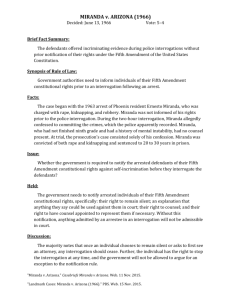

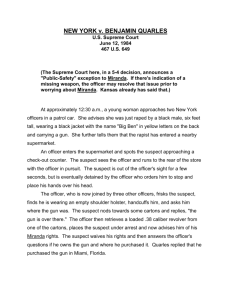

The Political Foundations of Miranda v. Arizona and the Quarles

advertisement