Complete Lo Res Version

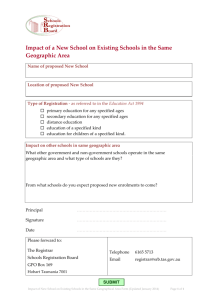

advertisement