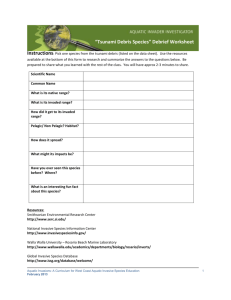

USEPA: Effects of Climate Change on Aquatic Invasive Species and

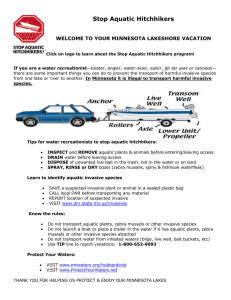

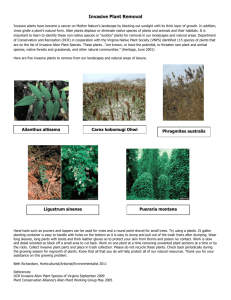

advertisement