CERP Recommendation on best Practices for Price Regulation

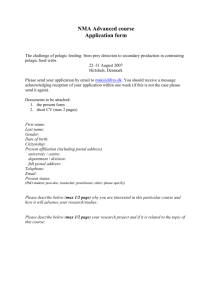

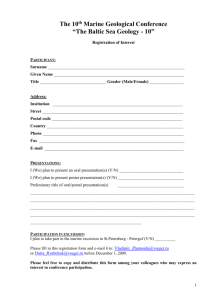

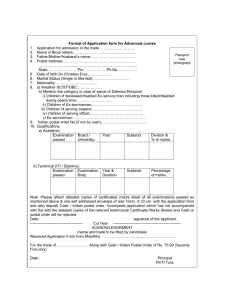

advertisement