. When a gift was used as a beauty form, the child's interest focused on design, symmetry, and balance. To duplicate the sequential design patterns accurately, it was necessary to closely observe the relationships between the various parts of Gift No. 4 Forms of Beauty Gift No. 3 Forms of Beauty I Z1 I One and one are two. I I Ii Two and one are three. Three and one are four. In subtraction the order was reversed. Used in still another manner, the fourth gift might be manipulated to answer the question, "How many squares can you make with the eight rectangles?" m m One Large Square or m m Four Small Squares Generally, the younger children concentrated on the less complex forms of life, beauty, and knowledge. 140 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL In addition to the gifts, Froebel incorporated activities known as "occupations" in his kindergarten curriculum. The activities included perforating (making designs by poking holes in paper), sewing outlines on cards, drawing, cutting, folding, and weaving paper, and working with clay. These crafts and table games were an extension of the gifts, helping the children express ideas they had explored by using the gifts. Froebel's final group of materials/ activities were the "mother plays," simple, spontaneous songs, poems, and games that he had observed mothers using with their small children, such as the universal favorite, Pat-a-cake. These were published in the illustrated book, Mutter-und-KoseLieder. Froebel viewed the kindergarten as a continuation of the gentle, natural instruction of the mother, and the mother plays were intended to support this type of interaction related to home activities. Unfortunately, followers of Froebel used the mother plays with much older children. Even when the mother plays were age appropriate, the provincial themes and the intricate illustrations were not adapted for the American setting. It is the misuse of Froebel's materials that makes it difficult to evaluate them objectively. Certainly, our current knowledge of child development indicates that the gifts do not symbolize universal truths to the young child. The toddler may appreciate the color of the yarn ball or its softness, but hardly relates it to the unity of the universe. Critics contend that although Froebel advocated play, he actually enclosed the child within the structured use of gifts. It is impossible to know exactly how Froebel used the gifts, but evidence seems to indicate that Froebel was more moved by a spirit of experimentation than his followers were. Froebel underscored system and method, but mechanical drill was never intended to replace exploration. The gifts and the occupations must be viewed in the context of their time; in their day, they were considered emancipating. Imitation, valued as part of creativity, was used by Froebel to provide basic principles to stimulate the child's own original work. Frank Lloyd Wright used the Froebelian gifts as a child, and his imagination was sparked in just such a way (1). Yet, Froebel's followers worked with the gifts almost religiously, and the Froebelian kindergarten in America became synonymous with regimentation. John Dewey did not even use the term "kindergarten" to identify the preprimary groups at the University of Chicago Laboratory School in the late 1890's. Soon after, a bitter struggle emerged between the "traditional" Froebelians and the more liberal educators who were influenced by the new scientific study of children. Science triumphed, and gradually the Froebelian gifts faded from the American kindergarten. Other contributions by Froebel have remained, helping to shape the direction of our classrooms, for Froebel was an innovator. Not only did he recognize the importance of development in the earliest years, but he created a special environment to nurture growth. Applying the educational theory that each stage of growth evolves from the previous one, Froebel designed a sequential curriculum to foster this unfolding process. At a time when play was little understood and even considered an inducement to idleness, Froebel was committed to play as a way of instruction. Speaking of the kindergarten, Froebel said, "It will be an institution where children instruct and educate themselves and where they develop and integrate all their abilities through play, which is creative self-inself-activity and spontaneous struction" (2). At a time when other classrooms were dominated by memorization and recitation, Froebel emphasized learning by doing and substituted gentleness for sternness. He had a deep respect for the individuality of each child. Education was JANUARY 1979 FROEBEL involvement based on the child's needs, interests and abilities. Through involvement the child could discover the nature of things and construct an understanding of his environment. Froebel provided a variety of materials that were to be handled, examined, and explored until all the inherent meanings were investigated and conclusions drawn. The manipulation of concrete objects was always to supplant or supplement the use of words and books. Questions, conversations, discussions, as well as songs and chants, were used with the gifts to further observational skills and language development. Words were linked to the child's endeavors while the teacher's role was to guide self-activity rather than to instruct directly. Learning was to be integrated, interwoven among subjects. Singing, circle games, gardening, cooking, dramatics, nature study, and storytelling were part of the curriculum. The total development of the child-social, emotional, physical, and intellectual-was valued. Because social development was dependent on the child's relations with others, interaction and cooperation among children were stressed. The child was always considered a part of the whole-the group. 141 Froebel further anticipated current in education and even inparent thought fant education by encouraging the parent to be the child's teacher and by providing supportive materials. It seems unfortunate that the negative reactions against Froebel's materials and followers have overshadowed his influence on today's early childhood programs. His gifts to these programs did not come in polished wooden boxes. Froebel's lasting value of play, gifts were his ideas-the and social interaction-ideas self-activity, that forged a unique atmosphere for the preprimary classroom and made it a place refreshingly oriented to activity and discovery, a very special place for children-a child's own garden. References 1. D. Donevi. "The Education of a Genius: Analyzing Major Influences on the Life of America's Greatest Architect,"YoungChildren,23 (March, 1968), 223-40. 2. I. Lilley (editor).FriedrichFroebel.A Selection of Writings, p. 128. London: Cambridge UniversityPress, 1967.