The British Association of Plastic Surgeons (2003) 56, 623–629

The fascial planes of the temple and face: an enbloc anatomical study and a plea for consistency

J.J. Accioli de Vasconcellosa, J.A. Brittob, D. Heninc, C. Vachera,d,*

a

Service de Chirurgie Maxillo-Faciale, Hopital Beaujon, AP-HP, 100 Bd du Général Leclerc, Clichy 92118,

France

b

Royal Free and University College Hospitals, London, UK

c

Service de’Anatomie Pathologique, Hopital Bichat, 56 Rue Henri Huchard, 75018 Paris, AP-HP, Paris.

Faculté Bichat, Université Paris VII, France

d

Faculté Bichat, Université Paris VII, Institut d’Anatomie de Paris, France

Received 20 January 2003; accepted 24 June 2003

KEYWORDS

Anatomy; Superficial

musculo-aponeurotic

system; Face; Temporal

region

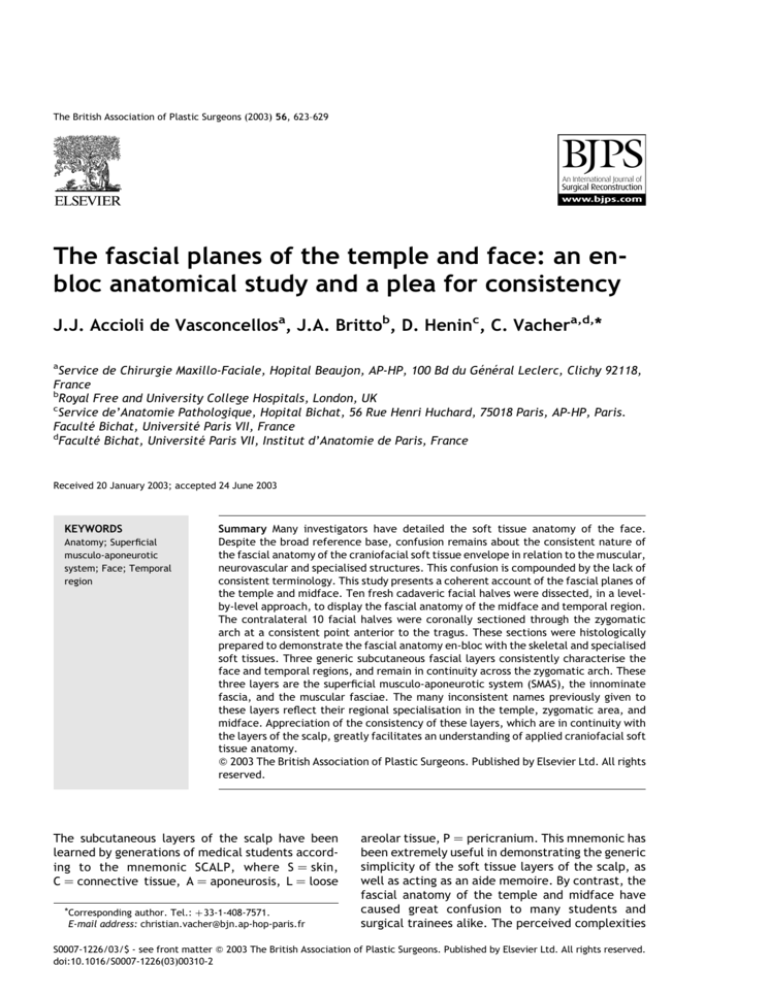

Summary Many investigators have detailed the soft tissue anatomy of the face.

Despite the broad reference base, confusion remains about the consistent nature of

the fascial anatomy of the craniofacial soft tissue envelope in relation to the muscular,

neurovascular and specialised structures. This confusion is compounded by the lack of

consistent terminology. This study presents a coherent account of the fascial planes of

the temple and midface. Ten fresh cadaveric facial halves were dissected, in a levelby-level approach, to display the fascial anatomy of the midface and temporal region.

The contralateral 10 facial halves were coronally sectioned through the zygomatic

arch at a consistent point anterior to the tragus. These sections were histologically

prepared to demonstrate the fascial anatomy en-bloc with the skeletal and specialised

soft tissues. Three generic subcutaneous fascial layers consistently characterise the

face and temporal regions, and remain in continuity across the zygomatic arch. These

three layers are the superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS), the innominate

fascia, and the muscular fasciae. The many inconsistent names previously given to

these layers reflect their regional specialisation in the temple, zygomatic area, and

midface. Appreciation of the consistency of these layers, which are in continuity with

the layers of the scalp, greatly facilitates an understanding of applied craniofacial soft

tissue anatomy.

Q 2003 The British Association of Plastic Surgeons. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights

reserved.

The subcutaneous layers of the scalp have been

learned by generations of medical students according to the mnemonic SCALP, where S ¼ skin,

C ¼ connective tissue, A ¼ aponeurosis, L ¼ loose

*Corresponding author. Tel.: þ33-1-408-7571.

E-mail address: christian.vacher@bjn.ap-hop-paris.fr

areolar tissue, P ¼ pericranium. This mnemonic has

been extremely useful in demonstrating the generic

simplicity of the soft tissue layers of the scalp, as

well as acting as an aide memoire. By contrast, the

fascial anatomy of the temple and midface have

caused great confusion to many students and

surgical trainees alike. The perceived complexities

S0007-1226/03/$ - see front matter Q 2003 The British Association of Plastic Surgeons. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00310-2

624

J.J. Accioli de Vasconcellos et al.

have been generated in part by the large number of

published anatomical and clinical studies, each

giving a separate nomenclature to the consistent

anatomical structure. An understanding of craniofacial soft tissue anatomy is, of course, a prerequisite to understanding both reconstructive and

aesthetic surgical procedures in this area. The

purpose of this report is to simplify the craniofacial

fascial layers and provide a generic account of the

fasciae of the temple and midface, within the

context of their regional specialisation around

skeletal, muscular, glandular and neurovascular

structures.

Materials and methods

Ten fresh cadaveric heads were used for this study.

Ten hemifacial specimens were subjected to a

level-by-level planar dissection of the subcutaneous fasciae from skin to bone or muscle. The

contralateral hemiface in each case was subjected

to excision of an 8 cm coronal strip of tissue, taken

at the junction of the posterior and middle thirds of

the zygomatic arch. Each strip was incised down to

temporalis muscle above and masseter muscle

below, thereby including a segment of the zygomatic arch. Each strip was fixed in 10% neutral

formalin and then subjected to coronal section.

Having been paraffin-embedded, these blocks were

cut at 5m and stained with haematoxylin, eosin and

saffron.

Results

The fascial anatomy of the temple

The generic fascial anatomy of the temple is

demonstrated in Fig. 1. The scalp and subcutaneous

fat and connective tissue have been reflected

anteriorly to show the layers of fasciae beneath.

The most superficial layer is the temporoparietal

fascia, which often demonstrates muscle fibres in

surgical dissections. This is the generic aponeurotic

fascia, and it continues cranially as the galea of the

scalp (SCALP), and anteriorly as the orbital and

most superficial part of the orbicularis oculi muscle.

The second layer is a loose fascial layer, highly

vascularised, and rather fragile, continuing cranially as the subgaleal fascia,1 or the alternatively

named ‘loose connective tissue’ layer of the

mnemonic SCALP. In generic terms, this second

layer of vascularised fascia is the innominate

fascia.2 The deepest layer is the tough, thick,

Fig. 1 The fascial layers of the temple. The aponeurotic

(temporoparietal fascia) layer is well defined and often

contains muscle fibres (A). The innominate layer is a loose

and areolar layer, but well defined as a fascial plane (L).

Temporalis muscle fascia (deep temporal fascia) is a

thick, white, plane, applied to the muscle (P). At the

level of the orbital roof, it divides into two planes, the

more superficial of which has been somewhat confusingly

called an ‘intermediate temporal fascia’ (Ramirez PRS

109, 329, 2002).

white temporalis muscle fascia, which continues

cranially as the cranial periosteum (SCALP), in

continuity at the temporal crest where temporalis

takes its cranial origin.

This anatomy, as demonstrated in planar dissection, is corroborated by en-bloc histological section

(Fig. 2). The five layers of the scalp, containing

three generic fascial layers, are all represented in

the temple. The temporoparietal fascia is the

aponeurotic layer. Beneath this is the ‘loose

connective tissue’ layer, or innominate fascia, and

in histological section it retains its multilaminate or

‘loose areolar’ structure as in the SCALP. It is highly

vascularised and not merely an avascular subfascial

space as has been previously suggested.3,4 The third

layer is the temporalis muscle (or deep temporal)

fascia. This fascia splits into a thin superficial layer

and a deeper, thicker and more fibrous layer, at the

level of the supraorbital margin. The superficial

lamina of the temporalis muscle fascia (deep

The fascial planes of the temple and face: an en-bloc anatomical study and a plea for consistency

Fig. 2 The coronal section shows the planar anatomy of

the temple. The SMAS layer is a single subcutaneous layer

(A). The innominate layer is a multilaminate, highly

vascularised structure, and this explains the ‘loose,

areolar’ description of the surgical anatomy (L). The

superficial fat pad (sfp) separates the innominate fascia

from the superficial lamina of the temporalis muscle

fascia (P), and is a surgical guide to the proximity of the

temporal branches of the facial nerve (VII n). Surgical

approaches to the zygomatic arch (ZmA) cleave the

superficial lamina of the temporalis muscle (T·m) fascia

and enter the intermediate temporal fat pad (ifp).

Masseter muscle (M·m) takes origin from the posterior

surface of the zygomatic arch periosteum. The fascia

overlying temporalis (deep temporal fascia) is a thick

defined fascia deep to and independent from the

zygomatic arch (P, deep limb).

temporal fascia) is continuous with the unified

temporalis muscle fascia above the level of the

orbit, and with pericranium above the level of the

temporal crest. It has been called the intermediate

temporal fascia,5 but in generic terms, the temporalis muscle fascia is the deepest layer of the

mnemonic SCALP. The splitting of the temporalis

muscle fascia into two laminae, separated by the

(‘middle’ or ‘intermediate’) temporal fat pad, in

functional terms allows the powerful contraction of

temporalis muscle to be dissociated from tethering

the temple.

The histological appearance of the innominate

fascia of the temple is a potential source of

confusion in considering the generic anatomy of

the craniofacial fasciae. There appear to be

multiple laminae, enclosing vascular planes. In the

surgical approach, however, a single vascularised,

innominate fascia is dissected (Fig. 3). The innominate fascia, richly vascularised by branches of the

superficial temporal artery, can be raised as an

ultrathin fascial flap for eyelid or auricular cover6 or

as a free vascularised fascial bilayer transfer in the

coverage of exposed tendons.6 It is a delicate flap in

625

Fig. 3 (A and B) Planar, level-by-level dissections of the

fasciae of the temple. (A) The innominate fascia (L) is a

well-defined, vascularised surgical plane deep to the

temporoparietal fascia (A), which has vessels ramifying

on its superficial and deep surfaces. (B) The innominate

and temporoparietal fascial flaps raised as a pedicled

bilayer fascial flap (Bilayer F.f) to easily reach the eyelids

and auricle, protecting the frontal branch of the

superficial temporal artery (F.br STA). A possible third

layer, the superficial lamina of the temporalis muscle

fascia might be included in the flap, raised on the middle

temporal branch of the superficial temporal artery.

clinical use and should be raised with temporoparietal fascia in its caudal third to guard its blood

supply. This bilayer fascial flap is a different entity

from that described by several authors,3,7 – 9 which

consists of a bilayer of the superficial lamina of the

temporalis muscle fascia, vascularised by the

middle temporal branch of the superficial temporal

artery, and the innominate and temporoparietal

fasciae raised together on the ascending branch of

the superficial temporal artery. In theory, a multilayer fascial flap could be raised, containing the

three laminae as separate vascularised layers in

pedicled or free tissue transfer.10

626

Fig. 4 Two plates from different subject cadavers

showing that the aponeurotic and innominate fascial

layers cross the zygomatic arch without attachment to it.

The temporal branches of the facial nerve (VII) are deep

to the innominate fascia (L) at this level, and in the roof

of the superficial temporal fat pad (sfp). Safe surgical

approaches to the zygomatic arch from the temple should

ideally be in the subperiosteal plane, necessarily cleaving

the superficial lamina of the temporalis muscle fascia

(circled) and exposing the intermediate temporal fat pad

(ifp). (ZMA—zygomatic arch; M·m—masseter muscle; ifp—

intermediate fat pad; A—SMAS layer; P—pericranial,

temporalis muscle (deep temporal) fascial layer).

The fascial anatomy across the zygomatic

arch

En-bloc histological section across the zygomatic

arch indicates that the generic structure of the

craniofacial fascial envelope is maintained (Fig. 4).

The temporoparietal fascia crosses the arch as the

aponeurotic layer, deep to which is the loose

areolar innominate layer. Despite previous reports

to the contrary4,11 neither of these layers attaches

to the zygomatic arch periosteum, and both are in

continuity with the corresponding generic layers in

the temple. The frontal (temporal) branches of the

J.J. Accioli de Vasconcellos et al.

facial nerve lie immediately deep to the innominate

fascia, between this and the zygomatic arch

periosteum. This is entirely consistent with their

course from the substance of the parotid gland, to

eventually lie deep to the musculo-aponeurotic

layer, within which the majority of the associated

muscles are innervated by the VII nerve from their

deep surface. This plane is characterised by a

superficial temporal fat pad12 a ‘wafer-thin’13

entity separating the innominate fascia from the

zygomatic arch periosteum. In this context the fat

pad which lies between the superficial and deep

laminae of the temporalis muscle fasciae is the

‘middle’ or ‘intermediate’ fat pad. The deep

temporal fat pad, often described as enveloping

the temporalis tendon caudal to the zygomatic

arch, was not seen in histological cross-section. It

may be, that as this structure dives deeply below

the arch it was out of the plane of our coronal cut

samples. Alternatively, this deep temporal fat pad,

also described as a temporal extension of the

buccal fat pad14 may have descended out of the

plane of our study in these cadavers as a consequence of the midfacial descent of normal ageing.

The zygomatic arch periosteum is in continuity

with the superficial lamina of the temporalis muscle

(deep temporal) fascia, and is, in generic terms, the

deepest layer described by the mnemonic SCALP.

The deep lamina of the temporalis muscle fascia

(deep temporal fascia) remains intimately related

to the temporalis muscle as it passes deep to the

zygomatic arch, and does not attach to the arch

periosteum (in contrast to the findings of Anderson

and Lo15). Temporalis muscle contraction is thereby

unimpeded by attachment to the zygomatic arch.

The fascial anatomy of the midface

Caudal to the zygomatic arch, and overlying the

region of the parotid gland, the aponeurotic layer of

the midface is dissected as the superficial musculoaponeurotic layer (SMAS) (Fig. 5), originally

described by Mitz and Peyronie.16 This layer is

continuous cranially as the temporoparietal fascia

and galea, and caudally as the platysma. Deep to a

SMAS flap, a glistening innominate fascia can be

demonstrated as an independent layer, overlying

the parotid gland, and continuing anteriorly to

protect the parotid duct and branches of the facial

nerve deep to it. In the midface, the innominate

fascia is a single, thin sheet, and ‘plasters’ the

parotid duct and emerging branches of the VII nerve

deep to it in the mid-anterior cheek as the

dissection proceeds anteriorly. When this layer is

incised and raised, the parotid gland and duct are

released into the wound, and facial nerve branches

The fascial planes of the temple and face: an en-bloc anatomical study and a plea for consistency

Fig. 5 The superficial musculoaponeurotic system

(SMAS) in the face can be raised as an adipofascial flap

in the parotid area (SMAS) to leave a thin glistening

innominate fascia overlying the parotid. Unlike in the

temple, this layer is adherent and thin over underlying

structures (the parotid). The innominate fascia (IF)

remains intact anteriorly, overlying the parotid duct,

branches of the facial nerve and the transverse facial

artery. It peters out towards the lip.

can be dissected freely. The floor of this ‘space’ is

the masseteric fascia. The parotid duct gains the

mouth by winding around the anterior border of

masseter and traversing the buccal fat pad (Fig. 6).

In the midlateral cheek, the more proximal course

of the VII nerve branches are protected deep to a

SMAS flap by the innominate fascia and substance of

the parotid gland. Careful dissection of a SMAS flap

in this area leaves the innominate fascia intact over

the parotid gland.

The deepest fascial layer, continuing caudally

from the zygomatic arch periosteum, is the masseter muscle fascia, generically the same layer as

the temporalis muscle fascia, and the scalp

pericranium. This is demonstrated in histological

section (Fig. 7). The SMAS and innominate fascia,

now attenuated to a single layer, overly the

parotid, whereas the masseter muscle fascia

remains applied to the muscle and is deep to the

parotid gland and, more anteriorly, the parotid

627

Fig. 6 The innominate fascia (IF) as an intact layer has a

glistening light reflex in the sub SMAS plane. When this

layer is breached, the parotid duct (Pd) and facial nerve

branches are released into the wound. The floor of this

space is the masseteric muscle (Mm) fascia, and more

anteriorly, the buccal fat pad (BFP).

duct. The parotid gland is not enveloped by a single

fascial layer that splits around it, but is a

specialisation of regional anatomy that is accommodated within the generic structure of the

craniofacial fasciae.

Discussion

The aim of this article is to present a simplified

means of addressing a region of important surgical

anatomy that is often misunderstood, and frequently confused in the surgical literature. There

are three fascial layers in the craniofacial soft

tissue envelope (Fig. 8). The deepest layer is the

fasciae of temporalis and masseter, which is in

continuity with periosteum at the bony attachments of these muscles. In the temple, this fascia is

split and this facilitates the unimpeded powerful

contraction of temporalis muscle.

The intermediate layer is the innominate fascia,

which in the temple, may in future have a useful

628

Fig. 7 Two plates from independent cadaveric subjects

showing that the generic consistency of the fascial layers

of the craniofacial soft tissue envelope are maintained in

the midface. The SMAS (A) and innominate fasciae (L) are

thin layers overlying the parotid gland (PG) and cranially

continuous up over the zygomatic arch. The masseter

muscle (M·m) fascia (P) is deep to the parotid gland and

continuous with zygomatic arch periosteum (circled).

There is no separate ‘investing fascia’ of the parotid

gland. (VII—temporal branch of facial nerve).

surgical application as an ultrathin pedicled flap for

eyelid or auricular cover. We have noted in our

dissections that the blood supply of this fascia is

attenuated in its caudal aspect, and easily separable from its blood supply from branches of the

superficial temporal artery. We would agree with

Carstens and colleagues6 that the innominate

fascial flap should be dissected in its caudal few

centimetres with the temporoparietal– aponeurotic

layer for pedicle safety. There is also potential for a

combined innominate – temporoparietal fascial flap,

supplied by the ascending branch of the superficial

temporal artery, for use in free flap tendon cover of

the distal extremity to provide a vascularised

bilayer as a gliding surface and to support a skin

graft.

The innominate fascia is the roof of the potential

J.J. Accioli de Vasconcellos et al.

Fig. 8 Plate showing the generic consistency of the

craniofacial fascial envelope. The ‘A’ layer is the

superficial musculofascial layer and overlies the innominate (L) layer which is loose in the temple and adherent in

the midface. The ‘P’ layer is the periosteal layer and

continuous with the fasciae of the muscles which arise

from it. Regional anatomical functional specialisation

allows for splitting of the temporalis muscle fascia (P)

above the zygomatic arch. Interposition of the parotid

gland, regional blood supply, and facial nerve occurs

between the innominate and aponeurotic layers in the

midface. These layers are important reconstructive flap

options above the zygomatic arch, and important landmarks in aesthetic surgery below the zygomatic arch

(ifp—intermediate fat pad; sfp—superficial fat pad).

space, around the parotid, into which the branches

of the VII cranial nerve emerge from their course

within the parotid. Hence surgical procedures

raising SMAS flaps anteriorly to the parotid will

protect the VII nerve as long as the intact

innominate fascia is deep to the dissection plane.

However, the VII nerve branches eventually traverse the innominate fascia in their course to

innervate the muscles of the SMAS, the majority

of which receive innervation from their deep

surfaces. In the zygomatic region, the safest

surgical dissection plane to avoid temporal branch

damage is subperiosteal. Elevating the subperiosteal midface suspension plane in aesthetic or

reconstructive craniofacial surgery from a buccal

The fascial planes of the temple and face: an en-bloc anatomical study and a plea for consistency

approach safely brings the instrument over the

zygomatic arch subperiosteally. The more superficial, subinnominate fascial plane is gained by

cleaving the superficial lamina of the temporalis

muscle fascia from the zygomatic arch, above the

level crossed by the VII nerve. Gosain et al.17 argued

that the majority of the temporal branches of the

VII nerve cross the middle third of the zygomatic

arch. Taken with our observations, it would seem

that a postero-anterior surgical exposure of the

zygomatic arch in a subperiosteal plane, in combination with the coronal scalp flap would be the

safest approach in craniofacial surgical exposure

requiring access to the midface. Exposure of the

upper third of the craniofacial skeleton without

exposure of the zygomatic arch, would aim to

sweep VII nerve forward in a combined skin—

aponeurotic—innominate fascial flap, leaving the

pericranium-temporalis fascial layer available for

other adjunctive flaps as necessary.

The most superficial layer is the aponeurotic

layer in the subcutaneous plane. It is continuous

with the orbital part of the orbicularis oculi

anteriorly, and the peripheral part of the orbicularis oris antero-inferiorly. Inferiorly it contains

platysma fibres, and superiorly, as the galea, it is in

a continuous sheet with the frontalis and occipitalis. In the midface, the zygomaticus muscles and

extrinsic lip elevators pass though it in reaching

cutaneous insertion. Above the zygomatic arch the

aponeurotic layer finds great use in reconstructive

surgery as the temporoparietal fascial flap, used as

a pedicled or free tissue transfer. This is also the

plane of extended galeal or ‘epicranial’ flaps18 and

these flaps may be pedicled on a variety of available

scalp vessels. Below the zygomatic arch, the

aponeurotic plane finds great use in aesthetic

surgery, as a means of suspending the skin of the

face and neck, and the relative benefits of its use

remain the subject of hot debate amongst aesthetic

surgeons.19

References

1. Tolhurst DE, Carstens MH, Greco RJ, Hurwitz DJ. The surgical

anatomy of the scalp. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;87:603—12.

629

2. Casanova R, Cavalcante D, Grotting JC, Vasconez LO,

Psillakis JM. Anatomic basis for vascularized outer-table

calvarial bone flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986;78:300—8.

3. Abul-Hassan HS, Von Drasek Asher G, Acland RD. Surgical

anatomy and blood supply of the fascial layer of the

temporal region. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986;77:17—28.

4. Heinrichs HL, Kaidi AA. Subperiosteal face lift: a 200 case, 4year review. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:843—55.

5. Ramirez OM. Three-dimensional endoscopic midface

enhancement: a personal quest for the ideal cheek

rejunevation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;109:329—40.

6. Carstens MH, Greco RJ, Hurwitz DJ, Tolhurst DE. Clinical

applications of the subgaleal fascia. Plast Reconstr Surg

1991;87:615—26.

7. Upton J, Baker TM, Shoen SL, Wolfort F. Fascial flap

coverage of Achilles tendon defects. Plast Reconstr Surg

1995;95:1056—61.

8. Biswas G, Lohani I, Chari PS. The sandwich temporoparietal

free fascial flap for tendon gliding. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;

108:1639—45.

9. Hirase Y, Kojima T, Bang HH. Double-layered free temporal

fascia flap as a two-layered tendon gliding surface. Plast

Reconstr Surg 1991;88:707—12.

10. Tellioglu AT, Tekdemir I, Erdemli EA, Tuccar E, Ulusoy G.

Temperoparietal fascia: an anatomic and histoligic reinvestigation with new potential clinical implications. Plast

Reconstr Surg 2000;105:40—5

11. Gosain AK, Yousif NJ, Madiedo G, Larson DL, Matloub HS,

Sanger JR. Surgical anatomy of the SMAS: a reinvestigation.

Plast Reconstr Surg 1993;92:1254—63.

12. Stuzin JM, Wagstrom L, Kawamoto HK, Wolfe SA. Anatomy of

the frontal branch of the facial nerve: the significance of the

temporal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989;83:265—71.

13. Moss CJ, Mendelson BC, Taylor GI. Surgical anatomy of the

ligamentous attachments in the temple and periorbital

regions. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105:1475—90.

14. Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, Wang JQ, Liu ZF. Anatomical

structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations.

Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;109:2509—18.

15. Anderson RD, Lo MW. Endoscopic malar/midface suspension

procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:2196—208.

16. Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic

system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr

Surg 1976;58:80—8.

17. Gosain AK, Sewall SR, Yousif NJ. The temporal branch of the

facial nerve: how reliably can we predict its path? Plast

Reconstr Surg 1997;99:1224—33.

18. Montandon D, Gumener R, Pittet B. The sandwich epicranial

flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;97:302—12.

19. Jones BM. Face lifting: an initial eight year experience. Br J

Plast Surg 1995;48:203—11.