Collaboration and Content in the Symphonie fantastique Transcription

Author(s): JONATHAN KREGOR

Reviewed work(s):

Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Spring 2007), pp. 195-236

Published by: University of California Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2007.24.2.195 .

Accessed: 23/01/2012 05:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Musicology.

http://www.jstor.org

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 195

Collaboration and Content

in the Symphonie fantastique

Transcription

J O N AT H A N K R E G O R

I

t was Charles Hallé who best captured the most

famous performance of Franz Liszt’s solo piano transcription of Hector

Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique:

To return to my own experiences in 1836, I have to relate that a few

days after having made the acquaintance of Chopin, I heard Liszt for

the first time at one of his concerts, and went home with a feeling of

The present article has been enriched considerably through

valuable advice and close readings by Detlef Altenburg, Mark

Evan Bonds, Jon Finson, Dana Gooley, Thomas Forrest Kelly,

Evelyn Liepsch, Rena Charnin Mueller, and Karen Painter. I am

especially grateful to Sean Gallagher and Alexander Rehding for

their indefatigable support. Consultation of primary-source materials at the Goethe- und Schillerarchiv was made possible by a

grant from the Stiftung Weimarer Klassik.

Abbreviations

C.G.I = Hector Berlioz, Correspondance Générale I, ed. Pierre Citron

(Paris: Flammarion, 1972).

C.G.II = Hector Berlioz, Correspondance Générale II, ed. Frédéric

Robert (Paris: Flammarion, 1975).

C.G.IV = Hector Berlioz, Correspondance Générale IV, ed. Pierre

Citron, Yves Gérard, and Hugh J. Macdonald (Paris: Flammarion, 1983).

Liszt/d’Agoult = Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult, Correspondance,

ed. Serge Gut and Jacqueline Bellas (Paris: Fayard, 2001).

NZfM = Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.

D-WRgs = Weimar, Goethe- und Schillerarchiv

US-Wc = Washington, D.C., Library of Congress, Music Division

The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 24, Issue 2, pp. 195–236, ISSN 0277-9269, electronic ISSN 1533-8347.

© 2007 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests

for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’s

Rights and Permissions website, http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp. DOI: 10.1525/

jm.2007.24.2.195.

195

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 196

the journal of musicology

thorough dejection. Such marvels of executive skill and power I could

never have imagined. . . . The power he drew from his instrument was

such as I have never heard since, but never harsh, never suggesting

“thumping.” His daring was as extraordinary as his talent. At an orchestral concert given by him and conducted by Berlioz, the “Marche

au supplice,” from the latter’s “Symphonie fantastique,” that most gorgeously instrumented piece, was performed, at the conclusion of

which Liszt sat down and played his own arrangement, for the piano

alone, of the same movement, with an effect even surpassing that of

the full orchestra, and creating an indescribable furore. The feat had

been duly announced in the programme beforehand, a proof of his

indomitable courage.1

196

In one epochal event, Hallé succinctly tied together several strands of

Liszt’s virtuosity: his bold, commanding artistic profile (much stronger,

apparently, than that of Chopin), a nuanced technique that not only

transcends the clichés of the Parisian virtuosos but allows him literally

to conjure unheard-of sounds from his instrument, and an ability to

overwhelm his audience with a power greater than any orchestra could

ever realize. In short, no other pianist—hence Hallé’s dejection—could

have achieved such a performance.

It is of little consequence that several details of this account are inaccurate. Berlioz was not the conductor when Liszt played the second

and fourth movements at the transcription’s premiere in 1834 (it was

actually François-Antoine Habeneck), nor did he perform the fourth

movement after an orchestral performance when Berlioz conducted in

1844. In fact, Liszt’s performance of portions of the work in 1836 did

not include the orchestral version at all.2 Spotty memory aside, however, Hallé’s point is clear: That day Liszt and his “orchestra” of ten

fingers mobilized sounds of such strength—indeed violence—that

Berlioz’s orchestra was utterly subdued, if not annihilated altogether.

Hallé’s report continues to remain popular because it evocatively recreates Liszt’s first duel, with the courageous, heroic victor flaunting what

Dana Gooley has called Liszt’s “military aura,” a facet of the performer

that would become integral to his triumphs on stage over the next

15 years.3 But at an even more substantive level, Hallé’s story success1 C. E. and Marie Hallé, eds., Life and Letters of Sir Charles Hallé (London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1896), 37–38.

2 Adrian Williams seems to have been the first to discuss, perhaps even note, this

discrepancy. He suggests the 4 May 1844 concert as the only plausible one in which Hallé

heard Liszt perform part of the Symphonie fantastique under similar circumstances. If this

is true, Hallé listened to an execution of the second movement, not the fourth. See

Adrian Williams, Portrait of Liszt: By Himself and His Contemporaries (Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1990), 84–85.

3 Dana Gooley explores the ubiquitous military imagery of Liszt’s virtuosity in his

The Virtuoso Liszt (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004), chap. 2.

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 197

kregor

fully unites two seemingly independent strands of the pianist’s persona:

the fiery, dueling Liszt and the sympathetic arranger Liszt, the artist responsible for transferring Beethoven’s symphonies, Schubert’s lieder,

and selections from Wagner’s operas to the keyboard with ostensibly

little or no loss of effect. Indeed, Hallé’s account seems an outright

affront to the artist and composer Berlioz, suggesting that Liszt’s

arrangement of Berlioz’s march was even more powerful, more terrifying (that is, more suited to the program of the “Marche au supplice”),

and better “orchestrated” than the original, a position with which many

would take issue today.

The enduring popularity of Hallé’s recollection illustrates how

Liszt’s biographers, in a tradition that extends back to Robert Schumann’s 1835 review of the work in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, have

continued to afford the arrangement of the Symphonie fantastique a primacy of place among his more than 300 similar productions for solo piano.4 Alan Walker wonders of Berlioz’s work in his 1983 Liszt biography: “Is there more idiosyncratic music anywhere?” His answer comes

in the form of a musical example, measures 97–104 of the “Marche au

supplice,” which not only “would have rolled across the halls like peals

of thunder” but “which, at times, approaches the accuracy of a mirror

held up to the object it seeks to reflect.”5 Walker here waxes lyrical over

a topic that—like the Lisztian duel—has become a staple in Liszt scholarship. Indeed, Humphrey Searle, writing almost 20 years before

Walker, calls Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique “surely one of the most unpianistic works ever written!” He, too, supplies the same eight measures

from the “Marche” as a self-understood explanation of Liszt’s superhuman ability to “recast the texture [of Berlioz’s original] as to make

the piano give an orchestral effect.”6

There is no doubt that the Symphonie fantastique arrangement offers

a snapshot of just how far Liszt’s already impressive keyboard technique

and keen investigation of the pianoforte’s sonic potential had progressed

by 1833. Liszt himself considered the transcription his most ambitious

work to date, and he would not publish compositions of such scope until

almost half a decade later, when he launched the Vingt-quatres grandes

4 See Robert Schumann, “ ‘Aus dem Leben eines Künstlers.’ Phantastische Symphonie

in 5 Abtheilungen von Hector Berlioz,” NZfM 3/1, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 (3 July, 31 July–14

August 1835): 1–2, 33–35, 37–38, 41–51. Two valuable English translations of Schumann’s review exist: Hector Berlioz, Fantastic Symphony, ed. Edward T. Cone (New York:

Norton, 1971), 222–48; and Robert Schumann, “Review of Berlioz: Fantastic Symphony,”

in Music Analysis in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Ian Bent (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ.

Press, 1996), 2:161–94.

5 Alan Walker, Franz Liszt: The Virtuoso Years, 1811–1847 (Ithaca: Cornell Univ.

Press, 1983; rev. ed. 1988), 180–81.

6 Humphrey Searle, The Music of Liszt (New York: Dover, 1966), 7–8.

197

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 198

the journal of musicology

198

études (retitled for the 1851 publication as the Etudes d’exécution transcendante), the Schubert song arrangements, and the first batch of

opera fantasies in the wake of what was to become a decade-long European tour. Even though Liszt rarely performed the Symphonie fantastique

arrangement publicly during this period (and even then only a selected

movement or two), the work is exemplary of a practice ascribed to Liszt

by Searle, Walker, and many other commentators—namely, Liszt’s musical dissemination of works written by his musical heroes and contemporaries. Walker’s statement can be taken as representative: “His chief motive was to help the poverty-stricken Berlioz, whose symphony remained

unknown and unpublished. Liszt bore the expense of printing his keyboard transcription himself, and he played it in public mainly to popularize the original score.”7

While certainly true to a degree, such accounts often reduce Liszt’s

involvement to one of routine and passive promotion, a one-sided exchange whereby Berlioz benefits from Liszt’s toils. Moreover, they overlook the fundamental importance that arrangements played in shaping

Liszt’s general artistic aesthetic as well as his compositional and literary

endeavors during the 1830s and beyond. It is a testament to the biographical allure of the charitable arranger and performer that few

scholars have ventured to explain exactly how Liszt performing his own

reduction alongside the original could raise awareness of Berlioz’s full

score. Instead, the inherited histories of the Liszt-Berlioz relationship

and the Symphonie fantastique have helped shape a seemingly analytic

truth about Liszt’s musical arrangements: Since we understand their

chief role to be one of dissemination and by extension preservation, fidelity to the original work becomes its most prized feature.

But transcriptions always document musical intersections, and pigeonholing Liszt’s keyboard arrangements as abstract paragons of

musical reproduction often divorces them from—indeed, denies us—

the milieu of their creation and early dissemination. Conceiving the

history of Liszt’s Symphonie fantastique arrangement as a series of often

independent reactions by its creators and auditors helps reveal a more

complex history, one that involves two of the most important artists of

the Romantic era. Correspondence as well as manuscript evidence sug7 Walker, Liszt: The Virtuoso Years, 180. Observations by Serge Gut (Franz Liszt [Paris:

Éditions de Fallois/L’Age d’Homme, 1989], 37) and D. Kern Holoman (Berlioz [Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1989], 110), penned around the same time as Walker’s biography, similarly restate Humphrey Searle’s formulation that “the purpose of the transcription was of course to help Berlioz at a time when he found it difficult to get orchestral

performances of his works: Liszt not only played it in his own concerts, but actually bore

the expenses of its publication, so that it could reach as wide a public as possible” (The

Music of Liszt, 8).

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 199

kregor

gest that their collaboration extended well beyond the confines of the

Symphony: Realizing the work for piano challenged Liszt to extend

the possibilities of his technique, and marketing his transcription

prompted publishers to create music that mediated between the virtuosic concert stage and the amateur’s domestic sphere. In this view, Liszt

and his works constitute a virtual archive of contemporary artistic reception. Scrutinizing the Symphonie fantastique in conception, on stage,

and in print means harnessing the mechanisms of composition, spectacle, and technology, and the result approaches a more nuanced understanding of Liszt’s most emblematic piano transcription.

Realization and Collaboration

The transcription of the Symphonie fantastique came into being during one of the most remarkable periods of artistic growth in Liszt’s life

and one of the most unstable in Berlioz’s, and it continues to be considered a linchpin—a project that inspired, solidified, and sustained their

relationship during the 1830s and 1840s. Although ecstatic impressions

from concertgoers like Hallé have tended to craft a modern bias of

accomplishment in Liszt’s favor and downplay Berlioz’s role in its production, a broader view of the early history of the Symphonie fantastique

—not only the transcription but also the full score—reveals an almost

uninterrupted collaborative effort between the two artists. This high

level of investment in each other’s work hardly diminished when

Liszt published the Symphonie fantastique transcription in 1834, for his

arrangements of Berlioz’s orchestral pieces from the second half of the

1830s, particularly that of the Ouverture des francs-juges, bear the fingerprints of a symbiotic relationship. Each continued to support the other

with favorable reviews in an otherwise antagonistic French press, and by

the late 1830s their joint concerts had already become legendary, especially to their audiences east of Paris. Indeed, it was Liszt, riding high

on the heels of his own successes in Vienna and Pest, who finally persuaded Berlioz to undertake a German tour in the early 1840s. The

move, which was to take their careers in opposite directions, exacted a

heavy toll on their relationship. Efforts, sometimes spectacular, were

made on both sides to overlook the growing chasm between their artistic preferences, but Liszt and Berlioz never fully recovered the spirit of

artistic camaraderie they had so enjoyed in the 1830s.

Few stories make for better biographical reading than that of the

circumstances surrounding their first encounter. The 19-year-old pianist, in the wake of an aborted Symphonie révolutionnaire inspired by

the July Revolution and living in relative isolation in Paris, met the

brash Berlioz on the eve of the premiere of the latter’s controversial

199

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 200

the journal of musicology

200

new Symphonie fantastique. As Berlioz would recall years later in his Mémoires (chap. 31), the two spoke of Goethe’s Faust and immediately realized that they shared the same artistic predispositions. Liszt heard the

Symphony the next day and was so overcome by it that he dragged the

27-year-old French composer off to dinner for another round of discussion about literature, the arts, and the state of musical romanticism.

Of course, there was talk of the Symphony too, and Liszt succeeded

in convincing Berlioz that his new composition might profit from an

outsider’s sympathetic ear. Indeed, it is usually overlooked that the first

phase of their collaboration on the Symphonie fantastique seems to have

begun almost immediately after its 5 December 1830 premiere, with

the usually guarded Berlioz eagerly sharing his epic score with the pianist. His first surviving letter to Liszt vividly paints the enthusiasm that

both artists shared at the prospect of this artistic alliance: “I have not

been able to send you the score of my Symphony any sooner, for I am

forced to keep the ‘Bal’ scene, which I am now arranging for piano. I

am really afraid of abusing your time and kindness in asking you to

look at the other movements. Believe me, sir, that I am filled with gratitude over the support that you have already so readily wanted to give

me, along with the advice that you promise me—for me they are of inestimable value.”8 (By the next surviving letter, the two musicians are

already addressing each other with the personal “tu” form.)

If Berlioz arranged the second movement for piano toward the end

of 1830, it is no longer extant, but the idea held currency for at least

another two years.9 He did, however, re-work substantial portions of the

Symphonie fantastique while in Italy during his Prix de Rome tenure, and a

revised version was performed at the Conservatoire—again with an enthusiastic Liszt in the audience—on 9 December 1832 under FrançoisAntoine Habeneck’s baton.10 Although it has often been suggested that

8 C.G.I, 21 December 1830, p. 393. “Je n’ai pas pu envoyer plus tôt la partition de

ma symphonie, encore je suis obligé de garder la scène du Bal que j’arrange pour le piano. Je crains bien d’abuser de votre temps et de votre complaisance en vous priant de

vouloir bien les examiner; croyez, Monsieur, que je suis pénétré de reconnaissance pour

les encouragements que vous avez bien voulu me donner déjà, et pour les conseils que

vous me promettez; ils seront pour moi d’un prix inestimable.”

9 Letter of 19 January 1833 to Joseph d’Ortigue, in C.G.II, pp. 67–68. “Je n’ai pas

besoin de vous dire qu’il ne faut pas songer à arranger le bas [= le bal ] à quatre mains.” Incidentally, this purported arrangement of the second movement is not the fragment of

“Un bal” preserved in Berlioz’s hand located in the Musée Hector Berlioz at La CôteSaint-André. See Jérôme Dorival et al., eds., Catalogue des fonds musicaux conservés en Région

Rhône-Alpes: Les manuscrits (1600–1870) (Lyon: Ardim, 1998), 1:111.

10 The most detailed account of the (sometimes substantial) changes that Berlioz

made to his score between the 1830 and 1832 performances is D. Kern Holoman, The

Creative Process in the Autograph Musical Documents of Hector Berlioz, c. 1818–1840 (Ann Arbor:

UMI Research Press, 1980), esp. 262–82. Thomas Forrest Kelly provides a succinct

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 201

kregor

this concert prompted Liszt to transcribe the work, it was actually the

2 May 1833 performance in the Hôtel de L’Europe littéraire in Paris that

convinced him. (Significant for Liszt’s future performances of his transcription is the fact that only the second, third, and fourth movements

were mounted.) An excited Liszt wrote to Marie d’Agoult that “last

night I again heard . . . Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. Never has this

work appeared so complete, so true. If I am not dead by the end of

June, I will probably set it, arrange it for piano, regardless of whatever

pain and difficulty this enterprise will cost me. I am certain that you will

be more astonished by its reading than its execution.”11

Liszt’s final statement somewhat enigmatically conveys the novelties

of his transcription. He would write Adolphe Pictet in 1838 that he was

“the one who first proposed a new method of transcription in my piano

score of the Symphonie fantastique. I applied myself as scrupulously as if

I were translating a sacred text to transferring, not only the symphony’s

musical framework, but also its detailed effects and the multiplicity

of its instrumental and rhythmic combinations to the piano.”12 But

Liszt was being too modest. His intention, as the May 1833 letter makes

clear, was not merely to reproduce Berlioz’s music but to offer a nuanced recreation of a performance that brought together the originality of Berlioz’s composition with Liszt’s technical accomplishments. In

effect, the goal of the “reading” was to draw attention to the elements

that made Berlioz’s work so innovative by fusing notes with gestures. Liszt

absorbed Berlioz’s orchestral performance into his own technique, creating a matrix that operated on several distinct hermeneutic levels.

Example 1, from Liszt’s transcription of the slow introduction to the

first movement, begins around the middle of the transition back to the

“Estelle” theme.13 At measure 23, where the sustain pedal is noticeably

summary of Holoman’s findings as well as some new material in his First Nights: Five Musical Premieres (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), 226–35.

11 Liszt/d’Agoult, 3 May 1833, p. 57. “J’ai réentendu hier soir, à la soirée de l’Europe littéraire, la Symphonie fantastique de Berlioz; jamais cette œuvre ne m’avait paru

aussi complète, aussi vraie. Si je ne suis pas tué d’ici à la fin de Juin probablement je

me mettrai à l’œuvre, je l’arrangerai pour piano, quelque peine et difficulté qu’il y ait à

cette entreprise. Je suis persuadé que vous en serez encore plus étonnée à la lecture qu’à

l’exécution.”

12 Franz Liszt, An Artist’s Journey: Lettres d’un bachelier ès musique, 1835–1841, ed. and

trans. Charles Suttoni (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1989), 46–47.

13 All relevant examples are taken from Maurice Schlesinger’s 1834 print of the

Symphonie fantastique transcription (see Fig. 1). This edition is more germane to the following discussion, since many of the more characteristic performance markings do not

make their way into the 1877 revised edition and therefore the Neue Liszt Ausgabe (II/16).

For an examination of the editorial policies of the Neue Liszt Ausgabe as they affect the

critical edition of the Symphonie fantastique arrangement, see Jay Rosenblatt, review of

“Transkriptionen I: Transkriptionen der Werke von Hector Berlioz,” Notes 53 (1997):

1313–16.

201

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 202

the journal of musicology

example 1. Symphonie fantastique, “Rêveries, passions,” mm. 22–25,

Liszt arrangement

ritar

−

Š −− ‡

22

!

− ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ¦ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ

poco

Ý −− ‡

−

più

8va

!

!

forte

Š

Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł ¦Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł

¦ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ² ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ

Ł

−− ¦ Ł Ł ² Ł Ł ¦ Ł ¦ Ł ŁŁ ¦ Ł −Ł ŁŁ −Ł ¦ Ł −ŁŁ ¦¦ ŁŁ Ł

−

Ł ¦ Ł −Ł Ł

Š ¦ Ł Ł ²Ł Ł

Ł

len

ral

p

Slentan

− ¹

¹

Š − − ¦ ŁŁŁŁ

ŁŁŁ

−

Ł

Ł

¦

l

l

l

ben marcato il canto

ten

^[

n

Ł

24

Flute ð

−− − Oboi ð ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ ŁŁ

Š Clari l l l l l l

l l

n

^[

dolente

Sempre

l l l l l l l l

Basson Ł

Ł ŁŁ ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł ŁŁŁ Ł

ð

Ý −−

Ł Ł Ł

− n

Ł

Ł

Ł

^[ ~

n

Ł

25

ð

−− − ð ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ ^[ Ł ŁŁ ŁŁ

Š

nl l l l l l ^[ l l

l l l l l l l l

ŁŁð ŁŁ ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł Ł ŁŁ Ł

Ý −−

Ł Ł

Ł

− n

Ł

Ł

^[

~

23

202

do

loco

decres. molto

!

dan

Ł Ł ¦ Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł −Ł Ł ¦ Ł Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł −Ł Ł ¦ Ł Ł

Ł −Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł ¦ Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł

ŁŁ Ł Ł

Ł ² Ł ¦ ŁŁ

l l

ŁŁ ŁŁ

tan

do

do

¹

ŁŁl

ŁŁ

l

l

Ł

Ł Ł Ł

Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ

l l l

l l l

ŁŁ ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ

Ł

Ł ŁŁ

l

l

ŁŁ

ŁŁ

l

l

Ł

ŁŁl ŁŁl

ŁŁ

ŁŁ

l

l

ŁŁŁ

−¦ Ł ŁŁ

¦Ł

l

l

− ŁŁ

¦Ł

Ý

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 203

kregor

absent, the pianist is forced to contort the right hand into uncomfortable positions in order to maintain the integrity of the three voices. In

the next measure the winds enter with their main melody; and as the

texture thickens considerably, the demands on the pianist recede. Thus

the welcome arrival of a more subdued, settled theme at measure 24 is

reflected in Liszt’s arrangement by the analogous technical relief.

Liszt’s detailed setting of the work—neatly encapsulated under the concept of what he called a partition de piano —provides a visual component

to the action of Berlioz’s Symphony as it serves to guide the auditor and

highlight important formal junctures.

But there are also analytic elements etched into Liszt’s reading of

Berlioz’s score. His treatment of the idée fixe in the first three movements

provides one of the more noticeable examples. Schumann wrote that

this “principal motive to the Symphony is by itself neither pretty nor

suitable for contrapuntal treatment, but it improves more and more on

acquaintance through its later appearances.”14 Liszt encourages this acquaintance by fashioning accompaniments of the idée fixe (see Exs. 2a–c)

that begin to resemble one another over the course of the first three

movements. Much to the detriment of the pianist’s left hand, Liszt reduces Berlioz’s full score almost note for note in the first movement.

(The violent manner in which the pianist must execute the treacherous

downward leaps of m. 84ff creates an even clearer profile for the idée

fixe.) In the second movement, the shimmering tremolo accompaniment is routinely punctuated with left-hand leaps of a 10th or 11th—

that is, one octave more than Berlioz calls for in his score. Note here

that Liszt does not double both the A and F or E and C in measure 123

—it is the leaping figure that he wishes to highlight. This motive heralds the arrival of the idée fixe in the next movement at measure 87, and

it is the first sound heard in the left hand as each phrase of the beloved’s

melody emerges from its recitative-like state (see mm. 91 and 95). To be

sure, Berlioz provided the initial figurations for Liszt’s reading, but it

fell to the pianist to draw greater attention to their consistent profile. It

is little wonder, then, that his earliest mature works—for example the

first versions of the “Dante” Sonata or the “Vallée d’Obermann”—are

built on similar foundations of motivic unity.

These readings came rather quickly to Liszt, for he completed the

transcription in fewer than four months. The process was by no means

easy. On 30 August 1833, as Liszt was adding the finishing touches, he

entreated d’Agoult to “say three ‘Our Fathers’ and three ‘Hail Marys’

14 “Phantastische Symphonie,” NZfM 3/11 (7 August 1835): 43. “Das Hauptmotiv

zur Symphonie, an sich weder schön, noch zur contrapunctischen Arbeit geeignet,

gewinnt immer mehr surch die späteren Stellungen.”

203

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 204

the journal of musicology

example 2a. Symphonie fantastique, “Rêveries, passions,” mm. 72–86,

Liszt arrangement

][ espressivo con passione

Ł Łý Ł ð

Ł

Š ‡ ÐŁŁ

Ł ¼ ½

ð

72

!

݇ Ł ¼ ½

Ł

ÿ

78

!

Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł

ÝŁ Ł ¼ Ł Ł ¼

l l

l l

ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł

Ł

Ł

l l ¼ l l ¼

Š ð

²ð

^[

Ý

ÿ

83

204

!

Ł

ŁŁ

l

Ł

ŁŁ

l

ð

ð

Ł

Ł ¼

Ł

l

ð

ð

ÿ

ÿ

Ł ð

Ł

Ł

Łý

ÿ

ð

Ł

Ł ¼

Ł

l

ð

ÿ

¹ Ł Ð

¼ ¼

ð

4

ð

ÿ

ŠÐ

agitato sotto voce

ð

ð

ÿ

¦ð

ð

ÿ

ŁŁ

Ł

l

ÿ

ŁŁ

Ł ¼

l

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

ŁŁ

l

Ł

Ł ¼

Ł

l

example 2b. Symphonie fantastique, “Un bal,” mm. 120–24, Liszt

arrangement

²²

Š ² 4/

flute et hautbois

main gauche

molto espressivo

¦ Ł

120

!

Ý ²²² /

4

² ² ¦Ł

Š ² ¦Ł

Ł

¦ Ł Ł ŁŁ Ł

Ý ²²²

ÿ

les deux pedales

122

!

¦ Łý

¦¦ ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł

− ¦ ŁŁŁ ¦ Ł ŁŁŁ Ł ŁŁŁ Ł ŁŁŁ Ł ŁŁŁ Ł ŁŁŁ Ł

¦Ł

¦ ŁŁŁ

Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł

ÿ

n

Ł

¦ Ł ¦Ł

Ł

Ł Ł Ł

¹

Łl

\\\

lm

− ŁŁ

¦

−Ł

Ł

−Ł

Ł

p

¦ −− ŁŁŁ

−Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł

gardez toujours la pedale douce

¦ Łl

³ Łl

¦ Łl

³ ¹

~

¦ Łl

Łl

¦ ŁŁ ¦ Ł

Ł

³ ¦ Łl

¦ Łl

Ł

³

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 205

kregor

example 2c. Symphonie fantastique, “Scène aux champs,” mm. 90–95,

Liszt arrangement

!

flutes et hautbois

con carattere di recitativo

−Ł

Š − 42 ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł ý Ł Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł

\

Ý − 2 Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł ¹ ¼ý

4

\

90

ŁŁ Ł Ł

Ł Ł Ł

o

¹ ¹ ŁŁ Ło ³ Ł −Ł

[ marcatissimo

Ł Ł Ł Ł

¼ý

diminuendo

Š − −ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł ŁŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł

92

!

¦ Ło − Ło

¦ Ł −Ł

Łý

Ý − Łý

[[

~

Ło

Ł

Ło

Ł

Ło

Ł

Ło

Ł

Ło

Ł

Ło

Ł

decres

Š − −ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł Ł ŁŁ Ł Ł ŁŁ

\

93

!

¹

Ł¹

Ł

recitativo

Ý− Ł

Łu

−Ł

− Łu

Łý

Łý

Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł ¦¦ ŁŁ Ł

Ł Ł

Š − Łý

94

!

−Ło

−Ł

Ý−

ÿ

¹

Ł

Ł

\

Ł

−Ł

Ł Łp Ł

Ł

−Ł

Ł ÝŁ

[

p

Ł

ý

Ł

¹ ¹ ŁŁ Ł ¾ Ł Ł ý

[ marcatissimo[[ ~

Ł

Ł

¹

ŁŁŁŁŁŁ

Ł Ł Ł

Ło Ło Ło

Ł Ł Ł

for its benefit.”15 Her prayers must have been answered, for on the

same day Berlioz wrote to Humbert Ferrand that “Liszt has just arranged

15 Liszt/d’Agoult, 30 August 1833, p. 84. “La Symphonie fantastique sera terminée

dimanche soir; dites trois Pater et trois Ave en son intention.”

205

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 206

the journal of musicology

206

my symphony for piano—it is astonishing.”16 But Berlioz was still reporting on the novelty of the transcription to Ferrand almost two months

later, writing that “Liszt has just reduced my entire Symphonie for piano”

and that it will soon be engraved.17

Berlioz’s repetitious comments suggest either that Liszt did not

complete all five movements of the transcription by the end of August

1833 or that he revised them in September and October. (No autograph manuscript of any portion of the transcription before the 1860s

has been located.) Perhaps the thought of publishing the work necessitated a thorough revision, but Liszt just as easily may have been readying the transcription for its private premiere in d’Agoult’s salon. In her

Mémoires she recalls that “at my places in both Paris and in the countryside, the 1833–1834 season offered good music. New compositions of

the musical Romanticism were played, [including] Berlioz’s Symphonie

fantastique arranged for the piano by Liszt.”18 Introducing demanding

new works in an intimate venue was not unique for Liszt, who preferred

throughout his concert years to premiere works by his contemporaries

outside the concert hall. For example, in 1839 he wrote to Robert Schumann of his enthusiasm for playing Carnaval, the Davidsbündlertänze, and

the Kinderscenen for the Viennese public yet was reluctant to introduce

the Kreisleriana and the Fantasy in C. In Liszt’s eyes, the former were readily accessible to an audience, whereas the latter were “more difficult for

the public to digest—I shall save them for later.”19 Liszt’s performance

of the Fantasy, for example, likely took place behind closed doors during his visit to Leipzig in 1840.

With a successful private premiere already behind it, the transcription of the Symphonie fantastique was engraved by May 1834 at the latest.

Both Liszt and Berlioz checked the proofs, a process that initially did

not seem to pose many difficulties. Liszt, whose concert activities before

late 1834 were sporadic, hoped to precede his arrival on the public stage

with a spectacular showing in the marketplace. He relates to d’Agoult

16 C.G.II, 30 August 1833, p. 113. “Liszt vient d’arranger ma symphonie pour le

piano; c’est étonnant.”

17 C.G.II, 25 October 1833, p. 128. “Liszt vient de réduire pour le piano seul la

Symphonie entière.”

18 Marie d’Agoult/Daniel Stern, Mémoires, souvenirs et journaux de la Comtesse d’Agoult

(Daniel Stern), ed. Charles F. Dupêchez (Paris: Mercure de France, 1990), 1:264. “Pendant

une saison, . . . [on] faisait aussi chez moi, à Paris et à la campagne, de bonne musique;

on y jouait les compositions nouvelles du romantisme musical: La Symphonie fantastique de

Berlioz, arrangée pour le piano par Liszt.” Dupêchez bases the date of this season on unpublished letters by d’Agoult from August and September 1833 (see pp. 413–14).

19 Letter of 5 June 1839 in Franz Liszt, Briefe, ed. La Mara (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1893–1905), 1:27. “En attendant je compte jouer en public votre Carnaval, quelquesuns des Davidsbündlertänze et des Kinderscenen. Le Kreisleriana et la Fantaisie qui m’est

dédiée, sont de digestion plus difficile pour le public—je les réserverai pour plus tard.”

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 207

kregor

that “I will not write anything for a month, as a number of corrections

here have to be taken care of. By the beginning of winter I shall have

seven or eight pieces engraved.”20 The transcription, in fact, was to be

his magnum opus, the apotheosis of a half-decade of self-regulated

study of the masters: Liszt proudly informed his student Valérie Boissier

of its imminent arrival in mid summer 1834 that “in two weeks I shall

have the honor of sending you the first copy of the Symphonie fantastique.

With it you will then have a collection of rather large things.”21

Rumors of a transcription of Berlioz’s Symphony by Liszt reached

Germany around the time of his letter to Boissier. An anonymous “Brief

aus Paris” informed readers of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik that “the

most amazing difficulties are but child’s play to Liszt. He sight-reads

everything, dexterously and instantly, with such an artifice and perfection that anyone else might only be able to pick out were he to spend

endless hours practicing. The reader can glean an idea of his playing

by procuring his four-hand arrangement of a symphony by Berlioz that

will appear shortly at [Maurice] Schlesinger’s.”22 The source of this

Liszt/d’Agoult, 1 May 1834, p. 128. “Je n’écrirai point avant un mois–il me faudra faire une quantité de corrections d’ici là au commencement de l’hiver j’aurai 7 à 8

Œuvres de gravées.” Berlioz explains to Ferrand around the middle of the month (C.G.II,

p. 184) that “the Symphony has been engraved and we are correcting the proofs, but it

will not appear until Liszt returns from Normandy, where he will spend four or five

weeks” (“La Symphonie est gravée nous corrigeons les épreuves, mais elle ne paraîtra pas

avant le retour de Liszt, qui vient de partir pour la Normandie, où il passera quatre ou

cinq semaines”).

21 Letter of June 1834 in Robert Bory, “Diverses lettres inédites de Liszt,” Schweizerisches Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft 3 (1928): 64. “J’aurai l’honneur de vous envoyer le

Ier exemplaire de la Symphonie fantastique dans une quinzaine; puis, vous aurez successivement une quantité d’assez grosses choses.” Bory suggested the date of this letter as “Spring

1834,” but Adrian Williams (ed. and trans., Franz Liszt: Selected Letters [Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1998], 28–29) has been able to narrow the date down to late June or early July

1834.

22 NZfM 1/18 (2 June 1834): 72. “Ihm [Liszt] sind die tollsten Schwierigkeiten

Kinderspiele, er spielt vom Blatt Alles sogleich ganz fertig, mit allen Künsten, mit allen

Vollkommenheiten, die er [sic; should probably read “ein Anderer”] nach langem Ueben

desselben Stücks nur würde herausklauben können. Sie werden eine ungefähre Idee von

seinem Spiel erlangen, wenn Sie eine Symphonie von Berlioz, die er vierhändig arrangirt

hat, und die binnen kurzem bei Schlesinger hier erscheinen wird, zu Gesicht bekommen

werden.” It is possible that the author is Heinrich Panofka, the Parisian-based music

teacher and critic who worked for the Gazette et revue musicale, acted as a correspondent

for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, and was a strong supporter of Berlioz’s.

It is understandable that the correspondent assumes a four-hand transcription,

which was by far the most popular keyboard medium during the 19th century. See Helmut Loos, Zur Klavierübertragung von Werken für und mit Orchester des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts (Munich and Salzburg: Emil Katzbichler, 1983), 8; and Thomas Christensen, “FourHand Piano Transcription and Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Musical Reception,”

Journal of the American Musicological Society 52 (1999): 258–89. Given this musical climate,

Liszt’s solo transcription of Berlioz’s First Symphony becomes all the more unusual.

20

207

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 208

the journal of musicology

208

report is unclear, and though it is dubious in several respects (how can

one get a sense of Liszt’s technique by playing through a four-hand

transcription?), it nevertheless represents the first mention of the work

outside private correspondence.

More important is the way in which the author here appropriates

the Symphonie fantastique transcription to frame Liszt’s celebrated technique. Indeed, the report seems to corroborate Liszt’s statement that his

Berlioz arrangement defines him better musically than any other work

he has thus far produced. Schumann agreed, and like the anonymous

Parisian correspondent similarly highlighted the educational benefits

that Liszt’s transcription could provide aspiring pianists. “Liszt,” he

wrote toward the end of his long review, “has applied so much industry,

enthusiasm, and genius that the result, like an original work summarizing his profound studies, must be considered as a practical method of

instruction in playing a score at the piano.”23 Schumann’s formulation,

of course, precisely sums up the most important elements of a successful musical reproduction, but since Schumann had never seen Liszt or

Berlioz, he could not appreciate just how skillfully Liszt’s piano score

recreated the dynamics of performance. Instead, the symphonic ambition of Liszt’s arrangement offered Schumann new solutions to his

own works, as Carnaval, the Etudes symphoniques, and the Piano Sonata,

op. 11, were all in progress by the summer of 1834. And Schumann’s

great Fantasy in C major, which appeared in April 1839 with a dedication to Liszt, takes the symphonic ambition of the Symphonie fantastique

arrangement to one of its most refined levels. For example, a likely

model for measures 35–41 from the second movement of Schumann’s

work—which requires hand crossing, demands crisp articulation, and

registrally expands from out to in and then back out (> <)—can be

found in the fourth movement, measures 49–59, of Liszt’s partition de

piano. Indeed, it possesses many of the same elements, the only difference being that the contour is opposite: going from closed to open and

back to closed position (< >).24

23 Translation modified from Berlioz, Fantastic Symphony, ed. Cone, 244. The original (NZfM 3/12 [11 August 1835]: 47) reads: “Liszt hat [den Clavierauszug] mit so viel

Fleiß, Begeisterung und Genie ausgearbeitet, daß er wie ein Originalwerk, ein Resümee

seiner tiefen Studien, als praktische Clavierschule im Partiturspiel angesehen werden

muß.”

24 Theo Hirsbrunner has documented several textural parallels between Schumann’s Fantasy and Liszt’s arrangement, suggesting that “doch kennt er [Schumann]

auch subtilere Töne, die aber wieder wie die Übertragung aus einem Orchesterstück anmuten” (Hirsbrunner, “Schumann und Berlioz,” in Hector Berlioz: Ein Franzose in Deutschland, eds. Matthias Brzoska, Hermann Hofer, and Nicole K. Strohmann [Laaber: LaaberVerlag, 2005], 56.). Indeed, Hirsbrunner would have found even more parallels between

the two works had he made use of the Schlesinger print from 1834 rather than drawing

upon examples found in the Neue Liszt Ausgabe or the revised 1877 print.

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 209

kregor

Liszt’s arrangement would have been available to Schumann toward

the end of November, for its publisher Maurice Schlesinger advertised

the work for the first time in his Gazette musicale de Paris on 9 November

1834.25 A week earlier, Schlesinger had announced an upcoming concert by Berlioz that would feature a version of the Symphonie fantastique

to which “M. Berlioz has added several new orchestral effects to his

work that noticeably increase its brilliance.”26 This type of multifaceted

advertising campaign was typical for the business-savvy Schlesinger, and

for much of the following decade the fate of the printed work would be

closely allied with that of the performed work.

* * *

This unusually close relationship on stage and in print was hardly

spontaneous. From conception to publication, the early course of the

Symphonie fantastique transcription had been navigated by both Berlioz

and Liszt. The correspondence of the two composers harbors many details that shed further light on the intricacies of the work’s genesis. Liszt

reviewed Berlioz’s full score shortly after the work’s premiere, perhaps

even offering advice to Berlioz as to how it might be improved. And

while there is no evidence to suggest that Berlioz incorporated Liszt’s

recommendations (whatever they may have been) into later versions of

his work, Berlioz does note in his Mémoires (chap. 31) that the third

movement made no impression on his audience at the premiere and

that he resolved to rewrite it immediately.

Berlioz was still modifying the full score when Liszt began transcribing the work in May 1833, and would continue to do so for the next

decade. Indeed, it is often overlooked that Liszt’s arrangement bears

witness to a version of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique that no longer

exists, or at least is no longer performed with any regularity. Berlioz’s

25 See the Gazette musicale de Paris 1/45 (9 November 1834): 364, where the work is

listed as “Musique nouvelle, | Publiée par Maurice Schlesinger. | Épisode de la Vie d’un

Artiste, | Simphonie fantastique en cinq parties, par Berlioz, arrangée | pour le piano par

| LISZT. | Prix net 20 fr.” Berlioz writes to Humbert Ferrand on 30 November 1834

(C.G.II, p. 208) that “the Symphonie fantastique has appeared, but since Liszt has

invested a huge amount of money in its publication, we, along with Schlesinger, have

decided not to allow a single copy to be given away” (“La Symphonie Fantastique a paru;

mais, comme ce pauvre Liszt a dépensé horriblement d’argent pour cette publication,

nous sommes convenus avec Schlesinger de ne pas consentir à ce qu’il donne un seul

exemplaire.”). Indeed, it seems that Liszt’s partition was not released until the end of

the month, for an announcement in the Gazette musicale de Paris on 30 November

(p. 388) states that “La grande symphonie fantastique de Hector Berlioz en partition de

piano, arrangée par Liszt, vient de paraître. Nous rendrons compte de cette importante

publication.”

26 “Nouvelles,” Gazette musicale de Paris 1/44 (2 November 1834): 356. “M. Berlioz a

ajouté à son ouvrage plusiers effets d’orchestre nouveaux qui en augmenteront sensiblement l’éclat.”

209

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 210

the journal of musicology

210

initial programs for the second movement, for instance, explained that

“The artist finds himself in the most varied of life’s situations—at the

center of a rousing party, in the peaceful contemplation of nature’s

beauties; but everywhere—in town, in the country—the dear image appears before him, throwing his mind into a troubled state.”27 Indeed,

the first appearance of the idée fixe in the second movement of Liszt’s

arrangement (Ex. 3)28—the beloved’s apparition to the artist among a

sea of partygoers—is a striking tableau of the protagonist’s mental condition. The beloved’s theme maintains the regular three count of the

nearby waltz, but the accompaniment operates in spasmodic two-beat

pulses. This hocket effect is further distinguished by a sudden reduction in the orchestral scoring, with the accompaniment given over to a

handful of plaintive strings that snake throughout the upper registers.

Thus with all musical action coming to a grinding halt, the awkwardness of the artist’s situation becomes the focal point of the movement.

Berlioz smoothed over the jarring lines of this scene when he carried

out one of his many revisions sometime after 1834, replacing the metrical dissonances with fragments of the waltz motive in the strings. And

he would eventually reduce the psychological impact of this musical

event by similarly streamlining the plot of the entire movement: “[The

artist] encounters the loved one at a dance,” Berlioz now envisions,

“in the midst of the tumult of a brilliant party.”29 (The pianist Idil Biret,

in what is one of the earliest recordings of Liszt’s transcription committed to compact disc, incorporates Berlioz’s later revisions of these measures into her interpretation, creating a product that does not correspond to any published version.)30

D. Kern Holoman, in his study of Berlioz’s autograph manuscripts,

notes that Liszt’s piano score diverges from Berlioz’s published orchestral score in several minor spots as well. Berlioz, Holoman opines, may

have been inspired by some of the solutions Liszt put forth in his

27 As it reads in the program included with Liszt’s arrangement: “L’artiste est placé

dans les circonstances de la vie les plus diverses; au milieu du tumulte d’une fête, dans la

paisible contemplation des beautés de la nature; mais partout, à la ville, aux champs, l’image chérie vient se présenter à lui et jeter le trouble dans son âme.”

28 The full score of this passage is included in Hector Berlioz, Symphonie fantastique

(vol. 16 of Hector Berlioz: New Edition of the Complete Works), ed. Nicholas Temperley (Kassel:

Bärenreiter, 1972), 198.

29 As it reads in the program included in Berlioz, Fantastic Symphony, ed. Cone, 32–

33. “Il retrouve l’aimée dans un bal au milieu du tumulte d’une fête brillante.”

30 See Franz Liszt, Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique (Piano Transcription), Idil Biret, piano

(Naxos 8.550725 [1992]), track 2, 205–227. Biret is perhaps the first modern pianist

to have performed Liszt’s transcription in its entirety. See her recording of the work, Symphonie Fantastique. Solo Piano Version by Franz Liszt (Finnadar SR 9023 [1979]). Leslie

Howard’s recording of the same composition (Hyperion CDA66433 [1991]) preserves a

reading very close to that of the new Liszt critical edition.

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 211

kregor

example 3. Symphonie fantastique, “Un bal,” mm. 131–46, Liszt

arrangement

²²

Š ² 4/ ¦ ŁŁ ¦ Ł

131

!

!

!

molto pronunziato

il canto

Ý ²²² / ¾ ý

4

²²

Š ²

136

¦Ł

¦Ł

Ł

¹

¦ Ł ¦ Łl

Ł

Ł

¾

¾ ¹

n

¦ ŁŁ ¦ ¦ ŁŁ Ł

sempre

~

~

141

ŁŁ

²²² ¦¦ ŁŁ −− ŁŁ −− ŁŁ

Ł

Š

²² n

Š ² −−ŁŁ

cres

²²

Š ²

²Ł Ł

cen

¾

¦Ł

¦Ł

−Ł

Ł

¹ ¹Š

¾ −Ł ¦ Ł ¾

~

\\ lamentoso ¦Ł

²Ł

Ł

Ł

^[

Ł ¦ Ł

Ł ¦Ł

¦ Ł Ł

Ł ¦Ł

Ł

¾

−Ł

¦Ł

Ł

¦Ł

¾

~ ~ − Ł Ł

−Ł Ł

¦Ł ¦Ł

¦Ł

¦Ł

perdendendo

Ł

¾

−Ł ¦ Ł

¾

²Ł ¦Ł

Ł ¦Ł

¾ ¹

poco

Ł ²Ł

~ ¾

¦Ł Ł

n

¦ Ł ¦ Ł

¾ ¦Ł ¦Ł

a

¾ ¦Ł

²Ł

¾ ¹ ¦ ŁŁ

cantando

¦ Ł

¦Ł

poco

¾ ¦Ł

Ł

~ ~ ¾

¾

dolce

sospirando

²Ł

²Ł

−Ł

Ł

n

¾ ²Ł

−Ł −Ł

Ł Ł ¹

~ ~ ~

n

Ł − Łn − ŁŁ ŁŁ − Ł ¦ Ł ¦ Ł Ł

Ł

¦Ł

Ł Ł ¦ Ł ¦ ŁŁ

Ł Ł −Ł

do

Ł ²Ł

Ł ²Ł

Ł

Ł

−Ł Ł

Ł ²Ł

~

¦Ł

¾

¦ Ł

¾ ¦ Ł

¾ ¹

arrangement when Berlioz revised his orchestral score sometime in the

later 1830s. Most notable is the first occurrence in Liszt’s edition of

the “consolations religieuses” in the accompanying program at the end

of the first movement, the musical analogue of which coincidentally

lends itself well to piano reduction.31 But although Holoman suggests

that the addition was probably incorporated at the last minute, the first

edition issued by Maurice Schlesinger in November 1834—which was

subsequently reprinted in 1836 with only cosmetic changes to the music

—gives no indication that this passage was engraved hastily.32

Holoman, The Creative Process, 275–76.

The coda begins on the fourth system of page 22 of Schlesinger’s edition. If

Schlesinger had added the section at the last minute, either the preceding pages would

be excessively cramped or the final page of the movement would be unusually bare.

Thomas Forrest Kelly believes that the addition took place at the very beginning of December 1830, perhaps only a day or two before the work’s premiere. See First Nights, 227.

31

32

211

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 212

the journal of musicology

212

Quite the opposite, in fact. Liszt and Berlioz actually spent about as

much time correcting proofs—at least three months—as Liszt did in

making his initial transcription of the entire work. The crestfallen pianist reports to Marie d’Agoult in July 1834 that “the fourth proof

[Liszt’s emphasis] of Berlioz’s Symphony is giving me a headache. It really is a terrible undertaking.”33 That Schlesinger, who was notorious

for running a tight ship with his journal and musical offerings in the

1830s, would acquiesce to such delays is surprising. Indeed, the timeline suggests that changes from proof to proof were more than merely

cosmetic. Although the type of collaboration demonstrated by Liszt and

Berlioz is rare in music-making from this period, the art historian

Stephen Bann reminds us that it is was ubiquitous in the world of the

visual arts. Painters and printmakers, including the Parisian engraver

Luigi Calamatta, whom Liszt knew intimately, often worked side by side

in the same studio, particularly when it came to applying the finishing

touches: Bann writes that “These painters (no doubt in varying degrees)

adapted to considering their works in the light of their possible reproduction, and, at the same time, in the light of the practical arrangements for their marketing.”34

Two heads were of course better than one for catching slips of the

pen and working out last-minute compositional problems, but this

collaboration yielded more substantial dividends as well. The care with

which Liszt and Berlioz prepared the piano score of the Symphonie fantastique is also evident in Liszt’s piano solo arrangements of Berlioz’s

Ouverture des francs-juges and Ouverture du roi Lear, both of which date

from the second half of the 1830s.35 Liszt’s esteem for Berlioz had

hardly abated when Joseph d’Ortigue’s biography of the pianist appeared in 1835 in the pages of Maurice Schlesinger’s Gazette musicale de

33 Liszt/d’Agoult, 7 July 1834, p. 161. “J’ai la tête cassée de la 4me épreuve de la

Symph[onie] Berlioz. Décidément c’est une chose monstrueuse.”

34 Stephen Bann, Parallel Lines: Printmakers, Painters and Photographers in NineteenthCentury France (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2001), 6.

35 The sources are imprecise regarding the dating of these overtures. When Lina

Ramann (Lisztiana: Erinnerungen an Franz Liszt in Tagebuchblättern, Briefen und Dokumenten

aus den Jahren 1873–1886/87, ed. Arthur Seidl, rev. Friedrich Schnapp [Mainz: Schott,

1983], 403) questioned Liszt about the dates of their creation in a December 1875

Fragezettel, he responded that they both came about “during my Swiss trip, [18]35.” However, Berlioz writes Liszt (C.G.II, p. 282) on 25 January 1836 that “Je ne sais comment

t’envoyer les deux partitions que tu me demandes.” A couple of months later Liszt requests his mother to “Demander à Berlioz de ma part de vous remettre la Partition de la

Symphonie d’Harold et de son Ouverture du roi Lear,” suggesting that at least one of the overtures had yet to be arranged (see Franz Liszt, Briefwechsel mit seiner Mutter, ed. Klára Hamburger [Eisenstadt: Burgenländische Landesregierung, 2000], 99). Indeed, Berlioz requests of Liszt (C.G.II, p. 348) on 22 May 1837 that “Si tu en as le temps, arrange donc

l’ouverture du Roi Lear.”

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 213

kregor

Paris. D’Ortigue, whom Liszt supplied with numerous personal anecdotes and information found nowhere else, wrote that Berlioz was a

vision for the pianist, a figure whose influence by far eclipsed that of

Chopin or Mendelssohn.36 Liszt continued to demonstrate admiration

for his older colleague by publishing his arrangement of the Francsjuges overture in 1845, and a heretofore unknown fragment of an autograph from about 1837 suggests that the arrangement went through

multiple iterations in the 1830s.37 The music of this earlier version (see

Ex. 4) is fully written out, complete with ossia (not reproduced here),

and it diverges in several places from the published edition, most notably

by the inclusion of the “piano” direction at measure 118 and a different

reading of the inner voice at measure 129. To be sure, differences between fragment and print are slight, but the fragment’s reading better

reflects that of Berlioz’s full score, which had been published in 1836.

Liszt may have decided to revise these measures for the sake of clarity:

The frequent hand crossing in this reading can make for a clumsy performance, particularly if the pianist hopes to achieve a rendering even

remotely close to Berlioz’s astonishingly fast tempo direction of = 80.

Like his arrangement of the Symphonie fantastique, Liszt’s Ouverture

du roi Lear fixes a reading of Berlioz’s work that is no longer performed

today. Although there is less documentary evidence, it is reasonable to

assume that the process of its creation unfolded in a manner similar to

that of the Symphonie fantastique. Liszt completed his arrangement by

February 1838 at the latest, and Berlioz continued to revise his orchestral score until the publication of the parts in 1839.38 (Liszt’s arrangement remained unpublished until 1987.)39 And as he had with the

arrangement of the Symphonie fantastique, Berlioz kept close tabs on

36 Joseph d’Ortigue, “Études biographiques. I. Franz Listz [sic],” Gazette musicale de

Paris 2/24 (14 June 1835): 202. “C’est dans le même esprit qu’il étudie les qualités distinctives des jeunes artistes ses amis: Chopin, Hiller, Mendelshon, Dessauer, Urhan,

V. Alkan, Berlioz qui a été pour lui une apparition.”

37 This fragment appears to be the only holograph of Liszt’s Ouverture des Francsjuges arrangement and is found on the underside of a collette on p. 16, systems 2–3 of

D-WRgs, GSA 60/U 57, Liszt’s arrangement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony (first version). The paper of the collette matches that of U 57 (see Rena Charnin Mueller, “Liszt’s

‘Tasso’ Sketchbook: Studies in Sources and Revisions” [Ph.D. diss., New York Univ.,

1986], 366; and Jay Michael Rosenblatt, “The Concerto as Crucible: Franz Liszt’s Early

Works for Piano and Orchestra” [Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Chicago, 1995], 452). The terminus

ad quem of the work and the fragment must be 1840, the year in which Liszt published his

Beethoven Seventh arrangement with Tobias Haslinger in Vienna.

38 See Berlioz’s letter of 8 February 1838 to Liszt in C.G.II, 412.

39 The first edition of this transcription does not evaluate the compositional phases

evident in the autograph manuscript. See Hector Berlioz, Overture to King Lear. Transcription for Pianoforte Solo by F. Liszt, ed. Ken Souter (London: Liszt Society Publications,

1987).

213

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 214

the journal of musicology

example 4. Ouverture des francs-juges, earlier version of mm. 116–34,

Liszt arrangement. Underside of collette on D-WRgs, GSA

60/U 57, p. 161

½

ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁ

−

Š − −− 116

!

Łý

−−− ŁŁ ýý Ł Ł ý ŁŁ

−

Š

ŁŁ ð

Ł

Ý −− − Ł ð Ł Ł

Ł

− Ł

121

!

214

− Ð

Š − −− Ð ðð ŁŁ

¼

Ł

Ý −− − Ł ¼ ŁŁ ¼

−

126

!

Ð

Ð ð Ł

ð Ł

ðð l ŁŁ ŁŁ

Łl ¼ ŁŁ ¼ Ł ¼ Ł ¼

Ł

Ł Ł

senza

½

ŁŁŁ ððð

ŁŁ ðð ŁŁ ŁŁ ¼

][

piano

Ý −− − l ¼ Łl ¼ Łl m.g.ðð Łl ŁŁ l ¼ Łl ¼

− Ł

Ł

Ł Ł

Ł Ł

Ł Ł

ð ð

ð ðð ð ŁŁ Ł¼Ł ¹ ŁŁ ŁŁ ýý Ł

¼

ð

Ł

Ł ð Ł Ł

Ł

Ł ¼ Ł ¼ Ł ¼ Ł ¼

Ł

¼ ¹ Ł Ł ý Ł ÐÐ

ý

Ł

ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł

¼ ðð Ł

ð

Ł ðð Ł ŁŁŁ

Ł ¼ Ł ¼

Ł ¼ Ł

Ł Ł

agitazione

Ð

Ð

Łý Ł Łý Ł

Łý Ł Łý Ł

ðð ŁŁ ŁŁ ŁŁ Ł

Ł

Ł ¼ Ł ¼ Ł ýý ð ŁŁ ŁŁ ýý Ł Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł ý Ł

ð

ŁŁ ý Ł Ł ýý ŁŁ ðð ðð ð ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

ð Ł Ł

Ł ¼ Ł ¼ Ł ¼ Ł ¼

Ł

Ł Ł

Łý Ð

ðý

− ¼

ŁŁ

Š − −− ŁŁ ¹ ŁŁ ŁŁ ýý ŁŁ Ð ððð ŁŁŁ ŁŁŁŁ ý ŁŁ ŁŁ ýý ŁŁ ð ý ððð

ŁŁ

¼

¼

ðð

ŁŁ

Ł

ðð

Ł

Ł

Ý −− − Ł ð Ł Ł

Ł ¼

Ł Ł

¼

Ł

− Ł ¼ Ł ¼

Ł ¼ Ł ¼

Ł

Ł

¼ Ł ¼

Ł

Ł

131

!

dolce e legato

ð

ð

1

The E at m. 123, r.h., has been crossed out by Liszt.

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 215

kregor

example 5. Ouverture des roi Lear, earlier version of mm. 164–68, Liszt

arrangement. Below collette on D-WRgs, GSA 60/U 43,

p. 102

[

ð

Š Łðð Ł Ł Ł Ł

164

[ Ý]

]

−Ð

ðý

ð

²Ł

Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł − Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł Ł ² Ł Ł

ðð

rit

² ÐÐ

Ð

[]

¼

ð

²Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²Ł Ł Ł Ł

Š

167

Ý

[ ]

Ł Ł Ł ŁŁŁ Ł

ŁŁ Ł ŁŁ Ł Ł Ł ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

ŁŁŁ

2 Bracketed portions are unreadable (due to the wax) and have been extrapolated

based on surrounding material.

Liszt’s work, offering suggestions for improving the reading of the coda

as late as 1853.40

The autograph of the Roi Lear overture, housed in the Goethe- und

Schiller-Archiv in Weimar, resembles the Francs-juges overture in revealing several layers of revisions. Among the numerous changes in the

manuscript, one of the most interesting is an early reading of measures

164–68 (see Ex. 5).41 This passage radically shifts the balance of the

entire work and is particularly noticeable in performance. With its alternation of thumbs to provide momentum in the inner voice, the passage visually parallels those of measure 275ff and 402ff, and all three

passages can be heard as transitional sections: Measures 164–68 begin

the buildup of tension that is released with the more lyrical theme at

measures 179ff; measures 275ff grow in force until the recapitulation at

measure 305; and measures 402ff lead into the march-like theme at

40 In his letter of April 1853 to Liszt (C.G.IV, pp. 314–15), Berlioz disagreed with

the pianist’s decision to substitute three triplet quarter notes for Berlioz’s four eighth

notes.

41 This reading is covered by a collette on page 10, staves 1–2 of D-WRgs, GSA 60/

U 43. Beginning at m. 617, Liszt’s arrangement also contains a substantially different

ending than Berlioz’s published full score. N.B.: All measure numbers refer to Liszt’s

arrangement, which deviates from Berlioz’s score by one measure beginning at m. 85.

215

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 216

the journal of musicology

216

measure 412. Liszt had written in 1836, the very period in which he was

arranging Berlioz’s overtures and Harold Symphony, that “genius is the

majesty of the new, the spirit creating its own form, the feeling of the

infinite manifesting itself in the finite. Now, in which musical works do

we find a higher level of innovative daring, depth of thought, and richness of forms than in Harold and the Episode de la vie d’un artiste?”42 Liszt

made an equally strong case for Berlioz’s musical radicalism in his transcriptions: By reinforcing Berlioz’s formal structures through additional

transitional figures such as those found in the Ouverture du roi Lear

(and, as we shall see, the Symphonie fantastique), Liszt was merely giving

evidence in music for what he had suggested in print.

Even before he had completed his first batch of transcriptions,

Liszt began seeking out a publisher. In December 1837 he contacted

Berlioz with an offer: “If your intention is to publish [my arrangement

of Harold en Italie] and the two overtures, [Friedrich] Hofmeister in

Leipzig is paying me six francs per page for everything I send him. That

would amount to about six hundred francs.”43 After failing to secure a

publisher in Paris, Berlioz told Liszt to “do the negotiations yourself—I

know you have my best interests at heart.”44 Although the publishing

venture ultimately fell through, the close collaboration that the two

artists had shared in private would frequently spill out onto the concert

stage beginning in the second half of the 1830s and continuing well

into the next decade. The Symphonie fantastique, however, would play

only a marginal role.

42 Franz Liszt, Frühe Schriften, ed. Rainer Kleinertz (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel,

2000), 332. “Le génie, c’est la grandeur dans la nouveauté; le génie, c’est la pensée, se

créant sa forme; c’est le sentiment de l’infini se manifestant dans le fini. Or, dans quelles

œuvres musicales trouverons-nous à un plus haut degré la hardiesse de l’innovation, la

profondeur de la pensée et la richesse de formes que dans Harold et l’Episode de la vie d’un

artiste?” The original article, ostensibly written as a review of Berlioz’s 4 December 1836

concert in Paris, was first published as “Concert de M. Berlioz,” in Le Monde on 11 December 1836.

43 Letter of December 1837 from Liszt to Berlioz in C.G.II, pp. 387–88. “Tu recevras d’ici à peu l’arrangement de piano de ta seconde symphonie. Si ton intention était

de la livrer au public (ainsi que les ouvertures des Francs-Juges et du Roi Lear), Hoffmeister

à Leipzig, me paye 6 francs par page pour tout ce que je lui envoie. Ce serait par conséquent environ 600 francs.” In fact, Liszt had been in contact with several publishers, including Hofmeister, in an attempt to publish his own original compositions. See Liszt’s

letter to Ignaz Moscheles of 28 December 1837 in Hans Rudolf Jung, ed., Franz Liszt in

seinen Briefen: eine Auswahl (Berlin: Henschelverg Kunst und Gesellschaft, 1987), 64–66.

44 Letter of 8 February 1838 from Berlioz to Liszt in C.G.II, p. 412. “J’ai parlé à

Richault de la gravure de mes deux ouvertures que tu as réduites pour le piano, il ne s’en

soucie pas; pour la symphonie, si Hoffmeister veut m’en donner un prix raisonnable je

ne demande pas mieux que de la lui laisser publier, ainsi que les deux autres manuscrits

que tu m’as envoyés; fais la négociation toit-même, je te confie mes intérêts absolument.”

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 217

kregor

Content and Reaction

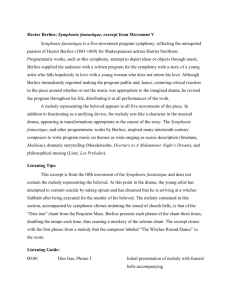

Over the next 45 years, Liszt created two arrangements of the

complete Symphonie fantastique for piano solo as well as an independent

arrangement of the “Marche au supplice” (see Fig. 1). Alongside this

enterprise he reduced sections of Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini and La

Damnation de Faust, continued to tinker with his early arrangements of

Berlioz’s two overtures, and diligently—if sporadically—worked to perfect his reduction of the Harold Symphony for viola solo and piano.45

(Liszt apparently also transcribed the Carnaval romain overture, but it

was not published and the manuscript is no longer extant.) Many of

these later arrangements were carried out during the final years of

Liszt’s tenure at Weimar, and thus their raison d’être is far removed from

the intense period of creativity and camaraderie that took place between the two composers in the aftermath of the July Revolution.

Perhaps the biggest transformation to come over Liszt between

these two phases of involvement with Berlioz’s music had less to do with

composition and almost everything to do with performance. Indeed,

sandwiched between the early 1830s and the 1850s was Liszt’s Virtuosenzeit, the years in which Liszt rose to become Europe’s top pianist and

showman. He began his concert career in earnest almost immediately

after putting the finishing touches on the Symphonie fantastique transcription, emerging in late 1834 from the relative isolation—and safety

—of salon entertainments to enter the public performing world in

force. To be sure, Liszt had given concerts to large audiences prior to

1834, but the frequency of his appearances and the virtuosity of his

offerings increased dramatically. For some time, as he famously related

to Pierre Wolff, he had “been working his mind and fingers like two

wayward spirits,” and he wanted to demonstrate to the world just how

far he had come as both savant and musician.46 By 1838 he had been

able to catapult himself onto the European main stage with relative

ease, and he maintained his preeminence over a sea of instrumental

and vocal virtuosos for a decade.

But the effects of “Lisztomania,” as Heinrich Heine would call it in

1844, gradually distanced Liszt’s output from his earlier collaborative

pieces. As he assumed the role of the top virtuoso, his musical catalogue

increasingly came to mirror those of his competitors: In the second half

45 The Symphonie fantastique is no exception to Liszt’s usual methods of composing,

revising, and—often—revising and republishing yet again. Mueller succinctly sums up the

difficulty of assessing Liszt’s works based on the often large paper trail that such reworkings create in “Reevaluating the Liszt Chronology: The Case of ‘Anfangs wollt ich fast

verzagen’,” 19th-Century Music 12 (1988): 147.

46 Letter of 2 May 1832, in Liszt, Briefe, 1:6. “Voici quinze jours que mon esprit et

mes doigts travaillent comme deux damnés.”

217

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 218

the journal of musicology

figure 1. Print genealogy of Liszt’s arrangement of the Symphonie fantastique, 1834–77

Nov. 1834:

“Advanced” edition, complete

Schlesinger

Paris (no plate number)

c.1836:

1st edition, complete

Schlesinger

Paris (“M.S.1982”)

“Marche”

Schlesinger

Paris (“M.S.1982”)

early 1838:

218

Complete

Trentsensky and Vieweg

Vienna (“T.etV.2824”)

“Un bal”

Schlesinger

Paris (“M.S.1982”)

“Marche”

Schlesinger

Berlin (“S.2224”)

c.1842:

“Un bal”

Schlesinger

Berlin (“S.2677.A”)

early 1843: “Marche” [arr. Mockwitz]

Schlesinger

Berlin (“S.2817”)

1843/44:

1866:

1877:

Complete

A. O. Witzendorf

Vienna (“A.O.W.2824”)

KEY:

Reprint

“Marche” [rev. Liszt]

J. Rieter-Biedermann

Leipzig & Winterthur (“466”)

New engraving

New edition

2nd edition, complete

Constantin Sander

Leipzig (“F.E.C.L.2893”)

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 219

kregor

of the 1830s, operatic fantasies and shorter pieces based on dance forms

would eclipse his orchestral reductions. His concert programs shrank in

variety, and earlier pieces like his Symphonie fantastique, the exploratory

Apparitions, or the one-movement Harmonies poétiques et religieuses were

heard less frequently, if at all. With such pressure to please his audience,

by what means could Liszt transport his intimate association with Berlioz

of the last half decade onto the concert stage? How could he mediate

the inherently collaborative qualities of the Symphonie fantastique?

Even though Liszt strove to make his arrangements playable, it was

quite rare that one of his Berlioz partitions was mounted in the concert

hall. The ubiquity of Hallé’s reminiscence gives the impression that the

Symphonie fantastique transcription formed a staple of Liszt’s concert

repertoire. And yet, although a complete performance calendar of Liszt’s

concert years is far from complete, current data suggest that Liszt performed the Symphonie fantastique only four times in public.47 (Liszt

never publicly performed the overtures.) And as Table 1 demonstrates,

three out of the four performances were given in Paris, to an audience

that already would have been intimately familiar with Berlioz’s original.

Liszt’s performance of two movements of the work at Vienna on 25 May

1838 for his Abschiedskonzert effectively inaugurated his years as an

independent virtuoso artist, while simultaneously offering a symbolic

farewell to Berlioz and the heady artistic relationship from which they

both had profited for several years.

In the fall of 1834, Liszt was still very much artistically allied with—

indeed, dependent on—Berlioz. The successes and failures of one often

had a corresponding impact on the other. Liszt’s Parisian rise necessitated a trifecta of support in the publishing community, the press, and

the concert hall. Whereas the pianist constantly negotiated—sometimes

fought—with publishers for exposure in print, Berlioz was able to supply both with an accommodating voice in the press and space on the

concert stage, even if on more than one occasion he was forced to conceal his true feelings from the public.48 The older colleague’s review

of the pianist’s rendition of Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” sonata on

47 Owing to their number, Liszt’s concerts have been investigated geographically.

See Geraldine Keeling, “Liszt’s Appearances in Parisian Concerts, 1824–1844,” The Liszt

Society Journal 11 (1986): 22–34, and 12 (1987): 8–22; Malou Haine, “La première

tournée de concerts de Franz Liszt en Belgique en 1841,” Revue belge de Musicologie 56

(2002): 241–78; Michael Saffle, Liszt in Germany, 1840–1845: A Study in Sources, Documents, and the History of Reception (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon, 1994); Luciano Chiappari,

Liszt a Como e Milano (Ospedaletto: Pacini, 1997). Walker (Liszt: The Virtuoso Years) provides a succinct summary of Liszt’s concert activities in tabular form on pp. 292–95.

48 In particular, Liszt had problems convincing Maurice Schlesinger, the publisher

of the Symphonie fantastique, of his abilities as composer. See Anik Devriès, “Un éditeur de

musique ‘à la tête ardente,’ Maurice Schlesinger,” Fontes Artis Musicae 27 (1980): 125–36.

219

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 220

the journal of musicology

TABLE 1

Liszt’s public performances of his arrangement

of the Symphonie fantastique

Date & Location

220

Movement(s)

performed

Notes

28 December 1834

Paris

Salle du Conservatoire

II, IV

Berlioz’s complete Symphonie

fantastique preceded Liszt’s arrangements; Harold Symphony closed the

concert; orchestra conducted by

Narcisse Girard

18 December 1836

Paris

Salle du Conservatoire

II, IV

“Concert donné par MM. Listz [sic]

et Berlioz,” including Liszt’s Grande

fantaisie symphonique and Berlioz’s

Harold Symphony; orchestra conducted by Berlioz

25 May 1838

Vienna

Saale der Gesellschaft

der Musikfreunde

II, IV

“Abschiedskonzert,” with Liszt’s two

“Fragments de la Symphonie fantastique de Berlioz” preceding three

Liszt/Schubert song arrangements

4 May 1844

Paris

Théâtre-Italien

II

Berlioz’s Harold Symphony and overtures to Carnaval romain and Francsjuges performed; Liszt’s arrangement

immediately followed an orchestral

performance of “Le Bal”; orchestra

conducted by Berlioz

12 June 1836 in Paris offers a pristine example of Berlioz’s overlooking

the more excessive elements of Liszt’s showmanship while highlighting

his fidelity to the text.49 As the Thalberg-Liszt debate was heating up in

Paris in January and February 1837, and Liszt attempted in vain to placate the numerous factions within the Parisian beau monde, Berlioz once

again defended his friend with the pen against the pianist’s more vocal

naysayers. The roles would be largely reversed 20 years later in Weimar.

A more enduring component of their success was their rapport on

the concert stage. Particularly in the 1830s, Liszt frequently took part

49 See Katherine Kolb Reeve, “Primal Scenes: Smithson, Pleyel, and Liszt in the Eyes

of Berlioz,” 19th-Century Music 18 (1995): 226–28. Reeve suggests that Berlioz was able to

write a review in good conscience because his nose was buried in the music, thus allowing

him to turn a blind eye to the more unpalatable elements of Liszt’s performing style.

03.JOM.Kregor_pp195-236

4/23/07

9:22 AM

Page 221

kregor

in concerts either organized by Berlioz or containing several compositions by his older colleague. And while the cash-strapped Berlioz often

enlisted Liszt to appear in his concerts, this was hardly unwelcome

exploitation—Liszt made use of the publicity to bolster his own profile

as composer, pianist, and, as soon followed, writer and critic. Moreover,

the mixture of Liszt’s piano works and Berlioz’s orchestral creations