Making Men in Sambia Gardens —Prehistory of Homosexuality II

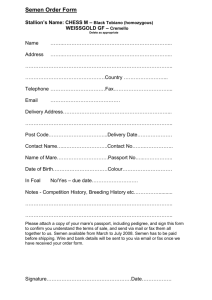

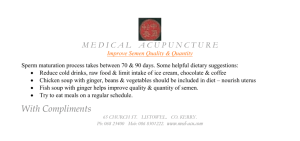

advertisement

U3A Course SBS 19/2006 “A World History of Homosexuality”; Presenter: Bob Hay Summary Session 8: Making Men in Sambia Gardens —Prehistory of Homosexuality II About 21,000 years ago the Earth’s climate took a nose-dive and mankind experienced the Last Ice Age. The cold drove humans in Europe south or east into “refugia”. Most of us are descended from those remote ancestors who lived out the Ice Age in northern Spain/Southern France where their magnificent paintings survive in the deep recesses of caves such as Altamira or Lascaux (NB: people do not appear to have lived in the caves but used them for ritual purposes). Around 10,000 years ago the Ice began to retreat and the earth to warm up once more. Then, about 8,000 years ago the invention of agriculture (probably by women), pottery and the domestication of some species of animals revolutionized human life-styles. These innovations occurred more or less simultaneously in the Middle East, China, South America, the eastern seabord of the United States, and a region extending from Mexico into Central America. And, as archeologists have recently been surprised to discover, New Guinea where humans had been living from about 35,000 years ago. Until very recently, people still lived in a manner probably very similar to the way their ancestors did when they dicovered how to garden. Remember, we cannot directly compare cultures or extrapolate from the historical to the pre-historical, but we can at least see how people managed their lives with similar resources. Pigs and Gardens: Trees began to re-appear in the New Guinea uplands about 9,600 years ago, following revegetation after the Ice Age by shrubs and leafy plants. When they first started to garden is uncertain but indications are that New Guineans have been gardening for the last 7,000 years. They also invented pottery (and still have a rich ceramic tradition) and domesticated pigs. This pushes the date of their agricultural revolution back almost as far as the invention of agriculture in the Near East. The so-called “Sambia”, semen-eaters: A feature of the initiation of boys into manhood common in Melanesia is “ritual insemination”, that is the putting into the boys’ bodies the semen of older youths or men, a practice which is believed essential to the proper growth of the boys into manhood. Of course, this practice was also found among many Murrayian Aboriginal societies in tribal Australia, and in Ancient Greece. The best-known of the Papua-New Guinea societies which practise this form of initiation are the so-called “Sambia”, a group of people who live in the South-Eastern Highlands. This was not their true name: the anthropologist who studied them, Gilbert Herdt, and whose book (and BBC documentary) called “Guardians of the Flutes”1 has made them famous, took pains to hide their true identity and location. Herdt lived among the Sambia from 1974-1976, during 1 Gilbert Herdt: Guardians of the Flutes, Volume 1: Idioms of Masculinity. University of Chicago Press, 1981, 1994 Preceding the book was Herdt’s 1977 PhD Dissertation The Individual in Sambia Male Initiation, Australian National University, Canberra. 1 which time these initiations were still carried out; by now, however, they are extinct, vanished under the flood of Christian missionary zeal and white fella cargo. The Sambia lived in small villages in a highly forested area on the edge of the Highlands. These villages were organised on a patrilineal basis without strong leaders or other social hierachical structures. Marriages were arranged either by peaceful exchange within the tribe or by “bride capture” from enemy villages. In the first, a pattern of cross-cousin marriage was favoured with girls from villages which were allies and the people welded together by kinship ties. On the other hand, the second method, Herdt argued, lead to the remarkable paranoia which existed between men and women in Sambia society. Among the Sambia, the division between the sexes was extreme and the male initiation rituals served to preserve this. This meant not only that there would have been no room in Smabia society for love and romance in marriage, at least until the man and women had spent many years sharing their lives and trust could have grown between them. For much of the time, women remained Woman as Object, not so much a personality to her husband but the vehicle through which he had his children but who was also skilled in growing things in the garden. The Sambia had an extraordinary fear of a son’s ties to his mother — whose allegiances could well be to the enemy village from which she came — and for that reason, young boys, as young as 6 or 7, were taken to live in the men’s house. Strict avoidance protocols were then the rule, women being forced to use different paths through the bush than the men and sons forbidden to speak to their own mothers. For the next decade or so, the youths lived in exclusively male company, being gradually taught the men’s ritual secrets, including special diets and the secrets of the flutes which, until then they had never seen and believed were the voices of initiatory spirits but which were now revealed to them as musical instruments the men themselves played, and taught the ritual association between the flutes and the penis. Because the Sambia believed that males were born with a tiny, deficient tingu, they “filled” it as often as possible with semen obtained by fellating an older (post-pubescent) boy. Although they said they were nervous at first about this interchange, they believed the older boy was helping them grow into strong, virile men. As they looked at it, this was “sex work”, not “play, and as such, was subject to strict rules. The younger boy was always the fellator, the adolescent the fellated. The older boy stood, the younger boy knelt in front of him and the interchange was always in strict privacy. Around about 14-16, the youths changed status and now became the “batchelors” who donated their semen to help younger boys grow into strong men. Later, around 17-21, the youths were judged strong enough to marry, although they did not have vaginal intercourse with their wife for some time, during which they continued to donate semen to growing boys. Once they assumed the full status of marriage they ceased to donate semen, although Herdt claimed maybe 5% were “backsliders” and continued to seek out boys who would be grateful to fellate them.. 2