In Personam Liability & Ship Arrest: Singapore Law

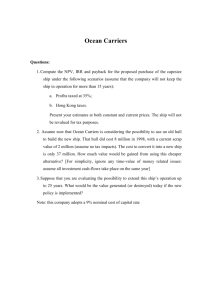

advertisement