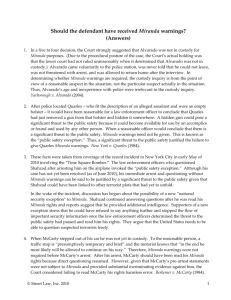

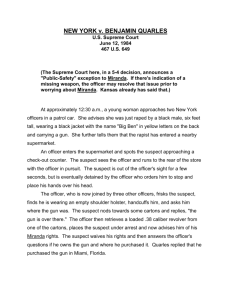

VIEW PDF - Fordham Law Review

advertisement