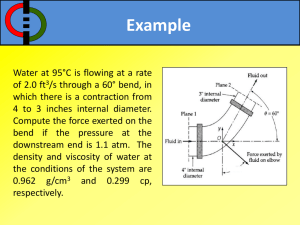

horseshoe bend - Fort Graphics

advertisement