The Significance of the Pentangle Symbolism in

advertisement

The Significance of the Pentangle Symbolism in "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight"

Author(s): Gerald Morgan

Source: The Modern Language Review, Vol. 74, No. 4 (Oct., 1979), pp. 769-790

Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3728227 .

Accessed: 10/10/2011 12:01

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Modern Humanities Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to The Modern Language Review.

http://www.jstor.org

OCTOBER I979

VOL. 74

PART4

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PENTANGLE SYMBOLISM

IN 'SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT'

In narratives, where historical veracity has no place, I cannot discover why there should not

be exhibited the most perfect idea of virtue; of virtue not angelical, nor above probability,

for what we cannot credit we shall never imitate, but the highest and purest that humanity

can reach, which, exercised in such trials as the various revolutions of things shall bring upon

it, may, by conquering some calamities, and enduring others, teach us what we may hope,

and what we can perform. (Dr Johnson)

The dominant characteristic of medieval poetry is its objectivity; the primary

interest, that is to say, is moral and not psychological. In his description of the

device of the pentangle on Sir Gawain's shield, the author of Sir Gawain and the

GreenKnight reveals to us that such a moral interest can take exceedingly intricate

forms.l If we are to believe the poet, the pentangle passage is crucial to the understanding of his poem:

And quy De pentangel apendez to bat prynce noble

I am in tent yow to telle, lof tary hyt me schulde

(623)

In carrying out this purpose the poet reminds us of another characteristic of

medieval poetry: the schematic arrangement of its parts. The medieval love of

schematism sometimes results, however, in the production of schemes that are more

ingenious than they are just. It cannot be said that this is a danger that the Gawain

poet has himself wholly avoided. There is not, for example, a consistent relationship

between the five sides of the pentangle and the virtues represented by them; the

fourth group of five, the five joys of Mary (644-50), stands for the single virtue of

courage, whereas the fifth group stands for five distinct virtues (651-55). It seems

likely too that the second group of five fingers (641) has been necessitated by the

poet's scheme and not by his moral exposition.2 These minor blemishes (for such

they are) need not be felt as calling into question the unity of the poem. The judgement of Professor Davis as to the relevance of the fifth group of five is, however, a

good deal more disturbing:

Despite the importance given to this group of virtues by their climactic position, they do not

seem to have been chosen by the poet with especially close regard to the adventure which

follows, or to the particular qualities for which Gawain is later praised. The emphasis at the

end of the poem is almost all on faithfulness to one's pledged word (2348, 238I); this is also

given the leading place as the total significance of the pentangle (626); yet here it is pite that

'passez alle poyntez', though at the same time Gawain practises fraunchyseand fela3schyp

'forbe al 1yng'. It looks as if these qualifying phrases, as well as the associations of the pairs

of virtues, were determined more by form than meaning. (p. 95)

This is a judgement which it is quite impossible to accept if we are to continue to

think of the poem as a masterpiece. Although Dr Brewer seems to regard Sir

Gawain as 'one of the great achievements of English literature', he nevertheless

cautions us against asking too much of it:

1 Sir GawainandtheGreenKnight,11.619-65; referencesare throughoutto the edition of J. R. R.

Tolkien and E. V. Gordon,second edition, revisedby N. Davis (Oxford, I967).

2

of SirGawainand theGreenKnight(London,I965), p. 46.

SeeJ. A. Burrow,A Reading

49

770

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

In particular, Gawain's courtesy is associated with his virtue in the symbolic device of the

pentangle in his shield. The five virtues attributed to him, separate yet inextricably connected like the points of the pentangle, are franchise,fellowship, cleanness, courtesy, pity

(652-5). Really, all these virtues might be said to be subsumed, in one way or another,

under courtesy.... The pentangle shows that the meanings of the words are not distinct.

We are not to attribute the same kind of precision of meaning to part-oral poetry as we are

to the poetry of print. Gawain's five moral virtues are doubtless not analytically set down, and

they all mingle with each other.1

Even Professor Burrow, the best of the modern critics of the poem, is not equal to

the precision of the poet's conception. In his analysis of the semantic range of

trawfe in the late fourteenth century he recognizes the importance of the sense

'fidelity' (OED I) but fails to identify this sense in the pentangle passage itself.2

It would seem that we are to assume that the pentangle symbolism does not exhaust

the moral content of the poem.

In the course of the present article I want to insist upon the justice of the poet's

conception of the pentangle for the meaning of his poem as a whole. In order to do

so it will be necessary to match the subtlety of his moral thinking. It will become

increasingly evident that this is no mean requirement.

The poet explicitly states that the pentangle is a fitting symbol for Gawain (622),

and reinforces his point by the development of an argument which, as Professor

Burrow has shown (pp. 42, 44), takes the form of a syllogism:

The pentangle is a symbol of trawfe (625-26)

I.

2. Gawain isfaythful, that is, trwe (632)

3. Therefore the pentangle befits Gawain (63I)

There is thus a complete identification of the hero and the heraldic device that he

bears on his shield. Just as the pentangle is a unity in which all the parts are interrelated (627-30), so spiritual, moral, and social qualities are united in Gawain

(656-6I). It is important, however, to be clear as to what exactly this identification

implies.

The poet assures us that there is a natural correspondence between the symbol

and its referent (625-26).3 Since this is so, we need to ask ourselves what the natural

resemblance between the geometrical figure and the concept of trawie may be.

As we have seen, the specific point of comparison is a unity made up of interrelated

parts. Professor Burrow is therefore surely right in concluding (p. 44) that trawpe at

line 626 has the inclusive sense of 'integrity' or 'righteousness' (OED 4). This

sense has the support of the pervasive colour symbolism, for the pentangle is 'depaynt

of pure golde hwez' (620).4 In the stanza that follows (640-55) the poet gives an

account of the parts that make up this unity.

1 D. S. Brewer, 'Courtesy and the Gawain-Poet', in Patterns Loveand

of

Courtesy,edited byJ. Lawlor

1966), pp. 54, 68.

(London,

2 See

Burrow, pp. 42-48. Professor Burrow interprets trawpeat line 626 as 'integrity' or 'righteousness' and trwe at line 638 as 'truthful' (pp. 44-45).

3 See Burrow, pp. 187-89.

4 The

symbolic value of gold is explicitly identified by Langland, Piers Plowman, B xix. 83-86:

be secounde kynge sitthe sothliche offred

Ri3twisnesse vnder red golde resouns felawe.

Gold is likned to leute bat last shal euere,

And resoun to riche golde to ri3te & to treuthe.

Reference is to The Visionof William concerningPiers the Plowman,edited by W. W. Skeat (London,

1869).

GERALD MORGAN

77I

The process of semantic widening (from 'fidelity' to 'righteousness') that is to

be discerned in the history of trawbeis by no means an uncharacteristic development

within the moral vocabulary of chivalry. Thus gentilesse can bear the specific sense

of 'generosity' or 'magnanimity', and Chaucer seems to use it in this way in

describing the conditions of an authentic marriage relationship in The Franklin's

Tale. It is by means of a reciprocating generosity (resulting in obedience) that the

issue of sovereignty within marriage is resolved (F 753-63).1 At the same time the

discussion of gentilesse in The Wife of Bath's Tale (not surprisingly, perhaps, in view

of its antecedents) makes it clear to us that Chaucer also uses the word in the broad

sense of 'nobility of character' (D I I 13 ff.). This is the sense that it bears in the moral

ballade on Gentilesse, where it is used synonymously with noblesse (I7). Gentilesse,

that is to say, is the principle of virtue in man:

This firste stok was ful of rightwisnesse,

Trewe of his word, sobre, pitous, and free,

Clene of his gost, and loved besinesse,

Ayeinst the vyce of slouthe, in honestee;

And, but his heir love vertu, as dide he,

He is noght gentil, thogh he riche seme,

Al were he mytre, croune, or diademe.

(8)

Unfortunately these two distinct senses are not formally distinguished either by the

OED or the MED (2 (a) ). Nevertheless the dictionaries do sanction a distinction

of such a kind for the word cortaysye.In The Squire's Tale (appropriately enough)

cortaysyebears the specific sense of 'politeness':

This strange knyght, that cam thus sodeynly,

Al armed, save his heed, ful richely,

Saleweth kyng and queene and lordes alle,

By ordre, as they seten in the halle,

With so heigh reverence and obeisaunce,

As wel in speche as in his contenaunce,

That Gawayn, with his olde curteisye,

Though he were comen ayeyn out of Fairye,

Ne koude hym nat amende with a word.

(F 89)

Its use is also extended, however, so as to include the chivalric ethic in its various

manifestations; at least the MED offers the gloss (s.v. courteisie,n. I): 'the complex

of courtly ideals; chivalry, chivalrous conduct'. Such a meaning is supported by

Dante's definition of courtesy as propriety, that is, behaviour in accordance with the

custom of the court:

E non siano li miseri volgari anche di questo vocabulo ingannati, che credono che cortesia

non sia altro che larghezza; e larghezza e una speziale, e non generale, cortesia! Cortesia e

onestade e tutt'uno: e pero che ne le corti anticamente le vertudi e li belli costumi s'usavano,

si come oggi s'usa lo contrario, si tolse quello vocabulo da le corti, e fu tanto a dire cortesia

quanto uso di corte. (Convivio,II.x.7-8)2

The OED distinguishes between polite behaviour (OED I) and the quality of mind

that leads to it (OED 2). The medieval assumption of a unity between action and

1 Referencesto Chaucerare throughoutto TheWorksof Geoffrey

editedby F. N. Robinson,

Chaucer,

second edition (London, I957).

2

Referenceis throughoutto II Convivio,

edited by G. Busnelliand G. Vandelli, second edition

(Florence, I964).

772

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

intention implies that the external form will be accompanied by the appropriate

inward disposition (a certain magnanimity). Indeed, true courtesy can never be

merely a matter of politeness.

It is a perfect analogy, therefore, that leads to the use of trawfe not only in the

sense of 'fidelity' or 'loyalty' (OED s.v. troth,sb. I), as, for example, in the famous

description of the Knight in the GeneralPrologue:

he loved chivalrie,

Troutheand honour,fredomand curteisie

(A 45)

but also in the sense of 'righteousness' as in the pentangle passage in Sir Gawain.

The OED again does not formally isolate this sense (see truth,sb. 4), and Professor

Burrow is certainly right in questioning its failure to do so.1

Indeed the dictionaries have been unwilling consistently to discriminate between

the broad and narrow senses that we have been considering, but it would seem that

gentilesse,cortaysye,and trawpfehave each in their turn come to be regarded as in

some special sense distinctive or characteristic of the chivalric ethic, while at the

same time retaining their specific meaning. The lack of lucidity in our understanding of such a poem as Sir Gawainwould seem in part to be explained by the refusal

of lexicographers to make such discriminations. At any rate the use of trawbfe

by the

Gawain poet in the comprehensive sense of 'righteousness' suggests the special

significance of fidelity in the moral world that he has created, and gives to the poem

its distinctive orientation. We are reminded of the noble words of Arveragus to his

wife:

Ye shul youretroutheholden,by my fay!

For God so wislyhave mercyupon me,

I haddewel levereystikedfor to be

For verraylove which that I to yow have,

But if ye sholdeyouretrouthekepe and save.

Troutheis the hyestethyngthat man may kepe.

(F I474)

To this extent, therefore, Professor Burrow is right in his insistence upon the

importance of fidelity in the poem.

The Gawainpoet expects his audience to be familiar with the pentangle:

and Englychhit callen

Oueral,as I here,pe endelesknot.

(629)

This ready assumption of familiarity has proved puzzling to the modern reader of

the poem, since scholarship has not been able to provide him with the necessary

references. The symbolism of the pentangle, however, is to be found in some

rather obvious places, the Convivioof Dante and the SummaTheologiaeof St Thomas

Aquinas.2 From a reading of the Convivioit becomes clear that the pentangle is a

common symbol in scholastic philosophy for the rational soul:

1 See Burrow, p.

43. For a fuller discussion of the relationship between fidelity and righteousness

see the Appendix.

2 R. H.

Green, 'Gawain's Shield and the Quest for Perfection', ELH, 29 (1962), 121-39, reprinted

in R. J. Blanch, Sir Gawainand Pearl: CriticalEssays (Bloomington and London, 1966), pp. 176-94,

draws attention to these texts (p. 187), but fails to realize their full significance.

GERALD MORGAN

773

Che, si come dice lo Filosofo nel secondo de l'Anima, le potenze de l'anima stanno sopra se

come la figura de lo quadrangulo sta sopra lo triangulo, e lo pentangulo, cioe la figura che

ha cinque canti, sta sopra lo quadrangulo: e cosi la sensitiva sta sopra la vegetativa, e la

intellettiva sta sopra la sensitiva. Dunque, come levando l'ultimo canto del pentangulo

rimane quadrangulo e non piu pentangulo, cosi levando l'ultima potenza de l'anima, cioe

la ragione, non rimane piu uomo, ma cosa con anima sensitiva solamente, cioe animale

bruto. (Iv.vii. I4)

The symbolism is implicit in Aristotle's De Anima, although the pentangle is not in

fact mentioned:

Typ v t(pEtj

f 5tdapXet

8'EiXt T( itcpi T&VGXrllz TOv Kalit KaCaut& IVeV.i ytap

rIapantiriox;

/ni TE TOV oaXi6aToV Kai ni\ TOv 1nV5X0ov,oiov Iv TCTpayc&0v)

6TOTp6epov

pEv

8 r6 OpERxtK6v

(414 b 28).

Tpiyovov, tv aioCrOlTtKcp

suvalpet

The facts regarding the soul are in the same position as those concerned with figures; for in

any series the first term has always a potential existence, both in the case of figures and of

what possesses soul; for instance, the triangle is implied by the quadrilateral, and the

nutritive faculty by the sensitive.1

Dante's immediate source, however, must be the work of a contemporary scholastic

theologian; St Thomas, for example, conveys the Aristotelian doctrine to us in the

following form:

Et in De Animacomparat diversas animas speciebus figurarum, quarum una continet aliam,

sicut pentagonum continet tetragonum, et excedit. Sic igitur anima intellectiva continet in

sua virtute quidquid habet anima sensitiva brutorum et nutritiva plantarum. Sicut ergo

superficies quae habet figuram pentagonum non per aliam figuram est tetragona et per

aliam pentagona, quia superflueret figura tetragona ex quo in pentagona continetur,

ita nec per aliam animam Socrates est homo et per aliam animal, sed per unam et eandem.

(ST la 76. 3 corp.)2

The Aristotelian (and hence the Scholastic) conception of being is hierarchical;

among living organisms we can observe a hierarchy of vegetative, sensitive, and

rational powers. Each has its corresponding geometrical symbolism: the triangle,

the quadrangle, and the pentangle. The pentangle is therefore established as a

symbol of human excellence or perfection. The general term that the Gawain poet

uses to describe such perfection is (as we have seen) trawfie;the term that Dante uses

is gentilezza or nobilitade.

Nobility, Dante observes, is a term that can be applied without impropriety to

any number of different objects; there are, for example, noble stones, noble plants,

noble horses, and noble falcons as well as noble men (Iv.xvi.5). By the use of this

term we indicate the perfection in each thing of the nature peculiar to it: 'Dico

adunque che, se volemo riguardo avere de la comune consuetudine di parlare, per

questo vocabulo "nobilitade" s'intende perfezione di propria natura in ciascuna

cosa' (IV.XVi.4). When we talk of the nobility of the man we must first of all, therefore, determine what kind of being man is. Here Dante would propose a distinction

between the order of nature and that of reason: 'E a vedere li termini de le nostre

operazioni, e da sapere che solo quelle sono nostre operazioni che subiacciono a

la ragione e a la volontade; che se in noi e l'operazione digestiva, questa non e

umana, ma naturale' (IV.ix.4). That which is distinctive of man is the habit of

1 Aristotle: On the Soul, edited and translated by W. S. Hett (London and Cambridge,

Massachusetts, 1935).

2 Reference is to the edition of T.

Gilby and others (London, I964-).

774

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

choice; the authentic and distinctively human activity is moral activity, the product

of our free will:

Sono anche operazioniche la nostra[ragione]considerane l'atto de la volontade,si come

offenderee giovare, si come star fermo e fuggire a la battaglia,si come stare casto e

lussuriare,e questedel tutto soggiaccionoa la nostravolontade;e pero semodetti da loro

buoni e rei perch'ellesono proprienostredel tutto, perche, quanto la nostravolontade

ottenere puote, tanto le nostre operazioni si stendono. (Iv.ix.7)

Nobility is not, however, to be identified with moral virtue, but is a more comprehensive term; its relationship to virtue is as cause to effect (Iv.xviii.2). Thus nobility

includes not only moral virtues but also natural dispositions, passions, and bodily

graces:

Riluce in essa le intellettuali e le morali virtudi; riluce in essa le buone disposizioni da natura

date, cioe pietade e religione, e le laudabili passioni, cioe vergogna e misericordia e altre

molte; riluce in essa le corporali bontadi, cioe bellezza, fortezza e quasi perpetua

valitudine. (Iv.xix.5)

Once he has defined nobility Dante goes on to consider the means by which we

are able to discover true nobility in individual men. Since all men possess rational

souls (for this is the very definition of the species) no recourse is possible to essential

principles. Instead the means of distinguishing excellence among men is by examining the effects or fruits of nobility, that is, the moral and intellectual virtues:

'Dico adunque che, con cio sia cosa che in quelle cose che sono d'una spezie, si

come sono tutti ii uomini, non si puo per li principii essenziali la loro ottima

perfezione diffinire, conviensi quella e diffinire e conoscere per li loro effetti'

(Iv.xvi.9). Dante specifies the moral virtues in accordance with the analysis that

Aristotle provides in his Ethics(Iv.xvii.4-8). He then proceeds, however, to give the

specific marks of nobility that are to be found in the four ages of man: adolescence

(up to 25), youth (25-45), old age (45-70), and senility (70-80). Youth is for him

the period of man's perfection and maturity (Iv.xxiv. ). There are five marks

of nobility in youth:

soavee vergognosa,

Dice adunque che si come la nobile natura in adolescenza ubidente,

e adornatrice de la sua persona si mostra, cosi ne la gioventute si fa temperata,forte,

amorosa, cortese e

leale: le quali cinque cose paiono, e sono, necessarie a la nostra perfezione, in quanto avemo

rispetto a noi medesimi. (Iv.xxvi.2)

All five qualities are illustrated from the conduct of Aeneas in Virgil's Aeneid,

Iv-vI, that is, from the period of his own youth (Iv.xxvi.8-I4).

It will be apparent that the correspondences between the Convivio and Sir Gawain

are by no means restricted to the mere fact of the pentangle symbolism. That they

are closer than it may even yet appear I hope to show in the detailed analysis of

the pentangle passage in Sir Gawain that now follows.

The Gawain poet conceives of trawp]eas Dante conceives of nobilitade, that is, as a

comprehensive term that includes not only moral virtues but also religious faith

(642-43) and the operation of the senses (640). In his account of the five groups of

five (640-55) he specifies the spiritual, moral, and social virtues that constitute

trawbejust as Dante specifies the fruits of nobility. This may seem to be an obvious

point but it has not always been recognized for what it is.

From the poet's attribution to his hero of perfection in the five senses (640) it

would seem that we are to understand that Gawain does not sin through mere

GERALDMORGAN

775

sensual gratification: that is, the movements of his sensitive appetite are properly

regulated by reason. Thus Gawain is not, for example, guilty offin'amors,the crime

of which is precisely the subjection of reason to desire, as can be seen in

the behaviour of Lancelot in Chretien's Le Chevalierde la charrete,the young lover

in Le Romande la roseof Guillaume de Lorris, and Troilus in Chaucer's Troilusand

Criseyde.lWe may be reminded here of Dante's view that nobility is made manifest

in the whole man, and not merely the rational part of the soul: 'Germoglia dunque

per la vegetativa, per la sensitiva e per la razionale; e dibrancasi per le vertuti di

quelle tutte, dirizzando quelle tutte a le loro perfezioni' (Iv.xxiii.3).

The five wounds of Christ (642-43) are the object of Gawain's afyaunce,that is to

say, the poet's conception of trawfiehas a specifically religious dimension. Those who

are familiar with Chaucer's portrait of the Knight in the GeneralPrologue(A 43-78)

will not find this image of Christian chivalry at all remarkable in a late fourteenthcentury English context. Indeed, this aspect of Gawain's chivalry is reinforced

by the succeeding reference to the five joys of Mary (644-50), for these

are the source of his courage. The attention that is devoted to this fourth group of

five suggests that courage is a significant element in the moral scheme of the poem.

At any rate the Gawainpoet would not be the first to see in his hero this special mark

of distinction; for such a writer as Chretien de Troyes, Gauvain is no less renowned

for his prowess as a knight than for his courtesy. Erec's fame is defined by the fact

that he ranks second only to Gauvain (Erecet Enide, 2230-36); the true prowess of

Yvain is shown in his ability to fight on equal terms with Gauvain (Le Chevalierau

lion, 6 o6 if.; see especially 6447-54) 2

The fifth group of five (651-55) presents a number of related virtues that have a

specifically social extension. Because of the identification of each constituent element in the group and also because of the climactic position of the group as a

whole, it would seem that the poet attaches a special significance to these virtues.

This is to assume, of course, that the poet is still in control of his poem. Since it is

precisely this assumption that ProfessorDavis has called into question, it becomes

especially necessary to consider, with some care, the five virtues that make up the

fifth group.

Fraunchyse(652) is perhaps the least problematic of all of them, for everyone

seems to be agreed that by it the poet intends to single out the virtue of magnanimity

or generosity of spirit. This quality has already been displayed by Gawain in taking

up from Arthur the challenge of the Green Knight, for he does not lay claim to any

special fitness in himself to do so:

Bot for as much as 3e ar myn em I am only to prayse,

No bountebot your blod I in my bod6knowe;

And sylen Pis note is so nys bat no3t hit yow falles,

And I haue fraynedhit at yow fyrst,foldezhit to me.

(356)

Nevertheless it may not be altogether advisable to rule out an implication also of

material generosity (largesse),for it is a moral concept that subsequently becomes of

importance in Gawain's bitter condemnation of himself:

1 On the distinction betweenfin'amorsand amourcourtoissee my article 'Natural and Rational Love

in Medieval Literature', TES, 7 (I977), 43-52.

2 References are to Erec et Enide, edited by M. Roques (Paris, 1970), and to rvain, edited by

T. B. W. Reid (Manchester, 1942).

776

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

For care of by knokkecowardyseme ta3t

To acordeme with couetyse,my kyndeto forsake,

bat is largesand lewt6dat longezto kny3tez.

(2379)

A lofty disregard for wealth remains throughout the Middle Ages a distinctive

quality of those who are of free or noble birth. The fundamental link between

nobility and generosity (already evident in the semantic history of gentilesse)is

reflected by Caxton in his translation (c.I484) of a French version of Ram6n

Lull's LeLibredelOrdedeCauayleria:

'Chyualrye and Fraunchyse accorden to gyder...

the knyght must be free and franke' (I 6/6-9).1 Chaucer himself uses the word

fredomto denote the virtue of generosity in his portrait of the Knight in the General

Prologue (A 46), and also combines the notions of freedom and generosity in

stressing the hospitality of the Franklin (A 339-54). The MED glossesfraunchis(e)

(2(a) ) as: 'nobility of character, magnanimity; liberality, generosity; a noble or

generous act'. Both senses of generosity are relevant here, and are to be found in the

accompanying citations. It seems likely, therefore, that in his use offraunchysethe

Gawainpoet intends us to be aware of both spiritual and material generosity.

The meaning offela3schyp(652) has also not detained readersof the poem for long,

but again it is not so self-evident as it might at first appear. The obvious sense of the

word is 'companionableness', and this is certainly appropriate in its context. Gawain

has indeed already shown to us his companionableness, as ProfessorBurrow notes

(p. 47), in his ability to share with Arthur in such pleasureas is to be derived from the

extraordinary confrontation with the Green Knight:

be kyng and Gawenbare

At bat grenebay la3e and grenne.

(463)

The MED glossesfela3schypin this context (s.v. felaushipe,n. 4) as: 'the spirit that

binds companions or friends together; charitable feeling for one's fellows; charity,

amity, comraderie'. But the moral quality that is distinctive of the relationship

between companions and is the force that binds the companions together is that of

loyalty, and this meaning is at least implicit in the poet's use offela3schyp here.

Such an implication would, of course, be especially evident in a chivalric context.

The best illustration of the moral significance offela3schyp is to be found in The

Knight'sTale in the relationship of Perotheus and Theseus, for the Knight is here

concerned to show by juxtaposition the infidelity of Palamon and Arcite to one

another as a result of a disordered love:

A worthyduc that hightePerotheus,

That felawewas unto duc Theseus

Syn thilkeday that they were childrenlite,

Was come to Attheneshis felaweto visite,

And for to pleye as he was wont to do;

For in this worldhe loved no man so,

And he loved hym als tendrelyagayn.

So wel they lovede,as olde bookessayn,

That whan that oon was deed, soothlyto telle,

His felawewente and soughtehym doun in helle.

(A II9I)

1 Reference is to William Caxton, TheBookof theOrdreof Chyualry,edited by A. T. P. Byles

(London,

1926).

GERALD MORGAN

777

Indeed it is unthinkable that the Gawainpoet should fail to specify the virtue of

fidelity in the pentangle passage.

Whereas some significant meanings in the Gawainpoet's use of fraunchyseand

fela3schyphave in the past been overlooked, the critical discussion on the moral

implications of clannes(653) and cortaysye(653) has been if anything too elaborate.

ProfessorDavis in his note to lines 652-54 (p. 95) observes that clannes'in ME meant

not simply "chastity" but "sinlessness,innocence" generally'.1 But the meaning of

clannesin Middle English is not at issue here; it is the meaning of the Gawainpoet

that we must attend to. As far as that is concerned it is evident that the sense of

'sinlessness'or 'innocence' is quite inappropriate. It is a specific and not a general

meaning that is required by the immediate context, and there can be no doubt

that the meaning which the poet intends is 'chastity'. The use of the word clannesin

this specific manner is, of course, well attested in the late fourteenth century. It is

unambiguously used thus by Chaucer in The SecondNun's Tale:

And if that ye in clene love me gye,

He wol yow loven as me, for youreclennesse.

(G I59)

It is this meaning that gives point to the linking of clanneswith cortaysye:the relationship between the moral concepts the poet is to examine at some length in the

bedroom scenes at Hautdesert. Professor Burrow wishes to stress (p. 48) that

clannesdoes not necessarily imply celibacy. This is indeed true, but it does imply

celibacy or rather virginity outside marriage. ProfessorBurrow goes on to explain

the poet's conception of clannesas follows: 'The poet understood "cleanness", I

am sure, as the generally-accepted condition of knightly love - a condition

which ruled out the "vnleful lust" of adultery as a matter of course, but not truelove or even "love-talking" with one's hostess' (p. 48). Much depends on what we

understand by 'true-love' here, for ProfessorBurrow is perhaps a little too anxious

to assure us (p. 41) that the ideal represented by Gawain is not an ascetic ideal.

There is, of course, no middle ground between adultery (fin'amors)and chastity

(amourcourtois);if by 'true-love' we understand a chaste love before marriage and

by luf-talkyng (927) we understand that such chaste love is accompanied by

courtesy, then ProfessorBurrow's analysis can be accepted. It is worth bearing in

mind here that when Dante attributes to Youth the perfection of loving he is

thinking only of those loves that are lawful; indeed he shows to us that love does not

necessarily presuppose a sexual connotation (Convivio,Iv.xxvi. to-I I). Thus we can

accept the possibility of a chaste love between a young man and another man's

wife. The moral idealism of the pentangle passage certainly rules out any ambiguity

in the poet's conception of clannes.

Cortaysyeis, as we have seen, a word of considerable scope in the fourteenth

century, and it is this aspect of the word that Professor Davis chooses to stress in

was a word of great range and power at this time, embracing

his note: 'Cortaysye

"chivalrous" conduct of all kinds from courtly politeness to compassion and

nobility of mind, and extending to divine grace.' But it is a specific and not a general

meaning that is again required in the present context. This specific meaning is

n. 2 (a)), for the generosity

'politeness' or'refinement of manners' (MED s.v. courteisie

1 Compare MED s.v. clennessen. 2(a), where the glosses 'uprightness' and 'integrity' are also

provided.

778

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

that prompts such politeness has already been specified by fraunchyse.Dante uses

cortesiain this sense in his illustration of the nobility of youth:

Ancorae necessarioa questaetade esserecortese. . . E questacortesiamostrache avesse

Enea questoaltissimopoeta, nel sestosopradetto, quandodice che Enea rege, per onorare

lo corpodi Misenomorto,che erastatotrombatored'Ettoree poi s'eraraccomandatoa lui,

s'accinsee presela scuread aiutaretagliarele legne per lo fuocoche doveaarderelo corpo

morto, come era di loro costume. (Iv.xxvi.I2-I3)

Gawain is in medieval literature the very pattern of courtesy, and it is for this

reason (as we have seen) that he is invoked by Chaucer in The Squire's Tale.

Gauvain's courteous behaviour towards the wounded Erec (contrasted with the

boorishness of Keu) is made much of by Chretien in Erec et Enide (3907-4252).

No better illustration of the Gawainpoet's conception of cortaysyecan be found,

however, than in his own representation of the manner in which Gawain takes up

from Arthur the game proposed by the Green Knight (339-6i).

The Gawainpoet would seem to attach a special significance to pite (654), the

fifth and final virtue of the fifth and final group of five, and indeed he tells us that it

'passez alle poyntez' (654). Unfortunately the form pite is ambiguous in the late

fourteenth century, and can stand for either 'pity' or 'piety'.' The first of these two

meanings is in many ways an attractive one. The sense of 'compassion' fits easily

into the social context of the fifth group of virtues, and points to a quality that

is a familiar element of the ideal of chivalry in the late fourteenth century. The

compassion of Theseus in The Knight'sTale, for example, is evident in his response

to the distress of the company of ladies that greets him on his triumphant return to

Athens:

This gentilduc doun fromhis coursersterte

With hertepitous,whan he herdehem speke.

Hym thoughtethat his hertewolde breke,

Whanhe saughhem so pitousand so maat,

That whilomwerenof so greetestaat;

And in his armeshe hem alle up hente,

And hem confortethin ful good entente.

(A 952)2

Nevertheless there are two serious (and, I think, decisive) objections to the interpretation of pite as 'compassion'. First, it is not at all clear why compassion 'passez

alle poyntez'; second, nothing much is said about Gawain's compassion (unlike

that of Theseus).

An explanation of pite as 'piety' might start with Dante, who does accord to

pietadethe kind of significance accorded to pite by the Gawainpoet, for it 'fa risplendere ogni altra bontade col lume suo. Per che Virgilio, d'Enea parlando, in

sua maggiore loda pietoso lo chiama' (II.x.5). Indeed there is more than a formal

connexion between pity and piety, as the single origin of the two words suggests.

The relationship between the two concepts and the true nature of piety is explained

by Dante as follows:

E non e pietadequellache credela volgargente,cioe dolerside l'altruimale, anzi e questo

ed e passione;ma pietadenon e passione,

uno suospezialeeffetto,che si chiamamisericordia

anzi e una nobile disposizioned'animo,apparecchiatadi ricevereamore, misericordiae

altre caritative passioni. (I.x.6)

1 Both pity and piety are derived ultimately from Latin pietas; see OED's note s.v. pity.

2 See also A

1748-61.

GERALD MORGAN

779

Dante refers to pity as a passion; St Thomas, however, distinguishes between the

passion and the moral virtue:

Dicendumquod misericordiaimportatdoloremde miseriaaliena. Iste autem dolor potest

nominare,uno quidem modo, motum appetitussensitivi.Et secundumhoc misericordia

passio est, et non virtus. Alio vero modo potest nominaremotum appetitusintellectivi,

secundumquod alicui displicetmalum alterius.Hic autem motus potest esse secundum

rationemregulatus;et potest secundumhunc motum ratione regulatumregularimotus

inferiorisappetitus.(ST 2a 2ae 30.3 corp)

Piety, too, can be regarded as a moral virtue, that is, as a specific kind of justice,

consisting in the payment of the debt we owe to our parents and country for our

upbringing (ST 2a 2ae 10.3 corp.and ad. I). Piety is thus nearly allied to religion,

that is, the moral virtue of honouring our debt to God as creator. Since religion

is a more comprehensive term than piety, it contains piety within it; so it is that

piety itself can come to be used for the worship of God: 'Ad primum ergo dicendum

quod in majori includitur minus. Et ideo cultus qui Deo debetur, includit in se,

sicut aliquid particulare, cultum qui debetur parentibus ... Et ideo nomen pietatis

etiam ad divinum cultum refertur' (ST. 2a 2ae IOI.Iad I). There is not only the

virtue of piety, but also the gift of piety, that is, a special habitual disposition of the

soul whereby it is made responsive to the Holy Spirit (ST 2a 2ae

I21.I

corp.). The

gift of piety is the honouring of God not as creator but as father. It is more excellent

than the virtue either of religion or of piety, for the gifts of the Holy Spirit are in

themselves more excellent than the moral virtues (ST 2a 2ae I21.I ad 2).

Dante would seem in the Convivioto have had in mind primarily the gift of piety

(compare ST 2a 2ae 121.2 ad 3); the author of Sir Gawainuses pite rather in the

sense of the virtue of religion, that is, the prevailing modern sense of piety (OED

II. 2). ProfessorDavis rejects this interpretation (p. 96) because 'Gawain's piety has

been fully shown in 642-50, and further emphasis on it would be otiose'. This

observation does less than justice to the accuracy of the poet's thought. The five

joys of Mary are introduced by the poet to account for Gawain's courage and not

his piety (644-50). The five wounds of Christ are the object of Gawain's faith or

belief (642-43); faith is a theological virtue (see ST ia 2ae 62.3 corp.)and not a

moral virtue. Piety is not faith but the scrupulous observance of religious duties.

Since it is clear that such piety is an important element in the poet's subsequent

representation of Gawain, it should be clear also that in the pentangle passage pite

means 'piety' and not 'pity'.

If the foregoing analysis of the system of spiritual, moral, and social values

symbolized by the pentangle is substantially correct. then it is evident that the

correspondencebetween Dante's conception of the nobility of youth and the Gawain

poet's conception of the nobility of his hero is striking indeed. Four of Dante's five

marks of such nobility (courage, love, courtesy, and loyalty) are conspicuously

present in the pentangle passage; the remaining mark, that oftemperance, we may

perhaps suppose to be accounted for in the proper regulation of desires that is

implicit in the first group of five (640). It is not, of course, suggested that the

Gawainpoet is in any direct manner indebted to Dante; the truth would seem to be

rather that the Convivioand Sir Gawainboth belong to moral and intellectual worlds

that have been formed by the habits and presuppositions of Scholastic philosophy.

If we look more closely at the common literary inheritance we shall undoubtedly

discover further points of contact. Two features of Dante's discussion of nobility in

780

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

particular seem to me to be of special interest for our understanding of Sir Gawain:

the first is that the life of Aeneas is taken as establishing the true pattern of nobility;

the second is that youth is the period in which such nobility is raised to its highest

level of excellence.

It is the purpose of the first stanza of Sir Gawainto show to us that the nobility of

Camelot is to be explained in part by its origins. The poet moves in a logical progression, from 'Ennias be athel, and his highe kynde' (5), to Felix Brutus the 'burn

rych' (20) who founded Britain, and to 'Arthur be hendest' (26) of the kings of

Britain. His strategy here would seem to be quite unambiguous. Nevertheless it has

to some extent been disputed. A number of readers (among them ProfessorDavis)

would urge us to identify Aeneas with 'pe tulk pat be trammes of tresoun per

wro3t' (3). The language of the poet, it has to be confessed, does admit of this

possibility, for 'Hit watz. .' (5) may either refer backwards to 'pe tulk' (3) or

forwards to 'Ennias Pe athel' (5). Moreover there is a medieval tradition, descending from Guido de Columnis and well known to English writers,as ProfessorDavis

notes, which associates Aeneas with the act of betrayal of Troy. Professor Davis

assures us that athelrefers only to nobility of birth and that 'the legend of Aeneas'

treachery did not embarrass writers in English who wished to trace the descent of

the Britons from him, through Brutus' (p. 70). These assurances,however, leave all

the important questions unanswered. What possible reason can the Gawainpoet

have for drawing our attention to the treachery of Aeneas at the beginning of his

poem? It is surely possible for a great poet (such as the Gawainpoet) to be disturbed

by the treachery of Aeneas even if a host of lesser writers are not. When the subject

of his poem is trawfe itself, the issue has to be properly faced; either there is a

significance in the treachery of Aeneas or Aeneas is not a traitor at all.

The fact is that it is not sufficient for the interpretation of a poem to state the

existence of a tradition when more than one tradition is available to a poet. It is

necessary to know the particular tradition within which a single poem has been

written, since a poem is a unique artefact for which generalities will not in the end

suffice.' If a poem cannot be explained by the presuppositions of one tradition, we

must not allow the poem itself to be deformed for the sake of the tradition; we are

compelled rather to deny the relevance of the tradition to the poem.

No one who is familiar with Virgil (a Dante, for example) would accept the

notion of a treacherous Aeneas. The issue of infidelity is at the moral centre of

TroilusandCriseyde,but it is Antenor and not Aeneas who is associated by Chaucer

with the betrayal of Troy. Indeed the irony of Criseyde's exchange for Antenor

depends upon the reputation of Antenor for treachery:

This folk desirennow deliveraunce

Of Antenor,that broughthem to meschaunce.

For he was aftertraitourto the town

Of Troye; alias, they quyttehym out to rathe!

(iv.202)

It is the tradition of Antenor's treachery that makes sense of the opening stanza of

Sir Gawain,and the one we must therefore assume the poet himself to have had in

mind.

1 A clear understanding of this critical principle is vital if we are to appreciate the poet's conception

of Gawain himself; Chretien's Gauvain, for example, moves in a different moral world from that of

Malory's Gawain.

GERALD MORGAN

78I

The assumption that the nobility of Aeneas is merely a matter of birth is, moreover, highly questionable in a late fourteenth-century literary context. The fourth

tractate of the Conviviohas been in part written to refute so absurd (inconveniente)

an error as that which would relate nobility to birth (see iv.xiv.6 ff.), for 'E gentilezza dovunqu'e vertute' (Canzone,iii.ioI). This doctrine is congenial to at least

one great English poet of the late fourteenth century:

Vyce may wel be heir to old richesse;

But ther may no man, as men may wel see,

Bequethe his heir his vertuous noblesse.

(Gentilesse,15)

It seems, therefore, that for the Gawainpoet Aeneas has a moral significance comparable to that which he possesses for Dante; that is why indeed his nobility is

invoked at the beginning of the poem.

In the third stanza the poet introduces us directly to the nobility of Camelot:

De most kyd kny3tez vnder Krystes seluen,

And be louelokkest ladies pat euer lif haden,

And he ke comlokest kyng bat be court haldes.

(5I)

Here indeed we see behaviour that is proper to a court: jousting, singing, and

dancing (41-49). We may well be reminded of Chaucer's description of the Squire

in the GeneralPrologue:

He koude songes make and wel endite,

Juste and eek daunce, . . .

(A 95)

The company at Camelot is in joyous mood, for it is celebrating the birth of Christ,

but the merriment is never unseemly; the revelry is splendid but also fitting (40).

HIere too we shall find valour as well as courtesy; the poet indeed tells us that:

Hit were now gret nye to neuen

So hardy a here on hille.

(58)

This combination of fame, courtesy, and courage is made up of classic chivalric

values. All three are brought together by Chretien in his initial presentation of

Erec (Erec et Enide, 81-93) and illustrated by him in the adventure of the sparrowhawk. Chaucer includes them in his portrait of the Knight (A 45-46). It is the wide

recognition accorded to these ideals that leads the Gawain poet to observe that 'al

watz tis fayre folk in her first age' (54). Here again, however, is a linguistic ambiguity, the resolution of which is crucial to our understanding of the poem. The

ambiguity can perhaps best be illustrated by the definitions supplied by the OED

for prime, sb.1:

The 'springtime' of human life; the time of early manhood or womanhood, from

II.8.

about 21 to 28 years of age.

Of human life: The period or state of greatest perfection or vigour, before strength

III.9.

begins to decay.

Professor Davis thinks that it is the first of these two senses that the Gawain poet

has in mind (p. 74). But the description that precedes the phrase 'first age' is one

in which the perfection of Camelot is fully displayed. It is surely not possible to

improve upon the courtesy that is exhibited in this description. The third stanza of

782

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

the poem indeed bears witness to the fame of the Round Table and the poet's

essential sympathies. It is the fame of Camelot which brings the Green Knight

there to put it to the test (256-64). To suppose (as some critics have done) that the

society of Camelot is in some special sense flawed is to render the moral design of

the poem as a whole incomprehensible. The poet describes to us the court in the

full vigour of its youth, that is, the period of its greatest perfection. Dante for one

would have had no difficulty in recognizing the justice of this portrait.

The pentangle passage in Sir Gawaindefines for us the moral limits within which our

imaginations are to operate. Two important conclusions at least emerge from a

reading of it. The first is that human behaviour is a matter of considerable complexity, and that man is called upon to reconcile the divergent claims that are made

upon him at the moral level. The second is that Gawain (embodying to the full

the values of Camelot) is a perfect representative of Christian chivalry.

This second conclusion can be the source of some confusion in our reading of

the poem. There is a danger of treating the pentangle symbolism with the wrong

kind of rigour, and thus of supposing that Gawain's behaviour is subjected to a

more critical scrutiny than the poet intends. It is necessary to clarify the nature of

the claim that the poet makes on behalf of his hero. Dante has shown us the truth

when he says that nobility is the perfection of each thing in accordance with the

peculiarity of its nature. Here we need to recognize that the pentangle is not by

definition a perfect unity; it possessesgreater unity than a quadrangle but less than

a circle. We do not therefore expect of Gawain perfection that is appropriate to

angelic being or to God himself.1Gawain's perfection does not require us to suppose

that he is without sin and that moral behaviour is for him inevitable. Indeed the

first supposition would be heretical and the second would offend against the very

definition of moral behaviour (that is, of activity dependent upon a free and

deliberate act of will). But that Gawain's behaviour is perfect of its kind we need

not doubt; the symbolism of the girdle does not call into question Gawain's perfection, but defines more precisely for us the limited perfection that is possible for

human beings. We can say this because the poet has defined with great care the

nature of Gawain's failing: the inordinate fear for life that leads him to accept the

girdle from the lady (I846-67). Against Gawain's failing, however, are to be set

the fruits of his nobility, and to these it is appropriate that we should now turn.

The moral subtlety of Sir Gawainis reflected in the intricacy of its design. The

disposition of hunting scenes and bedroom scenes indeed forms part of a structural

analogue to the pentangle symbolism; in this way we are constantly made aware

of the relationship between the two in the agreement of Gawain and Bertilak to

exchange winnings, and hence of the larger moral significance of the events that

take place in the bedroom. On a yet broader front the poet has dovetailed the

beheading game and the exchange of winnings, the one (as we later discover) being

made dependent on the outcome of the other. At the end of her trial of Gawain's

chastity and courtesy the lady shifts her ground and, going beyond the immediate

moral environment, successfully appeals to Gawain's fear for his own life. It is by

1 The

figure of the circle is used by Boethius in the De consolatione

philosophiaeto represent the divine

simplicity; see Book II, Prosa I2, I6o-62, 179-84, and I94-97 (in Chaucer's translation).

GERALD MORGAN

783

means of this complex interlocking structure that the poet does justice to the ideas

that he has first directly broached in the pentangle passage. How coherently he has

developed them I hope now to show by taking up the moral issues in the order

that he has presented them to us there.

From the pentangle passage (644-50) it appeared that courage was an important

element in the poet's moral design, and indeed Gawain's failure is ultimately a

failure of courage. But it would be gross to suggest that Gawain lacks courage.

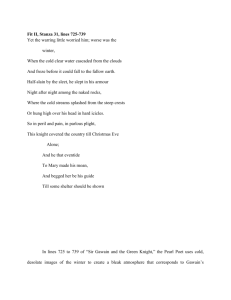

His courage is displayed at the beginning of his quest for the Green Chapel in countless fights against strange knights and wild animals (715-25). In the third fitt the

poet isolates fear for life as the source of Gawain's failing, but in the first part of the

fourth fitt he goes on to consider the extent to which Gawain may be considered

guilty of cowardice. In the second arming scene he focuses upon the girdle (2030 if.),

placed cunningly in juxtaposition with the pentangle (2026-27), and stresses once

again the true motive behind its acceptance (2037-42). It is a testimony to the

sensitivity of his moral analysis and the authenticity of his portrayal of Gawain's

excellence that we should not feel it inconsistent of him at this point to refer to

Gawain as 'pe bolde mon' (2043).

Indeed it is precisely to establish how far (and how little) Gawain has compromised his reputation for valour that the poet has constructed for him a further

The aim of the guide is to exploit Gawain's

test, that of the guide (2091-2159).

in

to

him

unfaithful to his pledged word to the Green

order

make

fears

legitimate

as

one

who is concerned only for Gawain's wellThe

himself

guide presents

Knight.

being; the circumspect politeness of his address leaves us no cause to doubt

his motives (2091-96). The guide assures Gawain of the formidable size and merciless nature of his adversary; the keeping of his pledge involves the certainty of

death (2097-2 7). These are all truths that we ourselves can vouch for, and there

is no need for Gawain to misbelieve the truth of the guide's words. What a loss of

courage would mean here emerges all too clearly from the guide's promise to conceal a failure to keep the appointment (2I 8-25). His invocation of God, Christ,

and the Saints (2119-23) and his assurance of fidelity ('I schal lelly yow layne'

(2124)

play deliberately upon the moral ambiguities of the situation, for the

Virgin Mary is the source of Gawain's courage and a faithful concealment would

involve an act of infidelity. On this occasion Gawain clearly discerns the nature of

the temptation and courteously turns down the guide's offer (2127-28);

we can

appreciate the effort that the exercise of courtesy here costs Gawain ('and gruchyng

he sayde' (2126)) for the guide's suggestion is an affront to a fundamental ideal of

knighthood (2129-31). The guide's response to Gawain's clear statement of the

moral issues and the firmness of his resolve discloses at once to us his true role as

tempter, for he abandons the polite yow (2091, etc.) for the contemptuousfou

(2I40, etc.). His use of the oath 'Mary!' (2 40) has an ironic appropriateness, for

Gawain has revealed his commitment to that lady by showing his courage. It is

important to note, too, that Gawain's faith (afyaunce)is still firmly placed in God

(2136-39 and 2156-59). One consequence of the interrelationship of the virtues is

that the acceptance of the girdle has involved Gawain in the yielding to practices

that are in themselves superstitious.

Between the departure of the guide and the receipt of the blow, or rather blows

as it transpires (2160-2238),

the poet takes the opportunity to exploit to the full the

elements of suspense that lie within his story. He describes the desolation and

784

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

seeming hostility of the place in which Gawain finds himself (2 63 if.): the rough

rocks that graze the skies (2166-67); the water boiling in the stream (2172-74);

the grass-coveredmound itself (2 180-84). The devilish associations that are aroused

in the mind of the knight (2 85-96) correspond perfectly to our sense of the menace

that has been created within the atmosphere of the poem at this point. This suggestion of menace is immediately confirmed by the description of the hideous noise

of grinding (2199-2204 and 2219-20) and of the size and sharpness of the Green

Knight's axe (2222-26). It is worth noticing how the poet focuses on the fearsome

qualities of this 'felle weppen' (2222), a massive blade, four feet long, newly

sharpened on a whetstone (2223-26). There is no occasion here for the poet to

dwell on the fine craftsmanship of which it is a product (compare 214-20). There

is no comfort either for Gawain in the mood of the man who wields it; he strides

forward 'bremly brope' (2233). The poet has thus superbly concentrated his effects

and, what is more, has presented them to us from Gawain's point of view (2163,

2 I85 ff., and 2205 ff.). We are made sharply aware of the dangers that he confronts

and the fears that they inspire, and as a result we are bound not only to recognize, as

the Green Knight does (2237-38), his great fidelity, but also the courage that such

fidelity requires of him.

In the account of the blows that Gawain receives at the hand of the Green

Knight (2239-2330)

the poet reveals to us a precision in his moral analysis that we

have often been called on to acknowledge before. Gawain's physical response

indicates at one and the same time the extent and limitations of his courage. We are

led to admire the courage with which he presents himself for his death and controls

his fears (2255-58) and feel the justice of the poet's description of him as one that

'do3ty watz euer' (2264). But it is at this point that the great courage of the knight

fails him, for he flinches as the blow descends (2265-67). This failure of nerve

provokes the Green Knight to the sternest of recriminations for such an act of

cowardice (2268-79). This is the second of the judgements that the Green Knight

passes on Gawain (see 2237-38), and we may feel that it is somewhat overdone. At

any rate it is difficult to deny the force of Gawain's observation that he cannot

restore his own head in the manner of a Green Knight (2280-83). Before the

second blow is offered Gawain gives his word to receive it without flinching (228487); this pledge enables the poet to place before us once again the admirable

combination of fidelity and courage in his hero (2292-94), sustained in the

face of the severest of pressures (2288-89). The good knight offers no resistance on

the third occasion until the blow has been struck, and again in the face of the

severest provocation (2305-308).

The manner in which Gawain receives the three blows aimed at him enables us

to see his fidelity and especially his courage in their proper perspective. Gawain's

yielding to his fears in the acceptance of the girdle is mirrored by his flinching from

the first blow; on both occasions ourjudgement of him is moderated by our constant

awareness of the great courage that he displays. There is no need for us to minimize

the seriousness of Gawain's failing (the sinfulness of the human condition is not

something that the poet wishes lightly to accommodate), and ProfessorBurrow is

again right to remind us of its gravity (pp. 133-40). But at the same time we can

appreciate the excellence of Gawain; the poet intends us with the Green Knight

to admire the courage of the man (2331-35), and to see that in this life authentic

courage in its noblest manifestations coexists with the weakness of our fallen nature.

GERALD MORGAN

785

It will be evident from this discussion of Gawain's courage that the emphasis

placed upon it in the pentangle passage is in no sense misleading. We may accordingly turn to the fifth group of virtues in the confidence that each of its constitutive

elements will be duly represented in the course of Gawain's quest for the Green

Chapel.

It is not always easy to isolate Gawain's generosity, since it is so closely related to

his courtesy. Nevertheless it is very much in evidence in the bedroom scenes.

Gawain is, for example, very ready to attribute the advances of the lady to her own

generosity of spirit (I263-67). In the same way he is able characteristically to turn

aside the argument (I495-97) that he should use force to gain his ends:

'3e, be God,' quop Gawayn,'goodis your speche,

Bot Preteis vnpryuandein pede per I lende,

And vche gift pat is geuen not with goud wylle.'

(1498)

The many scenes of celebration at Bertilak's court establish the value offela3schyp

in the sense of companionability (I I 13 f., 1398 if., and I664 ff.). The companionship of Gawain and Bertilak gives rise to theforwardewhich calls for fidelity on both

sides (I I05-I2). This is a solemn and binding agreement; hence the importance of

the statement of the terms, their fulfilment (I383-97 and I635-47) and renewal

(I404-o8 and 1676-85). At the same time Gawain's fidelity to his covenant with

the Green Knight is tested. The lengthy description of hisjourney through England

(691 if.) expresses his fidelity to his pledged word to the Green Knight that he will

seek him out for the return blow (392-403). Moreover he does not neglect his

promise to the Green Knight in agreeing to the game proposed by Bertilak (i6707 ). The issue of fidelity is also at stake in the acceptance of the girdle. The lady

entreats the knight faithfully to conceal the girdle from her lord (I862-63); in

consenting to this entreaty (1863-65) Gawain compromiseshimself, for he cannot at

the same time fulfil his agreement with the lord to exchange winnings. He is guilty

of an act of infidelity to his pledged word and also by the same token an act of

covetousness in withholding that which should properly belong to another. While

we are thus aware of the moral repercussionsof this single act of consent we remain

at the same time aware of Gawain's great moral worth. This combination of moral

excellence and sinfulness is perfectly illustrated by the poet when he describes how

Gawain does in fact conceal the girdle (I874-75). The use of the adverb holdely

(i875) is especially fitting, for it brings to our attention Gawain's fidelity to his

word at the very moment of infidelity. The poet subsequently represents Gawain's

infidelity in objective terms by dressinghim in a 'bleaunt of blwe' (1928), for blue is

the colour of fidelity: that is why Criseyde bids Pandarus take a ring with a blue

stone to Troilus to assure him of her continuing faithfulness (TC, iii.885).

The virtues of chastity and courtesy can perhaps be treated together, since it is

a fundamental premise of the Gawainpoet that cortaysyeis consistent with clannes

(653). This contention is unremarkable in the courtly literature of England in the

late fourteenth century, and it is one to which the poet insistently returns. Gawain's

greeting of the two ladies at Bertilak's court, the old and the young one alike, is

impeccably courteous (970-76). The conversation between the lady and Gawain

on Christmas Day is a perfect example of what the poet has in mind in the

pentangle passage:

50

786

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

Bot 3et I wot lat Wawen and Pe wale burde

Such comfort of her compaynye ca3ten togeder

bur3 her dere dalyaunce of her derne wordez,

Wyth clene cortays carp closed fro fylbe.

(IO10)

We see, too, how disturbed Gawain is within himself when the lady, on the evening

of the second day of her temptation of him, goes beyond the bounds of propriety

(1658-63). On the third day she comes close to breaching the knight's defences:

For pat prynces of pris depresed hym so Pikke,

Nurned hym so ne3e Pe Pred, pat nede hym bihoued

Ober lach ler hir luf, ober lodly refuse.

He cared for his cortaysye, lest crabayn he were,

And more for his meschef 3if he schulde make synne,

And be traytor to pat tolke pat pat telde a3t.

(1770)

Professor Burrow insists (p. Ioo) that the poet was not 'so preoccupied with chastity

that he could use the word "sin", without further ado, to mean "sexual sin" or sin

in the Sunday papers' sense' (as though the virtue of chastity can be discredited by

sensational modern journalism). It is unusual for Professor Burrow himself to take

so one-sided a view of the poem. He is right to stress the importance of fidelity

here, but wrong to diminish by comparison that of chastity. These lines indeed

provide yet another excellent illustration of the pentangle symbolism, for they show

how an act of unchastity immediately involves an act of infidelity.

Finally we come to the virtue of piety. The Gawain poet would have been

dismayed to find that it was possible for the piety of his hero to have been

called into doubt. The evidence in the text for Gawain's piety is indeed quite

unambiguous. His piety is shown in his anxious care for his devotions on Christmas

Eve (748-62). The festival of Christmas is scrupulously observed at Bertilak's court

On the

(930-40), both with a fitting gravity (soberly,940) and joyously (995-1000).

mornings of the first two temptations by the lady, Gawain gets up and goes to

and I558). On the third morning he goes to confession:

Mass (I309-II

Pere he schrof hym schyrly and schewed his mysdedez,

Of be more and le mynne, and merci besechez,

And of absolucioun he on Pe segge calles;

And he asoyled hym surely and sette hym so clene

As domezday schulde haf ben di3t on Pe morn.

(1880)

Some very fundamental and orthodox theology is involved here, for a formal

acknowledgement of one's sins and absolution of them are certainly necessary in

the Middle Ages for those in expectation of death (subsequently justification

becomes possible by faith alone). The supposition that Gawain's confession is

invalid ('pretty hollow by any standards - and not least by those of the medieval

church', as Professor Burrow tells us (p. o06)), makes no sense of the poem's moral

design, and indeed is difficult to reconcile with any conception of nobility whatsoever. The ultimate cause of the error is the habit of viewing behaviour in

psychological rather than in moral terms. The theological objections that Professor

Burrow raises against Gawain's confession can be answered but need not be

GERALD

MORGAN

787

answered here, for they are simply irrelevant to the poem itself. The point is

that Gawain's confession is the most lucid illustration of his piety that the poet has

given us; here indeed is the 'pite Pat passez alle poyntez'.

The fourth fitt embodies a number of different judgements of Gawain's behaviour:

those of the Green Knight, of Gawain himself, and of Camelot. It would be true

to say, I think, that these judgements are not so much conflicting as presented from

different points of view. We have already seen, indeed, that the Green Knight

himself makes two formal judgements of Gawain during the repayment of blows;

he accuses Gawain of a wretched and uncharacteristic cowardice after the first

(2268 if.), and looks with an unfeigned admiration on his valour after the third

(2331 if.). We should not wish to argue, however, that there is a moral contradiction here, for both responses are attuned to their respective situations. We shall be

unlikely wholly to discount either, although it is important that we should see the

one in its proper relation to the other.

I should like to argue, on the other hand, that the final judgement of the Green

Knight (2336-68) is especially authoritative, and is one that the poem as a whole

sustains. There are a number of factors which make this conclusion persuasive. The

first is, of course, the judgement itself. Here we can see that the Green Knight does

not withhold judgement but moderates it, and does so in accordance with our

experience of the moral issues in the poem as they have been presented to us. Thus

he recognizes Gawain's supreme moral excellence (2363-65), but recognizes also

that his behaviour is not wholly free from blame (2366). This sense of Gawain's

excellence fits perfectly the expectations that the pentangle passage has aroused,

although we must insist once again that the pentangle passage does not encourage

false assumptions of an absolute perfection at the human level (note the use of the

comparative form of expression at 654-55). It is true that when Gawain leaves

Bertilak's castle for the Green Chapel he wears the girdle next to the pentangle

(2025-36), but we can hardly suppose as a result that the pentangle has been shown

to be unfitting as a symbol. What the juxtaposition of the pentangle and girdle

involves (and what we perhaps see more clearly than we did before) is that the

sense of man's spiritual and moral excellence includes for the poet also the recognition of his sinfulness. The pentangle continues to symbolize Gawain's excellence,

and the justice of this symbolism is fully borne out by the Green Knight's words:

'On be fautlest freke pat euer on fote 3ede' (2363). The congruity of the Green

Knight's judgement with the poet's moral analysis is thus evident throughout;

nowhere is this more noticeable than in the recognition of Gawain's motive in

accepting the girdle (compare, for example, 2037-42 and 2367-78); fear for life

has led to an act of infidelity (2366).

It is the knowledge that the Green Knight displays in this recognition-scene (as

Professor Burrow fittingly describes it) that makes a marked contribution to our

sense of his authoritativeness, for it is not only Gawain who is enlightened but also

the auditors of the poem. For the first time we are made aware of the fact that the

outcome at the Green Chapel turns upon Gawain's success or failure in the exchange

The interweaving of the two agreements not only

of winnings agreement (2345-6I).

matches the poet's understanding of the complexity of moral behaviour but also

enables him to express his judgement of the hero in objective terms. Thus the first

two feints repay Gawain's exemplary fidelity on the first two days of temptation by

788

'Sir Gawainand the GreenKnight'

the lady (2345-55) and the slight knock (tappe,2357) his partial failure on the third.

Since it is the Green Knight himself through whom this objective judgement is

conveyed, it is impossible for us not to accord to his words a special respect.

The knowledge which the Green Knight possesses contrasts very markedly

with Gawain's ignorance, and here we refer not only to the fact of the Green

Knight's contrivances (2360-62), his identity and motives (2444-62), but also to

Gawain's lack of moral awareness until the issues have been fully disclosed to him.

Gawain and the Green Knight are thus fittingly represented as standing in the

relationship of penitent and confessor (2385-94). In the Green Knight's judgement

we have seen how an act of cowardice (an inordinate love of life) leads to an act of

infidelity (2366-68), but also how that view is tempered by the acknowledgement of

Gawain's excellence. Gawain takes a much less sympathetic view of his own case,

but his moral analysis is not formally to be faulted. He stressesmore fully than the

Green Knight chooses to do the moral repercussionsof his act of cowardice: it leads

not only to infidelity (2381-83) but also to covetousness (2374 and 2380-81);

that is, to the wrongful withholding of the girdle. This awareness of the interrelationship of the virtues is, as we have seen, a central concern of the poet. The

difference between the Green Knight's judgement and that of Gawain lies not so

much, however, in the stress that each gives to the interrelatedness of virtues, but

to the difference in their points of view. The Green Knight as judge looks with

benign (but not negligent) tolerance on Gawain's exertions (2331-35), but

Gawain himself is filled with shame (2369-72). Although we may recognize the

objective validity of the Green Knight's response we may also feel that Gawain's

shame is appropriate to the sense of his own sinfulness.1 Thus while the Green

Knight sees the love of life as an extenuating element in Gawain's infidelity (2368),

Gawain himself sees cowardice as the source of covetousnessand infidelity (2379 ff.).

The revulsion that Gawain feels is everywhere apparent in his response to the

Green Knight (2374 f.), but we should not mistake the difference of tone as

evidence of a shift in the moral situation. The Green Knight's words should not be

taken to imply a dismissive attitude towards Gawain's fault.

The judgement of the court in its turn must be placed in contextual perspective,

and is intended neither to supersede nor to belittle either of the earlierjudgements.

It is proper that the court should rejoice in the safe return of its noblest knight

(2489-93), and we may recall here the initial identification of Gawain with that

court (109 if.). By accepting the girdle as a badge (2513-22) the court once again

insists upon the identification, and this is surely not a cause for shame. Gawain's

fault serves not so much to qualify knightly renown as to define it; hence the

girdle can be taken as a fitting symbol of 'Pe renoun of Pe Rounde Table' (2519).

1 The assumption that true contrition should be

accompanied by the bitterness of shame is strikingly

illustrated by Langland, Piers Plowman,B xx. 278-82:

For persones and parishprestes bat shulde be peple shryue,

Ben curatoures called to knowe and to hele,

Alle lat ben her parisshiens penaunce to enioigne,

And shulden be ashamed in her shrifte; ac shame maketh hem wende,

And fleen to be freres ...

See also B xx. 302-2I and 352-77.

GERALD MORGAN

789

APPENDIX: JUSTICE, RIGHTEOUSNESS, AND TRUTH1

a full understanding of Christian thought concerning justice

I. Justice and Righteousness:

requires a recognition of the following propositions and concepts:

(i) Christian moral doctrine is characterized by the integration of love and justice.

Love is, however, more fundamental than justice.

(ii) Divine justice is a primary cause of action, human justice a secondary or dependent cause. The interrelationshipof the supernatural and natural ordersis indeed

a persistent theme of St Thomas. Thus, in discussing whether the goodness of an

act of will depends upon the Eternal Law he observes:

Dicendumquod in omnibuscausisordinatiseffectusplus dependeta causaprima

quam a causasecunda,quia causasecundanon agit nisi in virtuteprimaecausae.

Quod autem ratio humana sit regula voluntatishumanae, ex qua ejus bonitas

mensuretur,habet ex lege aeterna,quae est ratio divina. (ST Ia 2ae I9.4 corp.)

(iii) Human virtues are defined by St Thomas as good operative habits, that is, they

are ordered to act and not to being (ST Ia 2ae 55.1-3). It is common, therefore,

for virtues to be defined by the activities that correspond to them; this is the case

in the standard definition of justice as 'perpetua et constans voluntas jus suum

unicuique tribuendi' (see ST 2a 2ae 58. ). A strict terminology requires the

maintenance of the distinction between habit and resultant activity. It is indeed

the distinction between justice and righteousness:

Ad secundumdicendumquod neque etiamjustitia est essentialiterrectitudo,sed

causalitertantum:est enim habitussecundumquem aliquisrecte operaturet vult.

(ST 2a 2ae 58.1 ad 2)

(iv) Although justice properly refers to a right order in man's actions it is also used

analogically in reference to inner rectitude; that is, the condition of being just:

Alio modo diciturjustitia, prout importatrectitudinemquamdamordinisin ipsa

interioridispositionehominis,prout scilicet supremumhominissubditurDeo, et

inferioresvires animae subduntur supremae, scilicet rationi; et hanc etiam

dictam.(ST ia 2ae I113.1corp.)

dispositionem vocat Philosophus, justitiam metaphorice

(v) Interior justice applies to being before it applies to doing. Nevertheless the state

of justice presupposes the activity that is consonant with it, that is, the keeping

of the Commandments.

(vi) Human justice in the redemptive order of grace is incomplete and imperfect.

Man cannot in this world escape the consequences of original sin.

In the light of these observations we are able to assign the following meanings

to justice:

i. Quality of Justice: (a) divine (b) human

2. Condition of Justice: (a) divine (b) human (= OED s.v. truth,4)

3. Behaviour in accordance with Justice (= OED s.v. truth,9 b)

Strictly speaking we can distinguish between justice (I) and righteousness (2 and 3).

In practice, however, justice and righteousness are often used synonymously. This is

no doubt because of the tendency to define a habit in terms of its related activity;

hence for St Anselmjustitia est rectitudo (see ST 2a 2ae 58. I).

The most explicit statement of Christianjustice in medieval literature is to be found