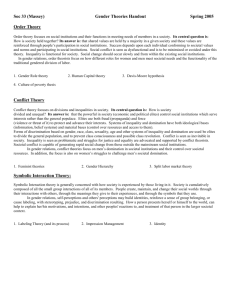

The impact of societal marketing programs on

advertisement