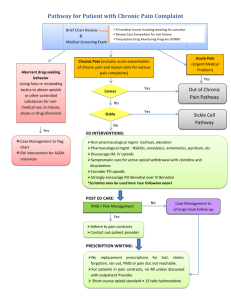

Acute Pain Assessment and Opioid Prescribing Protocol

advertisement