From Objects to Words

advertisement

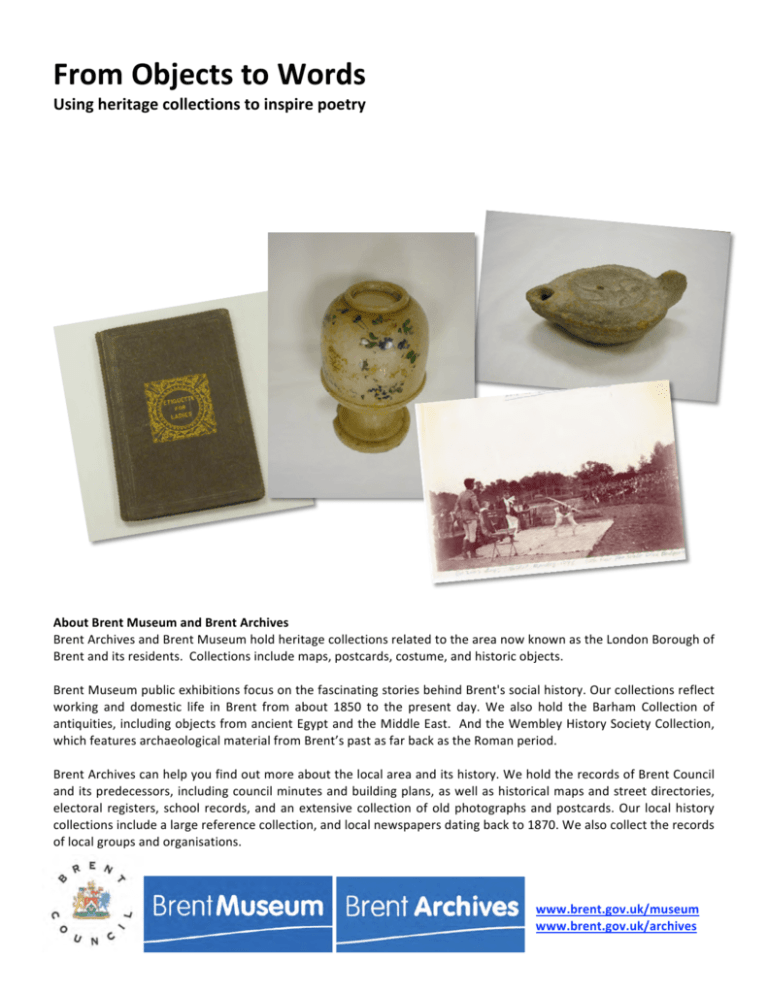

From Objects to Words Using heritage collections to inspire poetry About Brent Museum and Brent Archives Brent Archives and Brent Museum hold heritage collections related to the area now known as the London Borough of Brent and its residents. Collections include maps, postcards, costume, and historic objects. Brent Museum public exhibitions focus on the fascinating stories behind Brent's social history. Our collections reflect working and domestic life in Brent from about 1850 to the present day. We also hold the Barham Collection of antiquities, including objects from ancient Egypt and the Middle East. And the Wembley History Society Collection, which features archaeological material from Brent’s past as far back as the Roman period. Brent Archives can help you find out more about the local area and its history. We hold the records of Brent Council and its predecessors, including council minutes and building plans, as well as historical maps and street directories, electoral registers, school records, and an extensive collection of old photographs and postcards. Our local history collections include a large reference collection, and local newspapers dating back to 1870. We also collect the records of local groups and organisations. www.brent.gov.uk/museum www.brent.gov.uk/archives About this resource Poetry is a great way to creatively engage young people with a range of subjects including History, Citizenship, and English. It allows students to make personal responses to material and themes, exploring them in a way that combines their individual and social knowledge, with more formal knowledge gained from study of curriculum subjects. Developing and planning ideas and writing poems also builds confidence in literacy skills and communication. This resource pack includes ideas for activities and facsimiles of objects and images from the Brent Museum and Brent Archives collections. The exercises are designed to help students understand the basics of writing poetry. They can be used progressively over a number of sessions or as part of a planned Poetry Day. Brent Museum also offers a half‐day poetry workshop, which utilises gallery displays and original objects. For more information on this and all our workshops contact: museum@brent.gov.uk Notes for session leaders Where possible, take part in the exercises and share your work with the group. This is a great way to connect with your students and build trust within the group. Only read poems with the writer’s permission. Over time, performing their work in front of others should help young people grow in confidence. My real name is . . . Materials: Handout 1, pens/pencils, labels Time: 10‐15 min The following is inspired by Susan G. Wooldridge’s poem, ‘Our Real Names’ (Poemcrazy, 1996). The idea behind the poem is that our real names aren't necessarily the ones on our birth certificate; rather they are made up of our passions, our fears, our wildest dreams. Pass out Handout 1. Ask the group to think about how they feel, what they think about their lives, and what words they would use to describe themselves. Give them a few minutes to fill in the handout and ask them to read their poems aloud. My real name is __________ Yesterday my name was _______ Today my name is __________ Tomorrow my name will be ___________ In my dream my name was _________________ My friend (father, mother, brother, etc) thinks my name is ________________ With groups working for the first time together, ask participants to write their name on a label, either their ‘real’ name or the name they would like to be known by during the session. From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 1 of 8 What is poetry? Materials: Whiteboard / flip chart and pens Time: 15‐20 min Having warmed up in the previous exercise, discuss as a group the various answers to the question ‘What is Poetry?’ Explore the ways that young people receive and send information (telephone conversations, text messages, arguing). Look at the ways they use words in everyday life and emphasise that these are words and phrases they can use when writing poetry. Some ideas to discuss: ‐ Poetry is a form of communication, a way of sending a message, a way of getting a message across. ‐ It is a form of literature. ‐ There is no one type of poetry; it includes song lyrics, ballads, nursery rhymes... ‐ Poetry can be a collection of words or phrases that get you thinking. ‐ Any form of spoken or written words can be used poetically. ‐ A poem doesn’t have to tell a story; it could be a snippet; you don’t have to explain who you are or where the poem is going, you don’t have to construct a character, be logical or be chronological. ‐ An expression of emotions in an imaginative and beautiful way How do we convey meaning in a poem? Build on the first part of the discussion to explore ways poetry can be used to express and communicate ideas, emotions, or information. In poetry you can convey meaning through: ‐ Words ‐ each word carries meaning and can portray different things / ideas/ emotions depending on the context. ‐ Repetition ‐ if you repeat words, phrases, or sounds you imply and emphasize meaning. For example, in Tennyson’s ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ the poet both implies and emphasizes the dangers: ‘Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them, Cannon behind them, ...’ ‐ Framing the poem ‐ also known ‘circular structure’, this technique uses the same word or line at the beginning and at the end of a poem or verse to highlight the core message / emotion. For example in ‘Jenny Kissed Me’ by Leigh Hunt: ‘Jenny kissed me when we met, ... Time, you thief, who love to get Sweets into your list, put that in! ... Say I'm growing old, but add, Jenny kissed me.’ ‐ Punctuation ‐ creating pauses, slowing the words down or speeding the lines up. ‐ Through sounds ‐ where it is the sound of the word rather than it’s meaning that is important. From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 2 of 8 Rhyme/Rhythm/Free verse Materials: Handout 2 Time: 10‐15 min Use the poems in Handout 2 to discuss the ideas of rhyme and rhythm: Rhyme (repetition of the same sound), rhythm (the beat) and free verse (lines with no prescribed pattern or structure; the absence of rhyme or rhythm) are the key techniques that convey meaning through sound in poetry. The sound of a word is composed of the syllables in it. The number of syllables in a word is roughly the same as how many times the shape of your mouth changes when saying it. This means that every word is made up of a number of sounds/syllables and each of those sounds can have its own rhyme. So cat can rhyme with hat (as in ‘the cat in the hat’) but it can also rhyme with catch (as in ‘catch the cat quickly’). Sounds at the start of a word, in the middle (e.g. bubble and trouble), and at the end of a word can be rhymes. Formal, classic poetry follows strict rhyming structure: Sonnets ‐ are 14 line poems that usually have ten syllables in each line. The rhymes vary, for example Shakespeare uses the scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG in Sonnet 116: Let me not to the marriage of true minds A Admit impediments. Love is not love B Which alters when it alteration finds, A Or bends with the remover to remove: B O, no! it is an ever‐fixed mark, C That looks on tempests and is never shaken; D It is the star to every wandering bark, C Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken. D Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks E Within his bending sickle's compass come; F Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, E But bears it out even to the edge of doom. F If this be error and upon me proved, G I never writ, nor no man ever loved. G It can, however, be difficult to hear the rhythm in the sonnet. The stress placed on particular syllables and their arrangement in lines creates the rhythm of a poem: Limericks ‐ are humorous poems that have 5 lines and follow the scheme AABBA. The following is by Edward Lear: There was an Old Man with a beard, A Who said, 'It is just as I feared! A Two Owls and a Hen, B Four Larks and a Wren, B Have all built their nests in my beard!' A The rhythm – here fast and flowing – adds to the sense of the poem as light and fun, independent of the actual words. From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 3 of 8 If you have time, here is another limerick, written by Bruce Lansky, where the rhythm is analysed. Lines 1, 2 and 5 have three strong downbeats and the final syllables rhyme. Lines 3 and 4 have two strong downbeats and rhyme: There was an old man from Peru, (A) da DUM da da DUM da da DUM (3 DUMS) who dreamed he was eating his shoe. (A) da DUM da da DUM da da DUM (3 DUMS) He awoke in the night da DUM da da DUM (B) (2 DUMS) with a terrible fright, da da DUM da da DUM (B) (2 DUMS) and found out that it was quite true. (A) da DUM da da DUM da da DUM (3 DUMS) But a poem needs neither rhythm nor rhyme to be a poem. The arrangement / structure of the verses provide the lyricism/poetry: ‘This is just to say’, by William Carlos Williams, is an example of this free verse. I have eaten and which Forgive me the plums you were probably they were delicious that were in saving so sweet the icebox for breakfast and so cold From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 4 of 8 Describing an object Materials: Object images, notebooks, pens/pencils Time: 20‐25 min Use the images of objects from the museum collection. Ask everyone in the group to choose and object and read the information about it. Next read the following questions aloud and ask the group to write down the answers for their chosen object. They do not need to answer all of the questions. Encourage them to write single‐word answers, the first ideas that come to mind. ⋅ What is it? ⋅ What was it used for? ⋅ What colour is it? ⋅ What is it made from? ⋅ Who might have used it? ⋅ Where might it have been used? ⋅ How often was it used? ⋅ Can you think of anything we might use like this today? ⋅ What do you think it was it worth to its owner? ⋅ What is its value for you? ⋅ How old is it? ⋅ What condition is it in? ⋅ Does it look the same now as when it was made? ⋅ If it is worn or damaged, how and why did it get like that? Ask them to note down any other words that they thought of when looking at the object. These words are literal, giving a basic description. Poetry works by giving a more imaginative (‘figurative’) description. Ask the group to choose three of their words and use each one to develop a line of poetry. For example, here are some words that came to mind when looking at the object above, a flat iron c. 1870‐1914 (Brent Museum Collection, 1996.56.7): Iron, press clothes, flat, fold, brown, rusty, metal, women, clean, heat, sweat, dry, home, tool, work, families, daily use, now plastic and electricity, vapour, steam, common, hundred years old, broken, useless, door wedge. With these words the following lines were created: Rusty, tired tool Well‐used by weary women Busy, steam, sweat Beating flat the family’s folds ‐ Words are used imaginatively; an iron can’t real feel ‘tired’ ‐ Punctuation slows the rhythm of the first and third lines, suggesting someone doing a difficult job ‐ Rhyme is created by the repetition of letter sounds; well‐used by weary women (alliteration) Read some of the lines the group have written and discuss which are the strongest lines and why. From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 5 of 8 Simile & comparison Materials: Handouts 3 & 4, container for cutout words, notebooks, pens/pencils. Time: 15‐20 min The simplest way to describe things is to use adverbs and adjectives: ‐ Adverbs describe verbs or how something is done: e.g. slowly, happily, suddenly. ‐ Adjectives describe nouns: e.g. yellow, small, easy, loud. For example, small rusty iron. A poetic way to use words is to use more complex descriptions to create strong images. A simile suggests a thing is like something different. For example, your smile is like sunshine (the smile and the sunshine are not really similar.) A comparison suggests a thing is like something similar. For example, your smile is like the Mona Lisa’s smile Use Handout 3 to discuss simile and comparison; William Wordsworth’s poem, Daffodils, includes one of the best‐ known lines of poetry, which is also a simile. Use Handout 4 – adding extra words if you choose – to prepare a bag of words. Ask the group to each choose a word and then use it in a line to describe the object they previously chose: Object Word Line Iron Sand The iron glides like a snake over the sand This can be repeated several times. Then ask the group to pick two words and describe their object, in a single or a pair of lines. The words can be used as inspiration, so suggest flexibility with the chosen words, for example a student could use synonyms (words that have the same meaning or nearly) or antonyms (words that have opposite meanings). Personification & metaphor Materials: Handout 5 Time: 10 min Poetry allows writers to be very imaginative. For example, metaphor uses the description of something very different to convey an intended meaning. In ‘I Feel Like Dying’, L’il Wayne writes: I can mingle with the stars, and throw a party on Mars; I am a prisoner locked up behind Xanax bars. By describing the prisoner behind bars, the poet conveys his unhappiness. The prison is a metaphor for depression. (Note: He doesn’t write ‘my depression is like a prison’, which is a simile. A metaphor is an indirect comparison.) From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 6 of 8 In the metaphor above, the writer gave his depression the qualities of a prison, extending the metaphor by describing the bars as made of Xanax, a drug prescribed for anxiety. Poets use personification when they want to give human qualities to an object, an animal or an abstract idea; they give them a voice to speak for themselves. It looks at ideas from an alternative perspective. Riddles can be good examples of the use of personification. These are from ‘The Lord of the Rings’ by J.R.R. Tolkien (Handout 5). See if anyone in the group can work out the answer. Voiceless it cries, Wingless flutters, Toothless bites, Mouthless mutters. "Wind" This thing all things devours: Birds, beasts, trees, flowers; Gnaws iron, bites steel; Grinds hard stones to meal; Slays king, ruins town, And beats high mountains down. "Time" Writing a letter / The object’s response Materials: Object images, notebooks, pens/pencils Time: 25‐30 min Using the images, ask everyone to choose a different object to write a letter to. Thinking about what it could be like to be an ancient artefact or antique, they might ask the object what it feels like to be observed, to be inside a glass case, to be ignored, to be held, or what it thinks/feels about all the time it has experienced. Invite the group to share their letters. Explain the difference between prose and poetry. ‐ Poetry follows patterns that can be made by the structure, the rhythm or the rhyme. There is a relationship between words on the basis of sound as well as meaning. Generally it uses lines and stanzas. ‐ Examples of prose are letters, and essays. There is no decoration; the language is quite straightforward. It uses sentences and paragraphs. However, keep in mind that there is no clear‐cut division: there are also prose poems! Ask participants to swap their letters with the person sitting next to them and invite them to write a poem in response to the letter, imagining they were the object replying. What would your object say if it could talk? What were its most memorable journeys? Imagine the same object had been used over many years, passed from generation to generation; what memories and experiences would it have? You could consider how would the object might view the people looking at it and the expressions of contemplation / boredom / excitement / surprise. Think about the mood and atmosphere in the museum. Again ask if anyone wants to share their letter. From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 7 of 8 Labelling Materials: Handouts 6 & 7, notebooks, pens/pencils Time: 15‐20 min Revise what they have learnt so far. You might also use the Definitions resource to introduce other techniques used in writing poetry. For example, internal rhyme is a popular technique used by spoken word poets and rappers. In this, the rhyme is made within a single line. ‘My Melody’ by Rakim (Handout 6): My unusual style will confuse you a while If I were water, I'd flow in the Nile So many rhymes you won't have time to go for yours Just because of applause I have to pause Right after tonight is when I prepare To catch another sucker‐duck MC out there My strategy has to be tragedy, catastrophe And after this you'll call me your majesty... This style speeds us the rhythm of the poem, makes it more rapid – which is where the term ‘rapper’ originated, from ‘rapid spoken poetry’. Return to the idea of labels and ask the group to write a museum label for their object, in the form of a poem. Use the example in Handout 7 to see what a museum label typically contains (although they do not have to include all these details). Labels generally show the name of the object, the date it was produced, where it was produced, the material it is made of, how it was used and some historical context (what life was like at the time it was used and who it might have been used by). At the end of the exercise, ask if anyone wants to share their label. From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource Page 8 of 8 Handout 1 My real name is ____________________________________ Yesterday my name was _____________________________ Today my name is __________________________________ Tomorrow my name will be ___________________________ In my dream my name was ____________________________ My friend (father, mother, brother, etc) thinks my name is ____________________________ My real name is ____________________________________ Yesterday my name was _____________________________ Today my name is __________________________________ Tomorrow my name will be ___________________________ In my dream my name was ____________________________ My friend (father, mother, brother, etc) thinks my name is ____________________________ My real name is ____________________________________ Yesterday my name was _____________________________ Today my name is __________________________________ Tomorrow my name will be ___________________________ In my dream my name was ____________________________ My friend (father, mother, brother, etc) thinks my name is ____________________________ My real name is ____________________________________ Yesterday my name was _____________________________ Today my name is __________________________________ Tomorrow my name will be ___________________________ In my dream my name was ____________________________ My friend (father, mother, brother, etc) thinks my name is ____________________________ Handout 2 Sonnet 116 By William Shakespeare Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove: O, no! it is an ever‐fixed mark, That looks on tempests and is never shaken; It is the star to every wandering bark, Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken. Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle's compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved. There was an Old Man with a beard By Edward Lear There was an Old Man with a beard, Who said, 'It is just as I feared! Two Owls and a Hen, Four Larks and a Wren, Have all built their nests in my beard!' This is just to say By William Carlos Williams I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold Handout 3 Daffodils By William Wordsworth I wandered lonely as a cloud That floats on high o'er vales and hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host, of golden daffodils; Beside the lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze. Continuous as the stars that shine And twinkle on the milky way, They stretched in never‐ending line Along the margin of a bay: Ten thousand saw I at a glance, Tossing their heads in sprightly dance. The waves beside them danced; but they Out‐did the sparkling waves in glee: A poet could not but be gay, In such a jocund company: I gazed‐‐and gazed‐‐but little thought What wealth the show to me had brought: For oft, when on my couch I lie In vacant or in pensive mood, They flash upon that inward eye Which is the bliss of solitude; And then my heart with pleasure fills, And dances with the daffodils. Handout 4 stuffed Away pause click strength fear reflection battle Cycle preen justice idea care edge flummox Size whisper hate collective petal magenta sour Pleasure fuchsia magnolia courage result sphere surround Control lord tiny affection dollop dance admiral Ship silence exploratory blue anger malicious bouquet Future vessel life human welcome collaborate bridge Murmur tear steel destroy rain laughter connection Marriage balloon moon yes dream sigh death No door sky slattern labyrinth alcohol flattery Past puzzle metal coerce redemption smile love Acidic slaughter horde dragon space quibble organic Hewn present breathe harem embrace dust plastic Friendship crimson unscrupulous circus paradise fraction quiver Stumble late velvet voice passion obsession indigo magnify magnet cloud scope frost Geometry atone remove cold power sand jealousy Lens opposite mark warm tongue tropical wapping Mask curdle shake war poor home time Time polite star desperate gold familiar wave Shame subtle lips patriot silver foreign zigzag lime green helium compass riot flash united brief sensible heart perfume sin beast common joy tumbleweed alchemist grasshopper engrossed road Butterfly mellow error kingdom Hope ripe ice blood Sweet melody save tongue simple snake splash Regret mind delicious identity task glide innocence chemistry habit Handout 5 Riddles from ‘The Lord of the Rings’ By J.R.R. Tolkien Voiceless it cries, Wingless flutters, Toothless bites, Mouthless mutters. This thing all things devours: Birds, beasts, trees, flowers; Gnaws iron, bites steel; Grinds hard stones to meal; Slays king, ruins town, And beats high mountain down. Handout 6 My Melody By Rakim Turn up the bass, check out my melody, hand out a cigar I’m lettin knowledge be born, and my name’s the R A‐K‐I‐M not like the rest of them, I’m not on a list That’s what I’m sayin’, I drop science like a scientist My melody’s in a code, the very next episode Has the mic often distortin’, ready to explode I keep the mic in fahrenheit, freeze mc’s and make ‘em colder The listener’s system is kickin’ like solar As I memorize, advertise, like a poet Keep you goin’ when I’m flowin’, smooth enough, you know it But rough that’s why the middle of my story I tell EB Nobody beats the R, check out my melody... So what if I’m a microphone fiend addicted soon as I sing One of these for mc’s so they don’t have to scream I couldn’t wait to take the mic, flow into it to test Then let my melody play, and then the record suggest That I’m droppin’ bombs, but I stay peace and calm Any MC that disagree with me just wave your arm And I’ll break, when I’m through breakin’ I’ll leave you broke Drop the mic when I’m finished and watch it smoke So stand back, you wanna rap? All of that can wait I won’t push, I won’t beat around the bush I wanna break upon those who are not supposed to You might try but you can’t get close to Because I’m number one, competition is none I’m measured with the heat that’s made by sun Whether playin’ ball or bobbin in the hall I just writin’ my name in graffiti on the wall You shouldn’t have told me you said you control me So now a contest is what you owe me Pull out your money, pull out your cut Pull up a chair My name is Rakim Allah, and R & A stands for RA Switch it around, but still comes out R So easily will I E‐M‐C‐E‐E My repetition of words is check out my melody Some bass and treble is moist, scratchin’ and cuttin’ a voice And when it’s mine that’s when the rhyme is always choice I wouldn’t have came to set my name around the same weak shit Puttin’ blurs and slurs and words that don’t fit In a rhyme, why waste time on the microphone I take this more serious than just a poem Rockin’ party to party, backyard to yard Now tear it up, y’all, and bless the mic for the gods The rhyme is rugged, at the same time sharp I can swing off anything even a string of a harp Just turn it on and start rockin’, mind no introduction ‘Til I finish droppin’ science, no interruption When I approach I exercise like a coach Usin’ a melody and add numerous notes With the mic and the R‐A‐K‐I‐M It’s a task, like a match I will strike again Rhymes are poetically kept and alphabetically stepped Put in order to pursue with the momentum except I say one rhyme and I order a longer rhyme shorter A pause, but don’t stop the tape recorder I’m not a regular competitor, first rhyme editor Melody arranger, poet, etcetera Extra events, the grand finale like bonus I am the man they call the microphonist With wisdom which means wise words bein’ spoken Too many at one time watch the mic start smokin’ I came to express the rap I manifest Stand in my way and I’ll lead a words protest MCs that wanna be dissed they’re gonna Be dissed if they don’t get from in front‐a All they can go get is me a glass of Moet A hard time, sip your juice and watch a smooth poet I take 7 MCs put ‘em in a line And add 7 more brothas who think they can rhyme Well, it’ll take 7 more before I go for mine And that’s 21 mc’s ate up at the same time My unusual style will confuse you a while If I was water, I flow in the Nile So many rhymes you won’t have time to go for yours Just because of a cause I have to pause Right after tonight is when I prepare To catch another sucka duck mc out there Cos my strategy has to be tragedy, catastrophe And after this you’ll call me your majesty, my melody... Marley Marl synthesized it, I memorize it Eric B made a cut and advertised it My melody’s created for mc’s in the place Who try to listen cos I’m dissin’ to your face Take off your necklace, you try to detect my pace? Now you’re buggin’ over the top of my rhyme like bass The melody that I’m stylin’, smooth as a violin Rough enough to break New York from Long Island My wisdom is swift, no matter if My momentum is slow, MCs still stand stiff I’m genuine like leather, don’t try to be clever MCs you’ll beat the R, I’ll say oh never So Eric B cut it easily And check out my melody... Handout 7 Museum object label Object number: 1979.208 Title: Etiquette for Ladies Description: Dark brown cloth‐bound book, apprx 15cm high, with title 'ETIQUETTE FOR LADIES' in gold. The book included instructions on behaviour judged as appropriate for ladies in ‘polite society’. It included guidance on posture, on dress, and on how to speak to men in social situations. This edition was published in 1841, four years after the reign of Queen Victoria began. A similar book was published for men, revealing the concerns of people in a period when industrialization saw ‘ordinary’ people growing rich and wanting to move up in society, themes popular in the work of Charles Dickens. Publisher: Tilt & Bogue Production dating: 1841 Object name: Book Definitions Term Acrostic poem Alliteration Definition Uses the first letters of each line to spell a word, often the subject of the poem. Repetition of initial consonant sounds Assonance Repetition of the vowel within a word Ballad Tells a story or describes a person. Has a regular rhyme pattern. Blank verse Has meter but no rhyme Concrete poem It is written in a shape that adds meaning to the poem. Consonance Repeating the consonant within a word Couplet Two lines of poetry that usually rhyme. Dissonance Using clashing words to create a lack of harmony, usually to convey disharmony in the situation being described. Epic A long narrative poem centering on the deeds of a heroic figure or the fate of a nation. Figurative language Saying one thing and meaning another. The opposite of literal language. Free Verse Has no rhythm or rhyme. Haiku A 3‐line poem, usually about nature, with the syllable pattern: 5,7,5. Originally from Japan. Hyperbole An exaggeration made for effect. Image Language that creates a representation of an object or an experience. Limerick Fun poem that has five lines. Lines one, two and five have three strong downbeats and the ends rhyme. Lines three and four have two strong downbeats and rhyme. Line A unit of verse consisting of words in a single row. Metaphor Analogy or comparison where the author finds and expresses similarity between dissimilar things. Meter/rhythm/beat The pattern of stress/accent and non‐stress on syllables. Ode A meditation or celebration of a specific subject. Onomatopoeia The use of words or phrases that sound like the things to which they refer. Ex. Meow, clink, boom, mumble. Personification Used to give human qualities to an object,animal or idea. Rap Rapid rhythmic rhymes. Rhyme Repetition of the same sound. Rhythm Rhythm (or "measure") in writing is like the beat in music. In poetry, rhythm is achieved by the pattern of stress and non‐stress of individual words. The repetition of the pattern produces a rhythmic effect. Simile A comparison using ‘like’ or ‘as’. Stanza Sonnet Grouping lines within a poem. A 14‐line poem usually rhyming ABBAABBA, followed by two or three other rhymes in the remaining six lines. Symbol/ symbolism Anything that stands for or suggests something else. Verse A division of a poem. Example ‘Full fathom five...’ ‐ The Tempest, by William Shakespeare. ‘Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies’ ‐ To Autumn, by John Keats. Clock, brick. The test was a real killer. I have mountains of work to do. He is a machine. ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud…’ – Daffodils, by William Wordsworth Curriculum links This activity is closely linked to the English syllabus and meets the National Curriculum targets in the following ways: Promoting clear, coherent and accurate communication by reading and understanding a range of texts, and responding appropriately; through expressing complex ideas in speaking, writing and listening; by demonstrating flexibility and adapting to the demands of the different exercises. Encouraging pupils to show creativity by exploring a variety of starting points and making connections between ideas, experiences, texts and words; by experimenting with language, manipulating form, and reinterpreting ideas; by using imagination to create effects to surprise; by using creative approaches to answering questions, solving problems and developing ideas. Helps them develop their understanding of English literary heritage and modern writers; through comparing texts to explore ideas and engage with new ways in which culture develops; by understanding how spoken and written language evolve in response to changes in society and technology and how this process relates to identity and cultural diversity. Engaging them with ideas and texts, and helping them understand and respond to issues; by analysing and evaluating spoken and written language to appreciate how meaning is shaped; by examining the use of language and forms in a range of texts, challenging traditional ideas; and through expressing their own views independently. Follow on suggestions: Use the facsimiles of photographs and cuttings from the Brent Archives collection. Discuss what is happening in the images and then write a ballad style poem telling the story of what is happening in the image. Choose one of the Brent Museum objects. Use the facts provided and write an acrostic poem about the object. Choose either a person shown in one of the archive photographs or apply the technique of personification to one of the museum objects and write an epic poem about the adventures of that person / object. Links to useful websites: Poetry Archive http://www.poetryarchive.org Poetry Society http://www.poetrysociety.org.uk Shakespeare Sonnets http://www.shakespeares‐sonnets.com Teachit – Poetry Place http://www.teachit.co.uk/poetry.asp?CurrMenu=263 Young Poets Network http://www.youngpoetsnetwork.org.uk Winning Words http://www.winningwordspoetry.com From Objects to Words Brent Museum Poetry Resource End