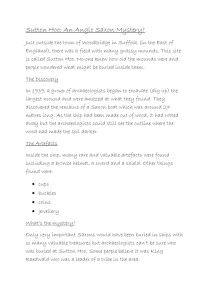

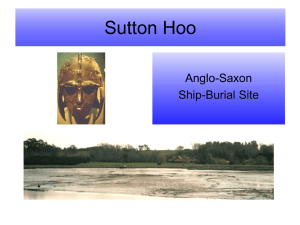

Sutton Hoo & Beowulf: Anglo-Saxon Culture & Archaeology

advertisement

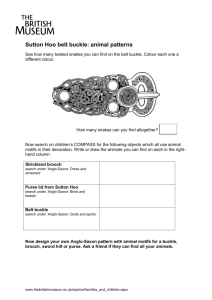

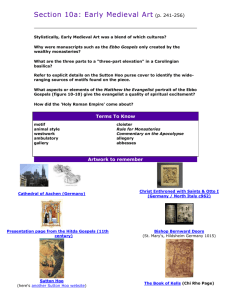

Page 1 Sutton Hoo “They laid then the beloved chieftain, giver of rings, on the ship’s bosom, glorious by the mast. There were brought many treasures, ornaments from far-off lands. Never have I heard that a vessel was more fairly fitted-out with war-weapons and battle-raiment, swords and coats of mail. On his bosom lay a host of treasures, where were to travel far with him into the power of the flood.” -- Beowulf Excerpts from the Anglo-Saxon work Beowulf, which may be found in the class textbook, The Norton Anthology of English Literature, are the first reading assignment for ENGL 2322. Before reading this classic poem, students should investigate a real life archeological discovery -- made in 1938 in the southeastern part of England -- that perfectly illustrates the culture that created Beowulf and serves to emphasize the historical value of the work itself. On an escarpment overlooking Page 2 the estuary of the River Deben in East Anglia, an Anglo-Saxon burial ship was discovered among several burial mounds that dated to Anglo-Saxon times. The timing of the discovery was critical as World War II would break out in Europe just a few months later. The find -- which had to be stored away until the end of the war in 1945 -- is now recognized as the single greatest archeological discovery ever made related to Anglo-Saxon England. It is also considered among the greatest archeological finds of all time for any time period, and its treasures now reside in the British Museum. To briefly explain the name, Sutton is a geographic description for the area of England where the ship was discovered, and “Hoo” is an east English term for a high point of land. In 1938, the land on which these burial mounds resided was owned by Mrs. Edith Pretty, a widow. Stories and strange occurrences had been associated with the mounds on her property for many years, and she finally decided to act in 1937. She contacted the Ipswich Museum, which put her into contact with an amateur archeologist named Basil Brown. This set in motion a series of events that would only begin with the discovery of the ship in 1938. One version of the story of Sutton Hoo is available as a video. Students should view it by clicking on the link provided at right. On the following pages, students may view a sample of the treasures found at Sutton Hoo. The Ship: The remains of the Sutton Hoo burial ship indicates it was almost ninety-feet long and fifteen-feet wide, with room for twenty rowers on a side. The interior seems to have had been covered with a rug or mat on which were placed the possessions of a pagan warrior king: Page 3 The Helmet: Fashioned from a single piece of iron to which are attached deep ear and neck guards, the helmet was fitted with decorative foil panels of tinned-bronze that depict animal motifs as well as scenes from German and Scandinavian mythology. The crest is iron, inlaid with silver wire, with gilded-bronze terminals of stylized animal heads. The eyebrows, too, are of iron and silver wire with boar’s head terminals, beneath which is a row of small squarecut garnets. The nose, beetling mustache, and mouth of the iron face mask also are of gilt bronze. Cooking Pot: Other burial items include many everyday items, such as this cooking pot. Other domestic items included buckets, tubs, and cauldrons. The Sword: The hilt of the sword has a beautiful gold and cloisonné garnet pommel and gold guards. The iron blade is heavily corroded but was pattern-welded, made from eight bundles Page 4 of thin iron rods hammered together to form a pattern of parallel or herringbone lines in the metal. To this core, a cutting edge of carbon steel then was forged. Such patterned swords were highly prized and often passed as heirlooms from generation to generation. Beowulf uses Unferth’s sword, “the curious sword with a wavy pattern, hard of its edge” against Gendel’s mother, but it fails him, just as his own sword Nægling of “ancient inheritance, very keen of edge,” breaks striking the Dragon. The Harp or Lute: Musical instruments like this harp are referenced in the poem Beowulf. It is likely that the poem itself was recited accompanied by music. The Shield: The leather and linden wood shield have rotted away, and there is nothing except its iron boss, gilt fittings, and two magnificent animal figures: a dragon and a bird of prey, both of gilt-bronze decorated with garnets. The Gold Buckle, Shoulder Clasps, and Purse Lid It is the smaller objects, the delicate fittings of the sword belt and scabbard, the zoomorphic gold buckle, and jewel-like shoulder-clasps and purse lid that are most exquisite. There was virtually nothing else like these pieces in Europe at the time, and their artistic virtuosity suggests a master goldsmith working on a royal commission. Page 5 A Great Gold Buckle: The intricate buckle, for example, is hollow and hinged at the back, the belt secured by three pins that project from the underside of the bosses. The other end is placed through the loop and held there by the tongue, which also is hinged. Golden Shoulder-Clasps: The unique pair of cloisonné clasps, which are made of gold, millefiori glass, and garnet, are curved to fit the shoulder, the two matching halves, decorated with intertwined boars, tightly hinged and joined by a gold pin. A Gold-and-Garnet Purse Lid: The purse lid is equally artistic, if not as elaborate, and decorated with animal and abstract designs. Inside were found thirty-seven small gold coins, each deliberately chosen from a different mint in Gaul. Page 6 Symbols of Power: the Whetstone/Stag There also were two unique, but enigmatic, symbols of his power: a whetstone “scepter” surmounted by a small bronze stag on a ring and a mysterious iron stand that may have served as a standard for the king. The Final Mystery Who was either buried or memorialized at Sutton Hoo? As noted in the video, it is doubtful we will ever know, but the best guess at present is Rædwald, king of East Anglia, who died in AD 624/625. This is the same approximate date of the latest Merovingian coins found there. The early historian Bede identifies Rædwald as the fourth bretwalda (“ruler of Britain”) to have overlordship (imperium) of the other kingdoms south of the river Humber. He succeeded Æthelbert, the first English king to be converted, in AD 616 and defeated Æthelfrith, the king of Northumbria, the same year. It was Rædwald, too, who reverted to paganism, says Bede, when he returned from the court of Æthelbert, dedicating altars in his temple both to heathen gods and the Christian one. If so, his defiantly pagan burial preserved, hidden and undisturbed, some of the greatest treasures of Anglo-Saxon art.